Multi-party elections are a salient feature of Africa’s rapidly evolving political landscape. International support for elections is prioritised above all other strategies for consolidating democracy. The legacies of political reform are diverse, and variable. Technology, natural resource endowments, rising inequality, volatile food and fuel costs, and entrenched elites are influencing elections in ways few anticipated. These notes examine some essential traits of recent African elections, and consider their implications for future contests.

Democratic Africa

Africa is undergoing rapid political transition. Governments and politicians are confronted by voluble demands for greater transparency and accountability. The proliferation of mobile telecommunications has intensified scrutiny. Hegemonies – old and new – have adapted to fundamental changes in external relations and political rivalry.

African leaders confronted the uncertainties of the post-Cold War era with pragmatism and resilience. In the late 1980s and 1990s, economic liberalisation imposed by the World Bank and IMF coincided with dwindling external patronage. As governments looked to internal constituencies to underscore their legitimacy, political reform ensued. In 2012, only four countries in Africa lacked multi-party constitutions: Eritrea, Swaziland, Libya and Somalia.

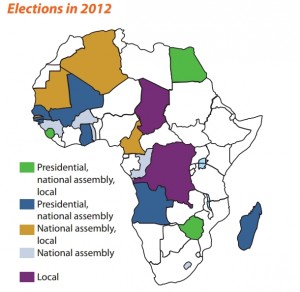

Multi-party elections are widely regarded as the benchmark for appraising the democratic credentials of African governments. In 1989, three African countries were labelled electoral democracies. By 2011, the number had risen to 18(1), and 15 countries held presidential, legislative and/or local government elections during the year. Twenty-three countries had polls scheduled for 2012 (2). Popular participation in elections is usually enthusiastic. In South Africa, voter turnout has exceeded 76% in all parliamentary contests since 1994 (3).

International donors intent on improving “governance” in Africa are closely involved in the funding, planning and monitoring of elections. Polls are costly: the 2011 elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) cost over US$700m, of which 37% was donor-funded (4). Support is underpinned by a belief that democracy will improve the accountability of governments – and development. But multi-party elections have produced diverse political outcomes and myriad unintended consequences, not all of which are progressive.

Voting and tactics

Substantial external funding for elections has recast political competition in Africa. Many multi-party elections involve the recycling of protagonists. In Nigeria, former military ruler Major General Muhammadu Buhari ran for the presidency in 2003, 2007 and 2011. Four potential candidates for the 2013 presidential elections in Kenya – Raila Odinga, Uhuru Kenyatta, William Ruto, and Kalonzo Musyoka – were stalwarts of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) which ruled unopposed for 39 years after independence. In most countries, new faces remain a rarity among those competing for the highest offices.

Political liberalisation has motivated opposition. Since 1991, 31 ruling parties or heads of state have been voted from office. In Ghana, the opposition has twice secured power peacefully since the first multi-party elections in 1992. But incumbent presidents win most African polls, prevailing over stifled or fragmented opposition. Twenty candidates attempted – unsuccessfully – to end the 26-year rule of President Paul Biya in Cameroon’s 2008 presidential election.

Ethnicity is commonly used to mobilise electoral support, intensifying and reinforcing political divisions. Nationwide support for the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) in the 2002 elections, which marked the end of a decade-long civil war, was short-lived. In 2007, the SLPP was predominantly supported by the Mende south and east of the country, while the Temne and Limba north and Krio community in the west rallied behind the All People’s Congress (APC). Ethnic or sectarian electoral loyalties more often reflect the dispensing and pursuit of patronage benefits than entrenched enmity.

Vote-buying is common, and effective. Cash – or favours – for votes constitutes a more immediate and tangible reward than promises to deliver public goods or reform policy. In Zambia, opposition leader Michael Sata resourcefully adopted “Don’t Kubeba” – “Don’t Tell” – as his campaign slogan for the 2011 presidential election, encouraging people to accept “gifts” from rival Movement for Multi-party Democracy politicians but not let that influence how they would vote. Sata won the presidency, and his Patriotic Front secured a majority in parliament.

“The problem of Africa in general and Uganda in particular is not the people but the leaders who want to overstay in power” – Yoweri Museveni, President of Uganda, 1986 (5)

Resounding victories at polls with voter turnouts above 90% are usually associated with countries governed by former liberation movements. President Paul Kagame polled 93% of Rwanda’s 2010 presidential vote. The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) led by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi won all but two of the 547 parliamentary seats in 2010. In Rwanda and Ethiopia, national elections have become formalities. The need for national reconstruction and accelerated development is cited as justification for consensus politics and the restriction of inter-party competition.

Violence

Accession to power through elections is the norm in Africa. In the 1960s and 1970s, three-quarters of African leaders were forced from office by coup d’état or assassinated (6). In the 2000s, there were eight military coups on the continent. The number of civil wars halved between 1992 and the mid-2000s. While elections have generally been more peaceable mechanisms for contesting power, politically motivated violence occurred in 60% of African elections in 1990-2008 (7).

Electoral violence is orchestrated by political elites to intimidate voters. “Youth wings” or party “task forces” are prominent exponents. In Zimbabwe, victory for the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) in the 2008 parliamentary election triggered an immediate and brutal response from President Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF). A campaign of beatings and targeted assassinations of MDC officials and supporters forced party leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, to withdraw from the presidential run-off vote.

Also Read: Old Tricks, Young Guns: Elections and Violence in Sierra Leone

Elections can exacerbate existing tensions. A recurrence of factional clashes in northern Nigeria followed Goodluck Jonathan’s victory in the 2011 presidential election. More than 800 people were killed in the fighting. Perceived consolidation of power by politicians from the predominantly Christian south, and enduring economic disparity between northern and southern states, fuelled the unrest. Clashes in Kenya’s Rift Valley following the 2007 elections reflected grievances among Kalenjin and Maasai over traditional lands allocated to Kikuyu in the 1970s by President Jomo Kenyatta.

The compulsion to retain public office – and susceptibility to resort to violence – is most pronounced in countries where state resources are the principal, or most easily accessible, repository of economic opportunity. Where elections are “winner takes all” contests, violence is a cheap and effective electoral device. The prevalence of electoral violence is a clear signal of the possibility of more widespread and protracted strife.

Growth, youth and protest

Democratic reforms have coincided with declarations of an economic renaissance in Africa, prompted by growth averaging 6% in the 2000s (8). Continental summaries and projections mask significant variations. Ghana’s GDP grew by 13.5% in 2011. In neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire, GDP contracted by 5.8% (9). Democratic reforms and economic growth have raised expectations among African electorates.

The economic – and democratic – potential of an emerging middle class in Africa is widely extolled. But per capita income in sub-Saharan Africa was lower in 2005 than in 1975. Inequality is rising and poverty levels remain stubbornly high. In Sierra Leone, while GDP growth averaged 5% a year in 2007-11, the purchasing power of low-income earners halved (10). No government in sub-Saharan Africa has yet created the conditions for sustainable and transformative agricultural or industrial development.

Scant progress was recorded in raising the quantity – or quality – of formal sector employment in Africa during the 2000s, despite democratic reforms. In South Africa, which boasts the continent’s largest and most diversified economy, 624,000 jobs were created during the 2000s. In 1997-98, 1.8m jobs were created in a single year. In 2012, a quarter of South Africa’s labour force – and more than half of 15-24 year olds – are unemployed (11).

The failure of elected governments to address deepening frustrations and hardships has fuelled popular discontent, from Swaziland to Senegal. In Malawi, 19 people died during protests at chronic fuel shortages, rising prices and high unemployment in July 2011. Uganda’s “walk-to-work” protests, orchestrated by opposition leader Kizza Besigye in response to a 50% surge in fuel prices between January and April 2011, were violently suppressed by the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM). Nationwide strikes brought the Nigerian economy to a standstill in January 2012 after the government removed subsidies and the price of fuel doubled.

Opposition leaders in Liberia, Uganda and the DRC positioned themselves as champions of the youth during elections in 2011. Almost three-quarters of Africa’s population are under the age of 30. With minimal education, skills or opportunities for employment, the young are acutely disadvantaged. As a sizeable and growing constituency that is often less bound by ethnic allegiances, young voters have become a prime focus of political party campaigns and rallies. While the dearth of economic opportunities suggests a need for caution about the imminent realisation of an economic “demographic dividend” in Africa, the young have become a leading force in electoral politics.

Institutions and process

The management of African elections has improved markedly, if unevenly. Public – and international – confidence in the independence and legitimacy of Ghana’s National Electoral Commission has been conducive to democratic consolidation in the country. The appointment of Professor Attahiru Jega to the Independent National Electoral Commission in Nigeria, and his insistence on the creation of a new voter register, enhanced perceptions of an institution and process commonly regarded with suspicion and mistrust. In 2007, Sierra Leone’s National Electoral Commission acted decisively by annulling votes from all 477 polling stations registering turnouts over 100%.

Where electoral management is weak, manipulation of polls persists. A deficient voter register, unfeasibly high turnouts and a host of other irregularities discredited the 2011 presidential election in DRC. In Uganda, the EU observer mission judged that “the power of incumbency was exercised to such an extent [in the 2011 elections] as to compromise severely the level playing field between competing candidates and political parties” (12).

Clear and agreed procedures for announcing – and contesting – election results are of paramount importance. A violent and prolonged stand-off followed the announcement of conflicting election results by the Independent Electoral Commission and the Constitutional Court in Côte d’Ivoire’s 2010 presidential election. In Liberia, the chairman of the National Electoral Commission was forced to resign after inadvertently signing a letter which confirmed that opposition candidate Winston Tubman had won the first round of the 2011 presidential election, contrary to the declared result. Despite Tubman’s insistence that voting irregularities proved that the election was rigged in favour of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and his boycott of the run-off vote, widespread conflict was averted.

“There have to be clear rules and people must accept the rules. This is very important in Africa because we have an attitude of winner takes all” – Kofi Annan, former UN Secretary-General (13)

Efforts to resolve electoral deadlocks by negotiation have been motivated by a desire to stop conflict – not uphold the integrity of the electoral process. In Kenya, interaction between members of the unity cabinet has been more collusive than collaborative, but the creation of a new constitution has raised hopes for a peaceful election in 2013. In Zimbabwe, the coalition between ZANU-PF and the MDC has been unequal and the joint Global Political Agreement remains largely unimplemented. A fair and peaceful poll in 2012 or 2013 is a remote prospect. Where intense grievances and rivalries persist in power-sharing arrangements, the faith of voters is undermined and subsequent elections are a potential catalyst for renewed instability.

By the book

Multi-party elections have fostered more widespread observance of formal rules and procedures. Institutions matter in ways they previously did not. Voters demand respect for national constitutions, and active participation in constitutional change. In 2006, Nigeria’s Senate rejected a bill for a constitutional amendment to enable President Olusegun Obasanjo to stand for a third term in office. Attempts to extend presidential term limits in Zambia and Malawi were also rebuffed. But constitutions – and state institutions – remain vulnerable to the concentration of power in African presidencies.

Presidents in Chad, Gabon, Guinea, Namibia, Uganda, Cameroon and Togo have extended their tenures through constitutional amendment. In Cameroon, the abolition of presidential term limits in 2008 enabled Paul Biya to gain a sixth consecutive term in office. President Museveni has eroded the oversight function of the Ugandan parliament, removing its power to vet ministerial appointments and investigate allegations of ministerial corruption and incompetence.

The military retains significant influence in most African countries. Close alliances – political and commercial – with civilian elites are commonplace. In Nigeria, “security” accounted for 19% of government expenditure in the 2012 budget – a sum equivalent to the allocations to education, health, power and agriculture combined. Before the death in office of President Malam Bacai Sanhá in January 2012, every one of Guinea-Bissau’s elected presidents had been removed by military coup d’état. In Niger, the military bolstered democracy by unseating President Mamadou Tandja in 2009. Tandja had dissolved the National Assembly and sought to abolish presidential term limits. Coup leader Lieutn-General Salou Djibo oversaw a constitutional referendum and the return of a civilian administration in March 2011.

Also Read: No Mr. President: Mediation and Military Intervention in the African Union

Some of Africa’s inter-governmental organisations have shown increasing readiness to support democratic processes. The African Union’s (AU) Peace and Security Council has consistently opposed illegitimate transfers of power. Six states had their membership of the AU suspended during the 2000s. Since 2005, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has also suspended and sanctioned coup leaders who refused to commit to hold elections. The inadequacy of penalties for non-adherence has compromised the efficacy of interventions, as have conflicting regional responses. Initiatives from the AU, Nigeria and ECOWAS, and South Africa to the crisis in Côte d’Ivoire following the 2010 election attested to intensifying competition for influence in sub-Saharan Africa – but also to a willingness to intervene that was unthinkable in the 1990s.

Vision 2020

Senegal’s 2012 presidential elections were hailed as a triumph for democracy in Africa. In the first round, 13 candidates opposed an octogenarian incumbent president, Abdoulaye Wade, pursuing a third term in office. Former prime minister Macky Sall defeated Wade in the second round by a substantial margin. Wade had consistently undermined state institutions and the progressive new constitution he introduced in 2001. He exhibited dynastic pretensions and a predilection for grandiose schemes – but accepted the election result. As neighbouring Mali’s democratically elected leader was simultaneously ousted by a military coup, Senegal’s pride in its democratic credentials was preserved.

African elections have assumed their own character and momentum during the 2000s – a decade of immense political transformation. Assertions that multi-party polls are merely a sop to Western donors and a foreign imposition are wide of the mark, and disingenuous. Elections have assumed a significance which political elites cannot ignore. The relevance of developments in North Africa and the Middle East since 2011 may be casually dismissed in public, but is inescapable. While elites will continue to adapt, and to manipulate electoral processes, social and economic realities will force reckonings with voters during – and in between – elections.

Profound social and economic developments will cause further radical changes in political processes and competition in Africa. Youth, joblessness, mobility, burgeoning urban populations and inequality are already key factors in African elections – and will become even more significant. Economic growth during the 2000s has not been shared by governments and elites. Even in countries which benefited substantially from high prices for their natural resources, investment in public goods, agricultural transformation and infrastructure has remained derisory. Sound policymaking – not elections – generates development and reduces poverty. But elections are an essential lever for improving the accountability and transparency of governments.

Effective policy is not the exclusive preserve of democratic government. So-called “competitive authoritarian” regimes in Africa have proved alluring to donors and investors alike, from East and West. Whether these regimes will succeed in emulating counterparts in Asia is uncertain. An over-emphasis on control and coercion and too little inducement would fail to produce the desired outcomes. Emerging alliances with China, Brazil, India and other rapidly developing states enable authoritarian regimes to stonewall demands – internal and external – for democratic reforms and political pluralism. In the 2000s, the balance of power in Africa altered as dramatically as the political landscape.

Expectations about elections must be realistic, in Africa as elsewhere. Elections are not a “silver bullet” for effecting immediate and positive political change. A poll deemed “free, fair and credible” by international observers does not automatically signify a thriving democracy. But the democratic genie will not be returned to the bottle in Africa – and the further consolidation of electoral processes and institutions is imperative.