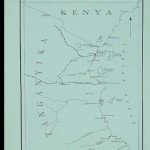

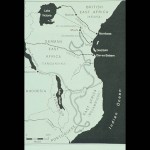

Edward Paice, ARI Director and author of “How the Great War Razed East Africa” and “Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa”, spoke at length about the East African experience of the Great War on the eve of Remembrance Day at the Houses of Parliament.

The lecture, co-hosted with the Africa APPG, was followed by a Q&A session that provided an opportunity for audience members to engage in the discussion. Here is a sample:

Q: Conflict in the Great Lakes region continues to this day. Are strands of this conflict traceable back to the Great War? And have lessons been learned?

A: Broadly speaking, if lessons of war had been learnt we would not continue to see so much fighting across the globe. What continues to be sobering is that in modern conflict, it is usually civilians who suffer the most, often at the hands of military personnel. The situation in northern Nigeria is just one example of this.

Q: Are there sources available that provide evidence of why Africans fought in the Great War from their own perspective?

A: New material is constantly being uncovered although the sample is not huge. In August 2014, the BBC broadcast recordings of Africans who served as carriers, reflecting on their experiences of the conflict.

People initially joined the fight entirely voluntarily and for similar reasons as they did in Europe; the uniform, a sense of adventure, the pay and potential prestige. As the conflict progressed and the hardships became more apparent this changed. In the case of service as carriers, men were increasingly press-ganged. So too were some soldiers later on. Carriers faced the most terrible conditions and I would be very surprised if anyone volunteered for this role from mid-1916 onwards.

Q: Are there African historians and universities recognising and researching this period?

A: Yes. During my own research I worked closely with staff from the National Archives in Nairobi and Harare to name just a couple.

Generally, memorialisation of the Great War is not as prominent in Africa as it is elsewhere. That said, with 2014 marking the centenary of the beginning of the war, far greater global attention has been given to the African narrative than ever before. Some initiatives have been launched by African governments to recognise the loss of life and destruction that the conflict brought upon their people. This is to be welcomed. All societies need to reflect on the past in order to evolve.

My hope is that by 2018, there will be much greater and wider recognition of the impact this cataclysmic four years had on the continent.

Q: The treatment of the King’s African Rifles and other African regiments fighting for the Allied forces in Burma during the Second World War was significantly better. To what extent was this improvement a result of the terrible conditions of service experienced during the Great War?

A: Lessons were taken on board. However, I believe that a lot of the mistreatment was not deliberate. Poor overall coordination and logistical challenges characterised the conflict and were never properly addressed. Control was lost completely during the 1916 advance and never regained.

There were of course individual cases of cruelty and neglect, but on the whole there was little deliberate intent behind the appalling conditions that soldiers and carriers were forced to endure. It was a combination of unique circumstances. Comparable conditions were never experienced in conflicts in Africa that preceded or followed the Great War.

Q: What do you think of Charles Miller’s interpretation of the conflict, in particular the role of von Lettow-Vorbeck, in his book “Battle for the Bundu”?

A: It’s a very readable book, but as a historian I have difficulty with a narrative that portrays German commander von Lettow-Vorbeck as a heroic figure. This fails to take into account the consequences of his conduct of the war on local societies. They suffered most of all. But von Lettow-Vorbeck and his fellow officers, with only one or two exceptions, displayed no guilt whatsoever in the aftermath of the war, stating that 2 million people had “willingly served the German war effort”. Many Allied officers were much more reflective and had a genuine realisation that something terrible had occurred as a result of the fighting. I would add that von Lettow-Vorbeck was certainly a competent and determined commander but I don’t think he was better than many on the Allied side – like General Northey, for example.

Q: How much did the conflict accelerate or delay the process of decolonisation?

A: The British government may not have wanted stories of war casualties aired widely, particularly the death toll among civilians and carriers, but they were well aware that the so-called European “civilising mission” in Africa was in tatters. After the war, imperialism donned new clothes. Lip-service was paid to the need for development. The problem, in the aftermath of war, was that there was no money to act on the rhetoric.

Nationalist leaders did not emerge until after the Second World War and there is little evidence to suggest that the roots of nationalism lay in the Great War. In short, it neither hastened nor sped up decolonisation.

Q: Did the British adopt a strategy to recruit specific tribes with a long-term view to ensuring their control of particular territories?

A: No colonial power thought it was going anywhere, for a long time. In fact they were thinking more about enlarging territories and extending control. As a consequence there was no thought given, or scheme put in place, to ensure that special “friends” were made.

Decisions regarding who to recruit were generally based on the perceived warlike qualities of tribes. Many of those which had been most hostile to the imposition of colonial rule, like the Nandi of Kenya, provided large numbers of soldiers.

Audio podcast:

Slides:

Photos:

Related ARI content:

Publication: How the Great War Razed East Africa

Blog: The Great War and the butcher’s bill in Africa