As South Africa marks the centenary of the 1913 Natives’ Land Act, which effectively excluded the black population from ownership of some 90% of land, Africa Research Institute (ARI) examines the record and prospects of the land reform programme. In its latest Briefing Note Waiting for the green revolution, ARI argues that without greater financial and political commitment from the government, land reform will continue at its slow pace. A bolder approach to restructuring South Africa’s rural economy is needed.

As South Africa marks the centenary of the 1913 Natives’ Land Act, which effectively excluded the black population from ownership of some 90% of land, Africa Research Institute (ARI) examines the record and prospects of the land reform programme. In its latest Briefing Note Waiting for the green revolution, ARI argues that without greater financial and political commitment from the government, land reform will continue at its slow pace. A bolder approach to restructuring South Africa’s rural economy is needed.

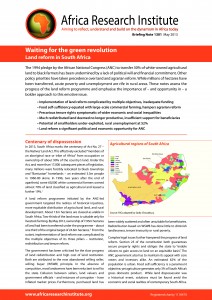

In 1994, the African National Congress (ANC) pledged to redistribute 30% of white-owned agricultural land to black farmers by 1999, and to restitute property lost as a result of racist legislation. By 2012, 7.95m hectares had been transferred, about a third of the 24.6m hectares originally targeted. An estimated US$3.2 billion was spent on the land reform programme between 1994 and 2013 – equivalent to a single year’s budget for housing development.

Successive administrations in Pretoria have equated national food security with large-scale commercial farming – a sector dominated by white South Africans. The potential of millions of black smallholders to increase production and create much needed jobs has been overlooked. The government has prioritised grafting redistributed land onto existing commercial units. But large farms can no longer be relied on as generators of increasing rural employment. Between 2006 and 2012, the number of South Africans employed in agriculture fell from 1.09 m to 661,000.

“While land dispossession was a historical event, solutions must be found amid the economic and social realities of contemporary South Africa,” says ARI’s Dr Piotr Cieplak. “Although the speed of redistribution matters, simple shunting of hectares is not sufficient. Land reform must go hand-in-hand with a restructuring of the rural economy. This may take a generation – or more,” he adds.

Much redistributed land has been deemed “no longer productive” by the South African government. Acute poverty is rife in rural areas. Unemployment stands at 52%, twice the national average. Concerns of rural voters in a country with an urbanisation level of 63% appear to be of secondary importance.

Against the backdrop of subdued economic growth, widespread industrial unrest and rising inequality, meandering land and agrarian reform will become increasingly susceptible to political opportunism. During his leadership of the ANC Youth League, Julius Malema made Zimbabwe-like expropriation of white-owned land one of its main rallying calls. “The land question must be resolved, if needs be the hard way,” Malema said, quoting Oliver Tambo – an emblematic figure in ANC’s history.

“The ANC should see land reform as an opportunity to revive the rural economy,” says ARI’s Director Edward Paice. “Recent policy developments may speed up land transfers, but critics predict more red tape, lengthy legal challenges from landowners – and the alienation of commercial farmers. Far greater financial and political commitment to land and agrarian reform is required to move things on.”

Notes to editors:

Africa Research Institute is an independent, non-partisan think-tank based in London. Our mission is to draw attention to ideas and initiatives that have worked in Africa, and identify new ideas where needed. Waiting for the green revolution: land reform in South Africa can be downloaded from the Africa Research Institute website: http://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/publications/briefing-notes/waiting-for-the-green-revolution-land-reform-in-south-africa/

For media enquiries, please contact Edward Paice or Piotr Cieplak on 0207 222 4006 or 07791055372