On Wednesday 8 October 2014, ARI, in partnership with the Sheffield Institute for International Development (SIID), hosted a discussion focusing on contemporary cases of urban violence in Africa. Dr Tom Goodfellow explored violent protest in Uganda, Dr Paula Meth reflected on gender-based violence in South Africa and Zainab Usman discussed Boko Haram violence in Nigeria.

Key Information

- In 2013 ARI launched publications and hosted events scrutinising the state of urban planning law and the education of urban planners in Africa.

- This was followed in February 2014 by a book launch of “Africa’s Urban Revolution”, edited by Edgar Pieterse and Susan Parnell of the African Centre for Cities. A review of the book can be found here

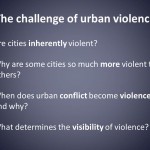

- Civic conflict refers to diverse but recurrent forms of violence between individuals and groups and can include organised violent crime, gang warfare, terrorism, religious and sectarian rebellions, and spontaneous riots or violent protest over state failure such as a poor or absent service delivery. Civic conflict can sometimes overlap with civil conflict; however it differs from it in that civic conflict is ultimately a demonstrative or reactive process, demanding participation and response but rarely seeking to take control of formal structures of power.

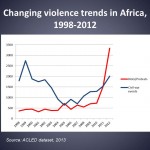

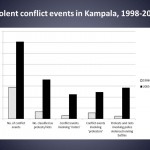

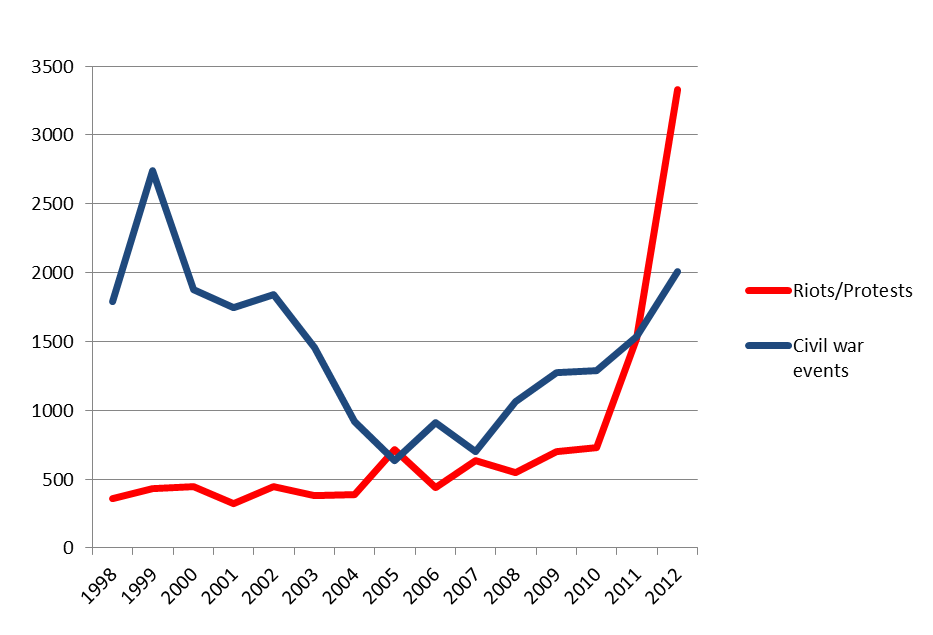

- Graph depicting the growing prevalence of riots and protests over more conventional forms of violent conflict (Source: ACLED 2013 dataset)

Protest as Voice

Dr Tom Goodfellow

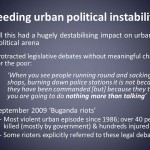

The stark statistic that three times more people die each year from interpersonal violence rather than from war is where Dr Tom Goodfellow began his discussion on civic conflict. Cities are not intrinsically violent. In seeking to understand what drives violence, with a specific focus on Uganda, Tom made three key observations:

- Violence can be caused by increasing proximity to others but that people still flee to urban centres to escape conflict and cities can in fact be centres of solutions to conflict.

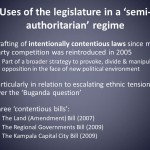

- Protests or riots can become a norm of civic conflict when formal ways of participation are blocked or controlled by a central state authority, referencing the Buganda Riots (2009) and Walk to Work Protests (2011) in Uganda.

- In Uganda, President Museveni has been able to manipulate the political environment so that protestors are given space to perform and express a voice without necessarily being heard or posing a threat.

Housing Violence

Dr Paula Meth

Violence in the home and public realm are increasingly intersecting and overlapping. Paula emphasised the need to understand the location of this conflict and to recognise that men and women are both vulnerable. Reflecting on her research in South Africa she made three key observations to the audience:

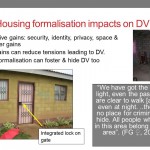

- Domestic violence is more likely in informal housing settlements where there is a lack of privacy and space, as this exacerbates tensions.

- There is a general failure to recognise fully the male experience of violence, as both perpetrators and victims (often they can be both), particularly in cities.

- The formalisation of housing can reduce levels of violence. In South Africa, the government funded re-housing programme has provided improved quality of living, which in turn enhances a citizen’s sense of worth. However, it can also create new form of violence as people compete for new homes in what is a highly politicised process. Moreover, formal structures, with their enhanced privacy, can inadvertently conceal domestic violence.

Politicising Insurgency

Zainab Usman

Zainab Usman remarked on the deterioration of trust amongst communities in Northern Nigeria that had lived in peace before the resurgence of Boko Haram in 2011. Reflecting on the composition of the Federal State of Nigeria and the escalating violence in 2014 that has caused thousands of deaths, Zainab made three critical observations:

- Whilst the central government has the capacity to address the insurgency, it lacks the political will to do so.

- In the context of the upcoming presidential elections, scheduled for February 2015, it is in the political interest of the ruling party to do little about instability in what is generally regarded as an opposition stronghold; but the opposition is also wont to exploit the situation for political ends.

- The diverging political narratives around the insurgency are merely illustrations of the governance challenges bedevilling every aspect of Nigerian society.

Questions/Answers

Q. The panel was asked to reflect on the masculinities of violence at national, street and household level:

PM: Gender violence is not just economic or political but needs to be understood through a cultural norms lens too.

TG: Protests are quite masculine in the way and space in which they occur. Urban protests are often very male-dominated in terms of who participates.

Q. What about the theme of migration in urban violence as it links closely to identity and belonging or ethnicity; does this have a substantive impact on civic conflict?

PM: There is a rural-urban dimension as men in particular can feel a loss of manhood by moving from rural areas, where they have power or authority, to urban locations, where this authority can be eroded. Half of refugees live in urban areas so they obviously experience urban violence, but how they influence the process is not yet clear.

ZB: The border with Cameroon has been a major exchange point for Boko Haram activity but the extent to which this has fuelled the insurgency is not clear.

TG: In Kampala, migrants have not yet played a central role in violence; but in Northern Uganda there was a migration dynamic, related to the conflict, where young men challenged the role of traditional of elders; creating a crisis of masculinity. Adam Branch has written about this.

Q. What is the effect of gated communities/ integrated cities on urban violence and what is the relationship between the two regarding access to services/poverty?

PM: Gated communities are an emerging phenomenon on the continent and create settings where domestic violence can be very well-hidden. Some research suggests that they can be sites of increased domestic violence – but still the poor want to live in these areas. This is mainly because they reduce the risk of another type of urban violence – crime.

TG reflected on the issue of governable space and making space ungovernable, both of which are intimately linked to violence. He noted that this can include space beyond the control of the state and space that state exclusively controls.

Q. Does Boko Haram activity fuel and trigger further violence at the community level or do communities foster resilience?

Referring specifically to the bombings in Jos, ZU said she believed that the event had actually fostered a greater sense of community unity and resilience rather than creating divisions. However she acknowledged that in other areas this might not be the case and that violence, at the community level, may be caused the insurgency.

Audio podcast:

[audiomack src=”https://www.audiomack.com/song/africaresearch/urban-violence-in-africa-understanding-civic-conflict-1″]

Video of speaker presentations and the Q&A session:

To select the recording for a particular presentation, click the Playlist menu on the top left

Tom Goodfellow’s slides:

Download a PDF of Tom Goodfellow’s slides

Paula Meth’s slides:

Download a PDF of Paula Meth’s slides

Recommended reading:

Legal Manoeuvres and Violence: Law Making, Protest and Semi-Authoritarianism in Uganda (Wiley Online Library content, access restricted, login required)

Toying with the law? Reckless manipulation of the legislature in Museveni’s Uganda

From ‘civil’ to ‘civic’ conflict? Violence & the city in fragile states

Boko Haram and the competing narratives

Related ARI content:

Conflict in Cities: In conversation with Jo Beall