- Sierra Leone adopted a presidential system in 1971.

- The parliament of Sierra Leone is unicameral. 124 members of whom 112 are directly elected. The remaining 12 seats are allocated to paramount chiefs; one from each of the 12 administrative districts. With the creation of two new districts in 2017, the number of directly elected members will increase to 132 in 2018. The current parliament is composed of members from the two dominant political parties, the All People’s Congress (APC) and the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP).

- Presidential and parliamentary elections will be held on 7 March 2018. To win in the first round a presidential candidate must secure 55% of the vote.

- Follow the vote on social media using the hashtags #SierraLeone2018 and #SaloneDecides

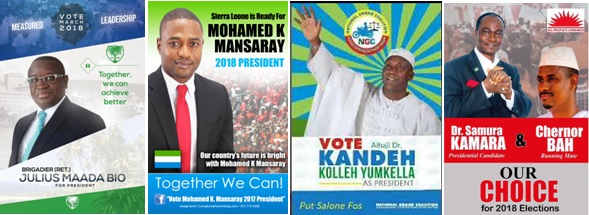

In March 2018 Sierra Leoneans will cast their votes to elect a new president and parliamentary representatives. After a decade at the helm, and having served the constitutionally mandated two terms in office, President Ernest Bai Koroma of the APC will step down. The three candidates vying to replace him are Samura Kamara (APC), Brigadier (Rtd.) Julius Maada Bio (SLPP) and Kandeh Yumkella from the newly created National Grand Coalition (NGC).

Credit: AYV News

Sierra Leone’s political history since independence in 1961 has been dominated by the APC and SLPP. The country is geographically and linguistically divided in its support for these two parties. In recent electoral history, Northern Temne- and Limba-speaking districts have predominantly supported the APC and southern Mende-speaking districts the SLPP. The two major “swing” districts in the country are Kono, in the east, and Western Area Rural and Urban (where Freetown, the capital, is located). Other political parties are broadly peripheral, although in 2007 a split in the SLPP that led to the creation of the People’s Movement for Democratic Change proved decisive in leading to victory for the APC. At present, parliament is composed entirely of politicians from the APC and SLPP.

Since independence, Sierra Leone has witnessed two transfers of power through the ballot box, but has also experienced military coups, one-party rule and sustained civil conflict. In 1967, Sir Albert Margai of the SLPP – brother of Sierra Leone’s first prime minister, Sir Milton Margai, who died in office in 1964 – lost a close-fought election to the APC and its leader Siaka Stevens. On the same day as he was sworn in, Stevens was removed by a bloodless military coup. Two further military coups followed, the second of which reinstated Stevens as prime minister in 1968. He was to lead the country for the next 17 years.

During his time in power Stevens oversaw the promulgation of two new constitutions. In 1971, Sierra Leone adopted a presidential system of government and in 1978 it officially became a one-party state. The latter was approved by 95% of voters in a referendum that was almost certainly manipulated. Elections continued to take place despite the repressive environment and the 1982 polls saw 52% of MPs and 17% of ministers lose their parliamentary seats, thereby showing that dissent and a degree of change were still possible. In 1985 Stevens stepped down, though he remained as head of the APC; his chosen successor, Joseph Momoh, was elected president.

1991 was a particularly significant year in Sierra Leonean politics: a new constitution was enacted that re-established a platform for multi-party democracy and civil war broke out. The conflict – which began in March when the Revolutionary United Front, with support from Charles Taylor in neighbouring Liberia, began a campaign to overthrow the Momoh government – was to last a decade, during which the political dispensation oscillated between military and civilian rule. Four years of the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC), headed by 25 year old Captain Valentine Strasser, was brought to an end in 1996 by some of the same military officers who had been part of the NPRC’s initial takeover in 1992 but who now supported a return to civilian rule. Current SLPP flagbearer Maada Bio was among them. Elections, described by David Harris, author of “Sierra Leone: A Political History”, as “unsurprisingly flawed given the conflict setting”, saw Ahmad Tejan Kabbah of the SLPP emerge victorious. However, by 1997 another military faction was in charge in the shape of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council. They were ousted after ten months by a regional intervention force – the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group – who reinstated Kabbah to return and complete his elected term.

At the end of the conflict in 2002, Kabbah was re-elected. Although there were accusations of inflated voter registration in SLPP areas, the victory was emphatic; Kabbah won 70% of the votes in the first round. Nevertheless, having won just 5% of the vote in 1996, the APC, led by a more youthful candidate in Ernest Bai Koroma, polled 22%. This performance went some way towards restoring Sierra Leone’s traditional two party dispensation and paved the way for the country’s second transfer of power at the ballot box in 2007, when Koroma defeated the SLPP’s Solomon Berewa in a run-off. Koroma secured a second term in 2012 by defeating Maada Bio (SLPP) in the first round. The SLPP challenged the validity of the results in court but was unsuccessful. In the 2012 polls, the APC also strengthened its position in parliament, gaining eight seats to hold 67 of the 112 available.

Enthusiasm for democracy in Sierra Leone remains high. Turnout for the three post-conflict elections, which have been substantially financed by international donors, averaged 81% despite logistical difficulties and the fact that nearly all elections in Sierra Leone have been accompanied by varying degrees of violence. The elections in March 2018 are likely to see a continuation of these features with many of the same political actors again present. Corruption and the state of the economy are likely to feature prominently during campaigning, but identity politics still remains a key driver of voting patterns. The winner will be confronted by an urgent (and familiar) need to deliver far higher, inclusive economic growth and mitigate some of the everyday hardships facing the majority of Sierra Leoneans.

Jamie Hitchen is a freelance analyst who has written extensively on governance in Sierra Leone. He tweets @jchitchen