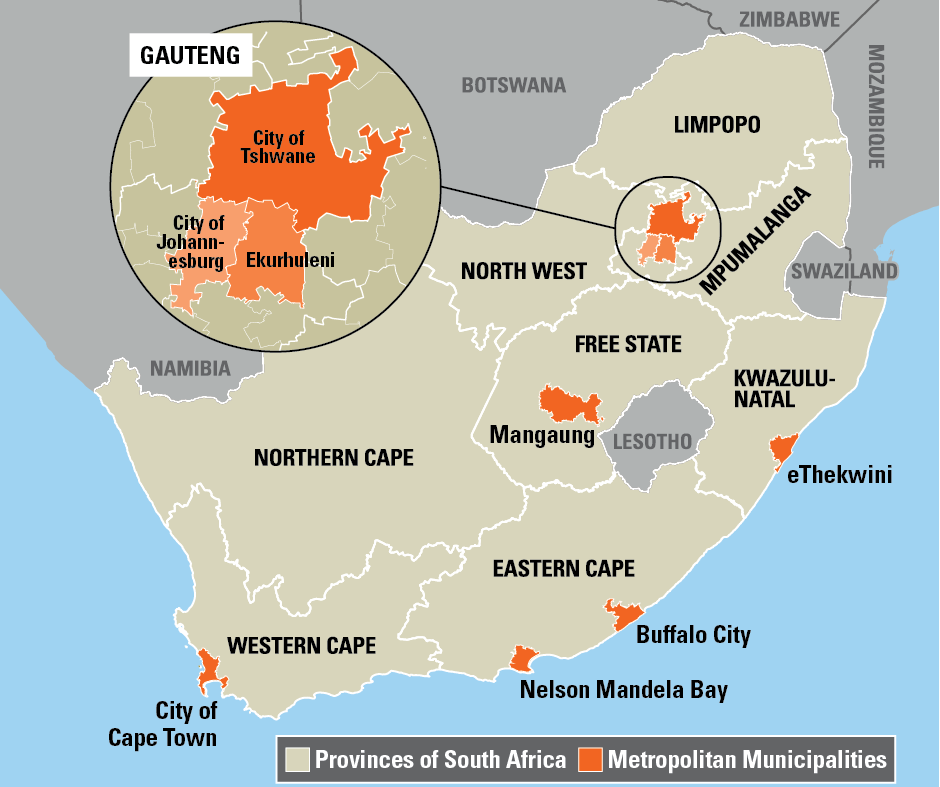

Municipal elections have had a brief and unremarkable history in post-apartheid South Africa. However, the polls on 3 August are expected to be the most fiercely contested of any to date. South Africa’s demography is changing rapidly and with it the political landscape. The eight largest city councils – known as metropolitan municipalities, or “metros” – are home to some 40% of the population, where the share of the vote held by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) is in decline.

Amid the clamour for votes, ANC infighting and heated rhetoric, little attention has been paid to the state of the country’s municipalities. Local governments are responsible for R250 billion of expenditure a year, equivalent to 8% of GDP.[1] Their impact on the daily lives of most citizens is far greater than that of the national administration. The ANC may well lose control of one or more of the seven metros it holds. In the absence of a clear winner, coalitions may be required to govern four of them. Yet, in pursuit of radically different electoral constituencies, the country’s three main political parties have adopted seemingly incompatible approaches to governance. This Briefing Note examines the backdrop to an election that is likely to be a watershed in South Africa’s democratic development.

The struggle (to be heard)

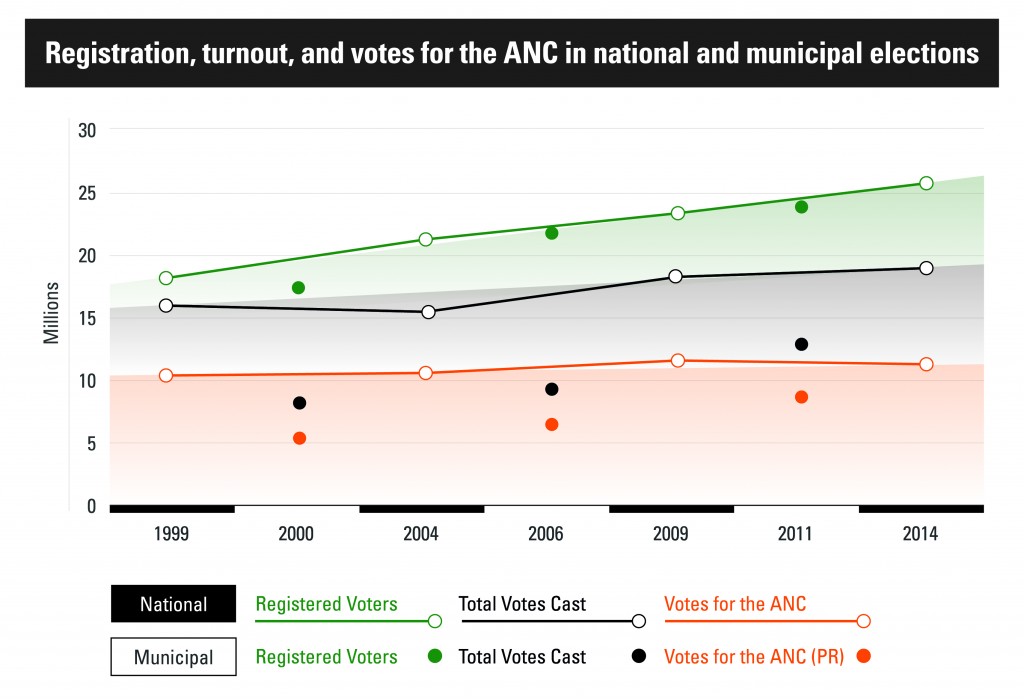

On 3 August, 26.3 million citizens will be eligible to vote – 42.5% more than registered for municipal elections in 2000. However, participation in electoral politics has declined: 18.7 million South Africans cast ballots in the 2014 national and provincial polls, equivalent to 57% of the voting age population, down from 72% in 1999.[2]

A remarkable 48.6% of the electorate have come of age since the end of apartheid in 1994, but young people remain disproportionately under-represented. While 93% of South Africans over 40 are registered to vote in local elections, this figure falls to 79% among those aged 30–39, and to 55% for those aged 20–29.

The diminishing appeal of electoral politics can in part be explained by the dominance of the ANC, seemingly invincible with more than 60% of the vote in 2014. Flagging support for the party’s leader, Jacob Zuma, is another factor. The president has been embroiled in a succession of corruption scandals, and the compatibility of his style of leadership with the tenets of a constitutional democracy is widely – and volubly – questioned. Justice Malala, a prominent political commentator, recently cast Zuma as “a sexist, homophobic, crass, incapable and shameless man who has handed over important and prominent cabinet posts to his friends… With him have come patronage and mediocrity.”[3]

Lack of accountability has also caused disillusionment and apathy. South Africans do not directly elect the head of state, who is appointed by parliamentary ballot. The legislature is elected by proportional representation (PR), with the result that members of parliament (MPs) serve at the behest of powerful parties, owing their position to a ranking on a PR list. In the case of municipal government, voters cast ballots for both a ward councillor and a party; yet parties can recall councillors in both categories. In a 2015 survey, two-thirds of voters stated that they had no access to ward councillors or knew how to reach them.[4] Radical activism is eclipsing electoral politics.

In 2014, 218 “service delivery protests” were recorded in South African municipalities, ranging from the blockading of roads to destruction of government buildings.[5] Received wisdom has it that such protests tend to peak in non-election years, and dissipate when MPs and councillors attempt to resolve community grievances in return for support at the ballot box. However, violent protest linked to political battles within the ANC have marked June and July 2016. Electoral competition is becoming ever fiercer.

Comrades for the council

With over one-quarter of South Africans unemployed, and many more having given up looking for work, election to municipal office is a prized opportunity. Such roles “can mean the difference between being middle class and being unemployed”, asserts Steven Friedman, director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy at the University of Johannesburg.[6] They are also lucrative. A part-time representative in the smallest municipality (grade 1) can be paid as much as R207,455 a year. A full-time committee chair in a grade 1 municipality could earn R482,357, while in a grade 6 council, this could rise to R877,968. The mayors of the eight metros are entitled to up to R1,242,409 – more than the starting salary of an MP.[7]

Councillors are entrusted with access to resources, power and influence. They are responsible for determining how contracts are awarded. “Tenderpreneurs” use political connections to obtain contracts, often in return for a kickback to the party or individuals. Paul Graham, southern Africa director at Freedom House, a democracy and rights watchdog, told ARI that “using public office for personal gain has become normalised under the Zuma administration”. The practice of “cadre deployment” – providing the politically connected with salaried positions in government – is commonplace.

ANC Secretary-General Gwede Mantashe has admitted that the battle for patronage and competition between “tender beneficiaries” contributed to pre-election violence in Tshwane, a Gauteng province metro which encompasses the administrative capital Pretoria.[8] A factional conflict between supporters of incumbent mayor Kgosientso “Sputla” Ramokgopa and ANC Deputy Chair for Tshwane Mapiti Matsena could not be resolved and risked derailing the party’s campaign in the metro. The ANC’s decision to parachute in Thoko Didiza – a figure disconnected from local politics – exposed the priority afforded to internal dispute resolution.[9]

Tshwane also highlighted the shortcomings of ANC “slates”. This form of block voting has been standard practice since the party’s Polokwane conference in December 2007, which hastened the recall of Thabo Mbeki as president of South Africa. The zero-sum nature of factional battles has precipitated an increase in the use of violence. In KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and Mpumalanga provinces individuals overlooked in candidate selection have orchestrated political assassinations, with the intention of forcing a by-election or moving up a PR list.

An estimated 450 political assassinations occurred in KZN between 1994 and 2014.[10] During the past two years, 64 people have been killed at Glebelands Hostel in Durban, in what “started as a fight over the allocation of beds but has escalated into an intra-ANC strife”.[11] Twelve ruling party cadres were executed in KZN in June-July 2016.[12] The alarming statistics for Zuma’s home province raise questions about the ANC’s ability – and desire – to maintain law and order there.

In Mpumalanga, violence has also become a feature of politics. An ANC deputy chairman, Michael “Zane” Phelembe, was shot dead outside his home in May. He had opposed plans regarding the award of lucrative local infrastructure deals. As violent contestation has escalated, ideological divides within the ruling party have seemingly disappeared. Raymond Suttner, a former anti-apartheid activist who now lectures at Rhodes University, contends that there has been “a broader depoliticisation of the ANC as the drive for spoils displaces political ideas.”[13]

Shifting constituencies

Policy debates may be a thing of the past, but the ANC knows how to put on a show for voters. The party enlists prominent musicians to play at “car washes” where election candidates dispense T-shirts, posters and alcohol before touring local shebeens and hairdressers. In economically marginalised areas, the opportunity to receive handouts is attractive. While nationally only one in four South Africans say they attended an election campaign rally in 2014, in Mpumalanga the figure was 48%. The ANC received 78.8% of the provincial vote.

This type of electioneering comes at a cost. South Africans have come to expect an increase in corruption ahead of elections as state coffers are looted by those charged with fundraising. During a May 2016 visit to London, Dr Zweli Mkhize, ANC national treasurer and KZN “kingmaker”, joked that he was looking for donations as “the cost per vote keeps going up!”. In a 2015 Afrobarometer survey, the majority of respondents agreed with the statement that “voters are bribed”, with 27% feeling this occurred invariably and 28% occasionally.[14]

Besides its access to resources, the ANC has a trump card: identity politics. In April 2016, Zuma told a rally in Melmouth, KZN, “We have a problem as black people. Some people don’t even go out there and vote. Every elderly white person goes out there to vote because they know how important voting is.”[15] Ebrahim Fakir, manager of governance institutions and processes at the Electoral Institute for the Sustainable of Democracy in Africa, told ARI that “playing the race card may provide the ANC with a quick win, but this tactic is not sustainable in the long term.”

In the meantime, ANC figures at all levels routinely refer to its major opponent, the Democratic Alliance (DA), as a “white party”. The threat posed by the DA has increased since it began targeting the black middle class. The party’s share of the vote in urban areas increased from 17.9% in 2004 to 30.2% in 2014, largely thanks to support from young professionals. StatsSA estimates that the proportion of South Africans living in towns and cities is 62% and rising. While rural turnout decreased from 77.6% in 2004 to 69.9% in 2014, in urban areas it marginally increased.[16]

Urban workers played an instrumental role in bringing the ANC to power, through the United Democratic Front. This incorporated the labour movement, churches, civil society and student activists, and adopted the ANC’s Freedom Charter, co-operating with the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the underground South African Communist Party (SACP). However, the ANC’s share of the urban vote has declined significantly, from 66.8% in 2004 to 55.8% in 2014. In a 2015 opinion poll, only 42% of city dwellers said they would vote for the ruling party.[17]

Conscious of its declining national support, the ANC moved to capture a political constituency held by the Inkatha Freedom Party in KZN.[18] In 1999, only 11% of the ANC’s national vote came from the province, compared to 24% from Gauteng. In 2014, KZN and Gauteng both accounted for 22% of the party’s national vote. The ANC also controls every municipality in the predominantly rural provinces of Free State, Limpopo and Mpumalanga. Prof. Ivor Chipkin, executive director of the Public Affairs Research Institute has observed that, “The ANC is becoming a regional, ethnic party.”[19]

To that charge, can be added one of systemic corruption. Irregular expenditure by South Africa’s municipalities more than doubled between 2010-11 and 2014-15, when it reached R14.75 billion. During the same period, fruitless and wasteful expenditure increased from R273 million to R1.34 billion.[20] The auditor general only has the power to report on the worsening situation, not to remedy it. That responsibility falls to elected officials, but even where the political will exists, municipalities often suffer a skills shortage. In 2014, the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs reported that 170 of 278 municipal chief financial officers did not hold qualifications appropriate for their role.[21]

Technocrats in the town hall

Exploiting these failings, the DA has promised “honest government”. Its campaign has stressed the party’s record in Western Cape, where it runs the province and the City of Cape Town, and governs two-thirds of the municipalities. In 2014-15, 73% of Western Cape municipalities were awarded clean audits. The DA cultivates a reputation for “doing things by the book”. The party runs, either alone or in coalition, nine of the 10 top-ranked municipalities in the Government Performance Index.[22]

Through “Blue the Network”, the DA has appealed to “young professionals wanting to bring about meaningful change in South Africa”. This has enabled it to recruit new members and a pool of prospective candidates with experience of business and finance. Applicants are interviewed and tested prior to selection, then provided with relevant training. This focus on skills contrasts with the fierce – and sometimes physically violent – competition that characterises ANC primaries.

However, the DA remains hamstrung by its perceived lack of diversity. Although technically the most representative of South Africa’s political parties, the shortage of older black males in the party leadership is notable. The party’s Young Leaders Programme promotes diversity across the DA, and has introduced under-35s from all racial backgrounds into party structures, local and provincial government, and parliament – but it will take time to change entrenched perceptions.

The DA has put up candidates for the 2016 municipal elections in every single ward in the country, a feat unmatched by the ANC. However, 45% of its representatives are standing for multiple positions, despite election to one office alone being permissible by law. The DA is also accused of an urban bias. Nkanyiso Gumede of the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) has observed that the party’s manifesto contains “absolutely nothing on agriculture, rural development, land reform or farm workers, raising the question of whether or not the DA recognises that there is a large rural constituency.”[23]

Mmusi Maimane, the DA’s 36-year-old leader, is a gifted orator and “media savvy”. His decision to refer government maladministration to the public protector (an ombudsman) and the courts has proved effective. But sustained attempts to call a vote of no confidence in Zuma, despite the ANC’s huge parliamentary majority, attest to an interest in seeking headlines. Appeals to the government to raise social grants – a range of welfare payments that the ANC initiated – at a time when the national budget is under intense pressure, displays a degree of political opportunism. The enthusiasm for the social grant system and the party’s endorsement of the National Development Plan has prompted debate about whether the DA is merely “ANC Lite”. Winning a metro in Gauteng, or Nelson Mandela Bay in Eastern Cape, would put this suggestion to the test.

Left out

The ANC, COSATU and the SACP maintain a “Tripartite Alliance”, but this is fracturing amid controversy over Zuma’s clientelism. The Communist Party has talked up “state capture” and promised a “mass action” campaign against members of the Gupta family, who have allegedly profited from personal ties to Zuma, but has stopped short of directly criticising the head of state. Ranjeni Munusamy, associate editor at the Daily Maverick, told ARI that the Young Communist League wants the SACP to field its own candidates in future elections.

In public, COSATU endorses the ANC but its credibility is diminished. “COSATU has lost muscle”, Munusamy told ARI, stressing its declining membership amid a shift away from the shop floor and towards public sector jobs. The mining sector used to constitute the labour federation’s largest affiliate until more urgent, radical voices eclipsed ANC-linked unions. Wildcat strikes in August 2012, and the massacre of striking workers at the Lonmin mine in Marikana, saw the rise of the independent Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union at the expense of the National Union of Mineworkers.

In November 2014, in another significant development, COSATU expelled the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA). When Zwelinzima Vavi, then COSATU’s general secretary, spoke out against the expulsion, he too was dismissed. Vavi and NUMSA’s general secretary, Irvin Jim, plan to form a new labour federation, unionising hitherto marginalised workers and appealing to those in the informal sector.

That Vavi and Jim have not yet made their move is testament to the growing presence of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) since the party’s formation in July 2013. Although the EFF achieved only 6.4% of the national vote in April 2014, it won representation in all nine provinces and became the official opposition in two provincial legislatures, Limpopo and North West. The party is untested at local level, but its widely anticipated success could be the headline of the 2016 municipal elections.

Revolutionary councillors

The rise of the EFF can be attributed to the personality of its leader and the appeal of his populist narrative and dress code. Julius Malema, the party’s “commander-in-chief”, is a former ANC Youth League leader who once pledged to die for Zuma. Malema has since become a thorn in Zuma’s side, describing him as “an illegitimate president”, “morally and politically compromised”, and calling for his “immediate removal” in response to the 2016 state of the nation address. [24]

Malema has branded the EFF as a party of the working class, the neglected and the marginalised. It has gained a foothold in constituencies disaffected with the ANC, including the “unhitched” labourers whose precarious existence has not changed since the apartheid era. The party’s powerful, racially charged discourse on land appeals to those living in townships and backyard shacks. Its uniform – red overalls and hardhats, interchanged with military fatigues and red berets, or pinafores – is distinctive, and its conduct calculated to attract attention. Numerous EFF MPs have been forcibly removed from the parliamentary chamber for rambunctious behaviour. The EFF has also tapped into the spirit of rebellion among black students at South Africa’s universities. Party activists buttressed the #RhodesMustFall movement, and subsequently #FeesMustFall, wrong-footing the ANC Youth League.

Casual labourers are unlikely foot soldiers for an election campaign, but the party has actively sought to represent their interests nevertheless. The EFF manifesto demands that all companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange pay a minimum wage of R4,500. Those employed in specific manual roles would be entitled to additional salaries. Mineworkers would receive R12,500 per month; private security guards, R7,500; builders, R7,000; factory workers, R6,500; and petrol attendants, cashiers and farm labourers, R5,000.[25] The manifesto also promises to “expropriate and allocate land equitably to all residents of the municipality”. Africa Check found this proposal to be unworkable in the absence of ministerial approval and funds for compensation.[26] Similarly impractical is a pledge that half of all goods sold in the municipality would be produced locally.

The EFF finds itself at a critical juncture. It must now decide whether it is to be an entertaining protest movement or a party willing and able to govern. If it has sufficient councillors to hold the balance of power in a municipality, it will be presented with an opportunity to access paid positions and influence resource distribution. Should it refuse to join a coalition, it could lose support and be portrayed as politically irrelevant. If it accepts, the EFF will be expected to dispense more than populist bombast.

Malema has done all he can to distance himself from the party that spawned him. In June, he told a crowd in Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga, “You are in an abusive relationship with the ANC. It beats you up and you go back and say you love it.”[27] Despite his claims that the EFF “will never work with the ANC”, some suspect Malema of planning a return to the fold once he has shown his ability to garner more than 10% of the vote.

Crossing the Rubicon

South Africa’s political landscape is increasingly pluralistic. Each election now brings a more concerted challenge to the unrivalled supremacy that the ANC has enjoyed since 1994. The 2016 municipal elections will confirm as much. Fewer than one in three South Africans of voting age are likely to turn out to support the ANC on 3 August. Traditional supporters may engage in tactical voting – splitting their votes across ballots for ward and PR councillors – in the hope of electing a candidate with the inclination to fix dilapidated local infrastructure and the nous to improve municipal finances.

Should the ANC lose control of one – or more – of its seven metros, there will be immediate and intense speculation about the party’s ability to dominate the April 2019 national and provincial elections. There is already conjecture that, faced with the prospect of losing Gauteng province in 2019, the ANC may “self-correct”, recalling the president at the next national conference in December 2017. But Zuma’s grip on power is entrenched. All the provincial premiers remain loyal to him, and many others depend on his patronage. Against the backdrop of rapidly changing demography, some regard his close ties with rural constituencies as an electoral bulwark rather than an existential threat to the ANC.

Political pluralism, at least in South Africa’s cities, is synonymous with increasing divergence. The character and approach of the parties being watched most closely – the ANC, DA and EFF – could not be more different. Where coalitions become necessary after 3 August, they will have to be negotiated and fashioned by those advancing disparate and incompatible policy prescriptions to local and national issues. This process will produce important insights into the near-term development of democracy in South Africa.

At the 2011 municipal elections, when 57.6% of registered voters turned out, the DA was the major beneficiary of a heightened interest in local politics.[28] In 2016, the EFF may profit from widespread frustration at the state of government. It remains to be seen whether technocrats and revolutionaries can collaborate in government, but the opportunity to revitalise South Africa’s maligned municipalities is theirs for the taking.

Interviews were conducted in April 2016. Africa Research Institute and Nick Branson would like to express their gratitude to those who contributed.