This is the second piece in a series on Tanzania’s proposed constitution – or katiba – written by Nick Branson. In this instalment we outline how continuity has prevailed over change in relations between the executive and the legislature, and how the political parties could exploit new provisions for gender parity.

The United Republic of Tanzania has successfully endured by balancing tensions between its two constituent parts – mainland Tanganyika and the Zanzibar Isles – at the apex of government. Under the 1964 Acts of Union, the President of Zanzibar was to serve as deputy to the Union president ex-officio, but changes in 1977 established an independent vice-presidency. From then on, the vice-president was to be elected on a joint ticket with the head of state, with the caveat that the candidates come from different parts of the Union.

Article 99 of the proposed constitution adds to this already complex arrangement by providing for a third vice-presidency, to be held by the Union prime minister. In an apparent contradiction, Article 100 maintains the requirement that the president and his deputy be elected on a joint ticket, but Article 85(ii)(b) states that the first vice-president must be “confirmed by a majority of votes in parliament” within fourteen days. What would occur if the National Assembly were to reject the candidacy of the deputy president?

Reinstating a provision removed in 2000, Article 89 requires the president to receive at least 50% of the popular vote, and provides for a run-off election between the top two candidates in the event that neither passes this threshold. With the incumbent president, Jakaya Kikwete, stepping down in 2015, and the opposition alliance, Ukawa, threatening to unite behind a single candidate, Tanzania could see its first serious competition for the highest office. In the event that the result is disputed, Article 90 enables presidential candidates to file a petition at the Supreme Court for the first time.

A crowded cabinet

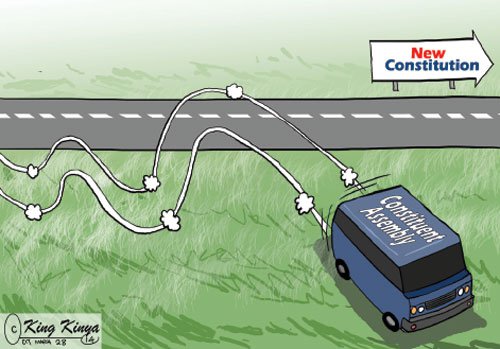

Whoever is elected president, they will retain the power to reward a considerable number of their supporters with roles in government. Despite the recommendation of the Warioba Commission that the cabinet be limited to 15 ministers, Article 115 would see the figure capped at 40. In an effort to separate the branches of government, Warioba recommended that members of the National Assembly, or Bunge, and the Zanzibar House of Representatives be ineligible to serve as ministers. Yet the Constituent Assembly rejected this proposal and instead made holding parliamentary office a requirement for serving in the cabinet, incentivising aspiring ministers to show their loyalty in the chamber.

Even if the executive and legislative are a little cosy, Bunge would become more diverse under the proposed constitution. Article 129(iv) provides for equal representation of men and women, improving on a 30% gender quota at present. Parliament must legislate on the detail, but the existing system of special seats will likely form the basis of bringing this about. Accordingly, the total number of MPs could fluctuate between 340 and 390.

Power to the parties

However, the legislation enshrining gender parity risks undermining the independence of Bunge as an institution. If the number of appointees to the chamber is increased, the party whips will gain even greater leverage over their parliamentary caucuses. Threats to replace noncompliant MPs with others who would toe the party line would stifle dissenting voices. Crossing the floor to join another party remains outlawed, as MPs must stand down if they leave the party which elected them under Article 143(g) of the proposed constitution.

By contrast, Warioba sought greater protection of Bunge, proposing that one male and one female representative should be elected by every constituency, rather than empowering the parties to top-up their caucuses with appointees. This was vetoed by the Constituent Assembly along with the recommendation that MPs should only serve a maximum of three five-year terms. That might have improved the injection of fresh ideas into parliament; instead, the same party stalwarts will continue to sit in Dodoma for as long as they wish.

A further innovation that could transform the dynamics in Dodoma is the addition of independent candidates, permitted for the first time under Articles 140(i)(c) and 216(i). This was a major bone of contention for the authors of ARI’s publication, Bunge Lenye Meno: A parliament with teeth for Tanzania, one which we intend to revisit once the new legislature is established in November 2015.

The final instalment in this series considers how the proposed constitution has retained historical language and values, but attempted to balance these with new rights and responsibilities.

Find Part I, which explores the structure of the Union between mainland Tanganyika and the Zanzibar Isles, here.