Self-sufficiency in food production is the new mantra of donors and policymakers in Africa. But farmers, large and small, can be much more ambitious. Agriculture is the continent’s most neglected – and important – potential competitive advantage. It is Africa’s best answer to globalisation. Until farming is commercially viable, there will always be hunger in Africa.

Self-sufficiency in food production is the new mantra of donors and policymakers in Africa. But farmers, large and small, can be much more ambitious. Agriculture is the continent’s most neglected – and important – potential competitive advantage. It is Africa’s best answer to globalisation. Until farming is commercially viable, there will always be hunger in Africa.

By Mark Ashurst and Stephen Mbithi

Listen to the podcast of “Why Africa can make it big in agriculture”

[display_podcast]

A short walk from the Rwandan parliament, the Vision 2020 Snack Bar is a roadside eatery popular with Kigali’s office workers and taxi drivers. The café takes its name from Rwanda’s national development plan, drafted by the government of President Paul Kagame – a choice which belies more than mere patriotism. Food is critical to Africa’s prospects, and farming is the best hope for impoverished rural economies on which 70% of the continent’s poor depend. With more ambition, commercial agriculture would transform Africa’s balance of trade.

At a time of growing international concern about global food security, the example of Rwanda is instructive. For the first time in recent history, Rwanda produced as much food as it consumed in 2009. This is a formidable achievement – and, at times, controversial. Rwanda is Africa’s most densely populated country. Most smallholders occupy tiny plots of land, passed down and repeatedly sub-divided through the generations. In the land known as mille collines, or a thousand hills, their livelihood is freighted with larger significance. Ethnic categorisation of Hutus and Tutsis was made illegal in the wake of the genocide of 1994, but a vast majority of rural smallholders consider themselves to be Hutu. President Kagame’s administration knows that building food security for the rural population is the key to political stability, the foundation of Rwanda’s much admired recovery.

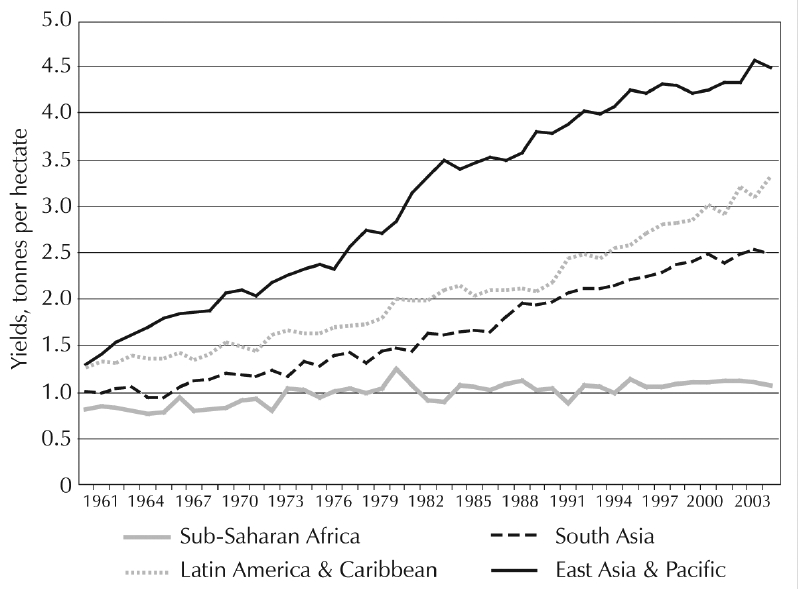

As in Rwanda, so too for much of Africa: improvements in agriculture are vital to the continent, and to the world. Worldwide, at least a billion people – one person in six – are hungry. By 2050, the global population is forecast to rise by a third. Africa’s population is forecast to double. Meanwhile, average cereal yields in Africa have shown no improvement since the 1960s – in contrast to steep rises in productivity throughout much of Asia. Over the same period, Africa has moved from being a net exporter to importing a quarter of its food. Rapid population growth, poor infrastructure and persistent under-investment have negated the benefits of new technology, improved seed varieties and growing international trade in food. In order to reverse this trend, new policies must unlock the potential for commercial agriculture.

The new fashion in development

Among donors, agriculture is once again the hot topic of international development. A gamut of international agencies – including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) chaired by former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan – have emphasised the need to improve productivity among African smallholders. But the policies devised by governments and donors imply a daunting lack of ambition. Worldwide, total production of food exceeds consumption. The know-how exists to keep pace with population growth, and the means to feed the planet are within reach – if only governments, and farmers, can find them.

A constant refrain among policymakers is that smallholders must become self-sufficient. “It is time for Africa to produce its own food and attain self-sufficiency in food production,” says Annan. Self-sufficiency is a reasonable goal, but as the key determinant of policy it is ambiguous – and timid. About two thirds of Africans depend on agriculture for their livelihoods, including a majority of those living below the poverty line. Many smallholders are, like city-dwellers, net purchasers of food. The rhetoric of self-sufficiency exhorts rural populations to grow more staple crops, rather than pressing for hard-headed policies to claim a larger share of the global trade in food.

Until agriculture is commercially viable, there will always be hunger in Africa

While the mantra of self-sufficiency is often misguided, the underlying rationale for helping smallholders is sound. Higher productivity means a better harvest for farmers. Better harvests should mean lower – and less volatile – prices. New technology has made it possible substantially to improve soil fertility and to cultivate drought-resistant strains of staple crops. Improved storage and better management of national reserves can reduce waste – in 2009, more than 40% of Kenya’s grain harvest spoiled in store. For aid officials keen to support measures which will reduce poverty, investing in agriculture can seem a deceptively simple proposition. Good intentions aside, the stakes are far higher than the narrow agenda of poverty reduction.

Agriculture is Africa’s most neglected – and important – potential competitive advantage in the global economy. For as long as Asia is the engine of the world’s manufacturing, and western countries dominate the pharmaceutical industry, Africans will continue to import their pots and pans, medicines and cars. Yet Africa’s potential as a cost-effective producer of food for export remains largely untapped, in spite of available land, improved technology and the low cost of labour. Although commercialisation of agriculture is often controversial, the imperative of building profitable agriculture in Africa has been evaded.

Being competitive

The patterns of global trade in food are changing fast. In recent years even China, long admired for its determined pursuit of self-sufficiency in food, has become a net importer of maize. For better and for worse, globalised commercial agriculture is coming to Africa. The reflex response has often been to bemoan the ‘land grab’ by multinational food groups and investors from Asian and Arab states, when a more practical reaction would be to devise strategies for more African participation in a burgeoning international food trade. External demand brings the prospect of economic growth and improved rural incomes. Agriculture must be Africa’s answer to globalisation – for large industrial farms and smallholders alike.

Whether or not this can be achieved is, above all, a matter of making the right decisions in government and for business. First, policymakers must separate agricultural ambitions and investment – cleanly, and unambiguously – from other measures to reduce poverty among rural populations in Africa. Both are absolutely necessary, but the rhetoric of agricultural self-sufficiency is a recipe for confusion. Food security is not the same as self-sufficiency among smallholders. These are distinct ideas, but routinely conflated. For example, although Dubai is a desert, its wealth ensures a stable supply of imported food. In Africa, food security is contingent on greater economic efficiency, especially in agriculture. Africa needs food security, not self-sufficiency in food.

The lesson is that growing enough food to feed the family is not the best policy for every farmer – as many arguments for self-sufficiency can imply. National food security is a legitimate priority for governments, but not an end in itself. The bigger picture is just that – bigger. Global demand for food is a strategic opportunity to re-balance the iniquities of world trade in Africa’s favour. While policymakers are surely correct to expect that rural populations should benefit from agricultural growth, the pursuit of self-sufficiency is not an effective tool to reduce poverty. Until agriculture is commercially viable, there will always be hunger in Africa.

No African leader needs to be told that the fate of rural livelihoods may determine his or her own. Food shortages are the dominant public concern in many developing countries – even more so since 2008, when soaring prices for staple crops sparked riots in parts of Africa, Asia and South America. The subsequent easing in commodity prices is unlikely to be permanent. Yet while new investment has picked up, the record of spending by African states is mixed. In 2003, African leaders adopted a Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP). Since then, only one country – Mali – has consistently met the CAADP target of spending 10 per cent of the national budget on agriculture.

A question of scale, and value

Being commercial means being competitive. In agriculture, commercial has become a short hand for ‘big’. Commercial farmers are generally assumed to be ‘largeholders’ – typically, the big estates in Egypt, Kenya, South Africa or Zimbabwe. This is wrong. In purely economic terms, medium-scale farms are the hardest pressed to generate returns on investment: they require mechanised farming, without scope for significant economies of scale. In contrast, smallholders who labour by hand can be competitive – provided they secure access to markets. Tens of thousands of smallholders, for example, can achieve massive economies of scale by coordinating their crops and harvests.

Plot size is a poor indicator of what is commercial or competitive. The proprietors of large-scale commercial farms often enjoy close ties to political elites, which bring a disproportionate share of state benefits such as subsidies, infrastructure or a favourable tax regime. While agri-business has become attractive to investors as a means to generate foreign exchange, smallholders often prove to be more diligent custodians of their land and ecology. In Kenya, smallholders have prospered in non-traditional markets by turning from staples to horticulture – a sector which has quadrupled in value since 1975. A better definition of ‘commercial’ would eschew any notion of size in favour of both being competitive and having access to markets.

Smallholders in particular must chart a difficult course between scale and value. In Rwanda, Vision 2020 includes a plan to agglomerate small plots into large, communally-owned rural ‘clusters’ to support intensive cultivation of staple crops. For others, a better strategy can be to diversify away from dependence on a single staple. In semi-arid areas of Zimbabwe, varieties of finger millet have proved more resistant to drought and better suited to long-term storage than maize. Foreign earnings from Kenyan flowers, fruit and vegetables in 2009 were about a billion US dollars, more than banking, tourism, telecoms or brewing.

The example of Kenya

Rural livelihoods around Mount Kenya have been transformed. While large commercial estates dominate production of roses, two thirds of Kenyan vegetables are grown by smallholders. Farmed by hand, with strict controls on the use of fertiliser and pesticides, smallholders’ green beans and sweet potato are premium crops – and of comparable quality to those cultivated by large-holders. Farmers typically earn six times more from horticulture than they would from growing maize. The extra money pays for school fees, medical care – and, of course, for food. For Kenyan vegetable growers, food security means money in the pocket of the farmer – not food in the granary.

A visitor driving from Nairobi towards Mount Kenya is struck first by the lush green of the landscape, in contrast to the dry red dust of the roads. The climate is favourable, but the ground requires extensive irrigation. A network of man-made canals, dating from the colonial period and extended in the 1980s, is maintained by financial contributions from local farmers who dig connecting ditches to their own plots. Smallholders supply weekly harvests to larger farms and businesses which package their crops for export. About 5% of horticultural output is exported, mostly to Europe, earning about 50% of the industry’s revenues.

Like any industry, the prospects for African horticulture depend on comparative advantage. Kenyan horticulture owes its success to a combination of location and organisation. Flowers, fruit and vegetables are perishable. In Africa, they are grown under the sun and farmed in the old-fashioned way – by hand. Sound infrastructure and regular flights to Kenya enable swift delivery to Europe, often in the holds of passenger aircraft – a fact ignored by European rivals who have campaigned, on dubious grounds, against the ‘carbon footprint’ of air-freighted fruit and vegetables.

Small farmers may be risk-averse but they are not hostile to innovation.

Not all the factors which have enabled the spectacular growth of Kenyan horticulture are replicable, but many are an example to policymakers elsewhere. Smallholders coordinate production within local groups, which in turn are highly integrated with exporters. Approved seeds and other inputs often are supplied by the exporters. A framework of ‘Private Voluntary Standards’ devised by European retailers is carefully followed by growers. Kenyan farmers comply with the strict requirements of the Global Partnership for Good Agriculture Practice (GlobalG.A.P), the internationally approved private standard for agriculture. Kenya is the only African country with a local system of standards – Kenya GAP –accredited by GlobalG.A.P.

In defence of ‘directed’ agriculture

Most smallholders are risk-averse. Many are wary of collective ownership and non-traditional crops. None will be convinced by policy statements. In Rwanda, critics of President Kagame’s reforms caution that at least some aspects of policy are coercive. Local administrators employed by the government in Kigali are tasked with ‘zoning’ and ‘mono-cropping’ and the resettlement of rural populations in new village ‘clusters’. In recent years, Rwanda’s policy has prompted comparisons with Ujamaa, President Julius Nyerere’s policy of villagisation and collective agriculture in Tanzania in the 1970s.

The circumstances of 21st century Rwanda are substantially different from those of Tanzania after independence – a difference which is to some extent disguised by the familiar rhetoric of self-sufficiency. Food security in Rwanda is a substantial achievement by the government, rather than an organised private sector. In contrast, Ujamaa triggered successive food crises and deepening dependence on food aid. A more apposite comparison is East Asia. President Kagame’s variant of state-directed agriculture recalls the post-war management of infant industries in Japan, Singapore and South Korea, where government technocrats decided policy and controlled capital investment. In that sense, Rwanda demonstrates a new and updated form of ‘directed’ agriculture in Africa.

Where directed agriculture fails, the consequences can be catastrophic. In Rwanda, the danger of famine would be compounded by the political risks of resistance among rural populations. To secure their compliance, smallholders receive subsidised seed and fertiliser from the government, and the promise, eventually, of a stake in larger co-operatives. Small farmers may be risk-averse but, contrary to some assumptions, they are invariably not hostile to innovation. Although few will be convinced by a seminar, most will be persuaded by the example of a neighbour who has prospered. In Kigali, policymakers have kept a close eye on Mount Kenya.

On closer inspection, Kenyan horticulture shares many characteristics of ‘directed’ agriculture – whether in Rwanda, or elsewhere. An emphasis on ‘bulking’ and uniformity of production is common to both countries. Large exporters arrange distribution of the best seed varieties, fertiliser and other inputs via farmers’ groups. Instead of following government diktat, smallholders follow the stringent demands of the export market. Kenya’s horticulture farmers have prospered because they reliably produce high quality vegetables to meet the short inventory lead times of European supermarkets. The key difference is that, because horticulture is not a staple food, Kenya’s dynamic private sector operates without interference from the government.

An African answer to globalisation

The opportunities for African agriculture in world trade are real, and demonstrable. Where food security is precarious, state direction of staple crops is inevitable in order to build up a national grain reserve. That is a different priority from the emphasis on self-sufficiency that has become familiar from AGRA and other donor agencies. Self-sufficiency implies growing enough to feed yourself – that is, to grow food for your own family. It is not the same as national food security, which requires access to a stable supply of food. More importantly, it obscures the crucial principle that agriculture must be competitive in local, or international, markets.

Many African ministers, buoyed by a spate of new investment and expressions of solidarity from Beijing, are fond of citing China’s state-sponsored capitalism as an alternative to development models proposed by western donors. Yet China’s Green Revolution, launched in 1978, followed a more nuanced trajectory than many of the ideas recently touted for Africa. To achieve self-sufficiency in grain, Beijing shifted production from ‘people’s communes’ to household farms, and opened state-controlled agricultural markets to private trade. Self-sufficiency in food brought political stability as a foundation for industry and manufacturing.

The root of poverty is lack of money – not a lack of food.

A Chinese-style industrial revolution will not happen in Africa without reliable power, infrastructure and effective regional integration. But a genuine Green Revolution for Africa in the 21st century is within the bounds of possibility. Three decades on, rising prosperity in the populous economies of China and India has increased demand for production of resource-intensive meat, adding to pressure on finite reserves of land and water – and driving demand for cattle feed. The global trade in agriculture is both an opportunity and a threat. For Africa to maximise the benefits and minimise the risks, the overriding priority is to improve skills and know-how.

The prospects for African agriculture hinge on producing crops which others want to buy. The most productive investment will be in locations where farmers, large and small, are able to integrate their systems in response to market demand. Where the efficiency and low costs of smallholders can be combined with the market access and quality controls of largeholders and exporters, Africa’s farmers can create a dynamic and market-led industry. For policymakers, the key working principle is to remember that the root of poverty is lack of money – not a lack of food.

COUNTERPOINTS

The Counterpoints series presents a critical account of defining ideas, in and about Africa. The scope is broad, from international development policy to popular perceptions of the continent.

Counterpoints address ‘Big Picture’ questions, without the constraints of prevailing opinion and orthodoxy. The arguments are forward-looking but not speculative, informed by the present yet concerned with the future.

In publishing this series, Africa Research Institute hopes to foster competing ideas, discussion and debate. The views expressed in Counterpoints are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of Africa Research Institute.