This is the first of two guest posts by Dr Chloé Buire examining the expansion of suburban Luanda. It focuses on Panguila, a relocation settlement for residents of Luanda’s slums, and chronicles the experiences of the Domingos family (all names have been changed). The second article considers Kilamba New City, a satellite town designed for the country’s emerging middle-class.

Although radically different in scale and vision, Panguila and Kilamba are both state-planned but foreign-constructed settlements on Luanda’s periphery. They exemplify the rapid suburbanisation of Angola’s capital and provide insights into the regime’s vision of modernity.

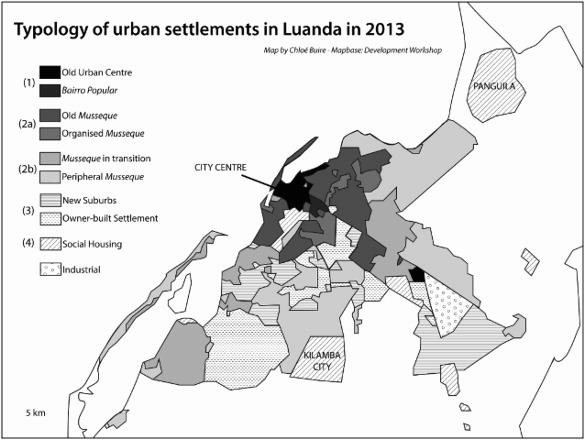

Luanda, like many post-colonial cities, retains a pronounced divide between the city centre, planned for European settlers, and the unplanned periphery, characterised by self-built structures housing the African population. Locals use the term cidade to refer to the city centre, while labelling the districts which now surround them as musseques, literally “places of red earth”.

Following the Portuguese exodus upon the declaration of independence in 1975, properties in the centre were awarded to supporters of the national liberation movement, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA). During the civil war which followed, Luanda became a site of refuge for those affected by the conflict, leading to a rapid expansion of the musseques. The city’s population grew from 500,000 in 1975 to approximately 3.5 million by the time of the MPLA victory in 2002. The city is now home to an estimated 6.5 million inhabitants.

Contemporary Luanda exhibits a remarkable tension between unplanned sprawl, resulting from self-construction from below, and attempts to regulate from above, through eviction and demolition. In the absence of urban planning, population densities in the musseques exceed 100,000 people per square kilometre, while there is a shortage of land on which to build new roads, bridges and drainage canals. In their quest to construct a modern city, the MPLA resolved to demolish informal settlements which occupied precarious positions on hillsides or on riverbanks prone to flooding and landslides, and resettle their residents in new Social Housing Zones (SHZ).

Panguila, approximately 30km north of Luanda, was opened by President José Eduardo dos Santos (JES) in January 2003. Although the first 1,000 homes were built by a Chinese corporation, Golden Nest International, companies from Brazil and Israel constructed subsequent ‘sectors’. Angolan civil servants were responsible for distributing the new houses, with all the rent-seeking opportunities that might entail.

Helena Domingos was one of the first to move into an apartment in Panguila, after her family’s property was demolished to make way for a motorway. At that time, the only road linking Luanda and its satellite town was in such a state of disrepair that it took Helena over two hours to reach the cidade. Initially, she spoke of having been banished to the bush, far from the civilised world, limiting her access to government services. Helena’s neighbours, she said, were sinking into depression. One suffered a cardiac arrest as a result of the stress.

Rather than fall into this trap, Helena enlisted family members to help her make the new house feel like a home. She fenced the plot, installed a water tank and an electricity generator, and gradually built an extension. Incrementally upgrading housing through small investments was the norm in the musseques; but it was a novel approach in the suburb of Panguila with its orderly street patterns and defined plots.

Thus, in Panguila, formal and informal development ran in parallel. The government financed the construction of nine sectors in total, each of which have a different style and community. Scandals would occasionally erupt when families expelled from the city centre arrived in Panguila to find the houses promised to them were already occupied. The majority of properties were, however, sold on a quasi-regulated market, with civil servants turning a profit.

For the Domingos family, relocation to Panguila provided an unexpected windfall. Among the first wave of occupants, Helena’s kin were well-placed to benefit from what has been initially viewed as a misfortune. João, Helena’s step-brother, successfully exploited his connections to the ruling party to purchase an end-of-row property, enabling him to extend the plot.

Social housing in Panguila may not be as desirable as Luanda’s gated communities, Benfica and Tatalona, but it has provided the Domingos family with the opportunity to build a new life in the city’s suburbs. This new periphery has broken the dichotomy between the cidade and the musseques by presenting an alternative form of modernity where well-connected Angolans can transform their living conditions through patient investment.

Dr Buire is a post-doctoral research associate at Durham University, UK. She was previously a post-doctoral fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. In January 2016, she will take up a new post at the CNRS / Laboratoire Les Afriques dans le Monde, in Bordeaux, France. Her work on Luanda was originally published in African Studies under the title, ‘The Dream and the Ordinary: An Ethnographic Investigation of Suburbanisation in Luanda’.