Government in Nigeria “is detached from its people at every level of the federation”, said Chidi Odinkalu, chair of the National Human Rights Commission, when interviewed for ARI’s 2016 briefing note “State(s) of crisis”. For most Nigerians, the state and unelected local government authorities are the most proximate form of government. Yet too little attention is paid to how these institutions operate and impact – or fail to impact – on the daily lives of citizens.

In a new ARI blog series, “NIGERIA: HAVE YOUR SAY”, Nigerians from many different walks of life will reflect on aspects of sub-national government from Borno in the north-east to Lagos in the south-west; and from Sokoto in the north-west to Enugu in the south-east. There will be no overtly self-serving or politically partisan inclusions.

In launching the series, ARI aims to provide a platform that will contribute to a more nuanced understanding of local governance in Nigeria and to draw attention to suggestions for improvement. New submissions will be added regularly in the coming months.

In the introductory blog, Cheta Nwanze argues that the “state of origin” concept should be done away with.

Anyone who has ever tried to move house in Lagos knows that it is back-breaking work. To begin with, there are all sorts of con artists masquerading as agents; and even when you eventually find a place there are agency forms to fill. In most of these, before stating your nationality there is a section for “tribe” and a box for the prospective tenant to declare his or her “state of origin”. I have always tried not to fill the tribe section and I always put Edo – where I was born and grew up – as my state of origin.

The last time I was trying to move, one of the agents took exception to my not declaring my tribe. He said that mine name did not sound like an Edo name, but an Igbo one. It was quite clear that the landlord did not want Igbo tenants. I had heard about this kind of attitude, but it was my first personal experience of it. For me, it is a problem. After all, I am Igbo. It started me thinking harder about the complex issues of nationality versus state of origin versus ethnicity in Nigeria – one of the thorniest issues that we face as a country.

Far too many people have failed to make the leap from identifying themselves as members of their ethnic groups to seeing themselves as Nigerians. The common argument you hear is that Nigeria is an artificial creation and if it disintegrates tomorrow, the tribes would remain. I think that view is an anachronism. What people still clinging to their tribal identity have either forgotten or are not aware of is the truth in the cliché “change is the only constant thing in life”.

A fable and identity

Eight hundred and ten years ago, the people of a small village called Igodomigodo sent a message to the great city of Ife. There was a power vacuum and they needed a king to rule them. The Ooni of Ife’s reply was a strange one. He sent back a louse, saying that if Igodomigodo could return the same louse in three years he would send them a king. One of the high chiefs, Oliha, put the louse in the hair of one of his slaves and instructed the slave not to have a haircut for three years. The (fattened) louse was duly despatched to Ife and an impressed Ooni sent his son, Oranmiyan, to rule Igodomigodo.

Oranmiyan never did rule. Palace intrigues prompted his swift departure from the village. In his annoyance, he named the village Ile Ibinu (“House of Anger”) as he left, a name later corrupted to “Benin”. However his son, Owomika, grew up to become Eweka, the first Oba of Benin. At the time, the villagers still regarded themselves as being the people of Igodomigodo. Over two hundred years later, in the first half of the 15th century, one of Eweka’s descendants, Ewuare, began a conquest of the outlying areas.

By the time Eweka’s great-great grandson, Esigie was sitting on the throne in 1504, the entire region west of today’s Benin City up to today’s Port Novo, eastwards to today’s Ogwashi Uku, northwards to today’s Okpella and south to today’s Warri were paying tribute to the Oba of Benin. The subjects of the empire, especially those who were indigenous to Benin City itself and its immediate outlying towns and villages, considered themselves to be Edo people. An insult to one was an insult to all others. This nationalistic behaviour meant that when the British began their conquest in the late 19th century of the region, their landing at Ughoton was viewed as an attack on the empire and Oba Ovonramwen sent troops to oppose it.

Unlike the Edo to their west, people from the collection of villages most of which were situated to the east of what was to become known as the River Niger were not part of an empire. They were content with living in settled city states, as it were. The only ones amongst them who showed any expansionist tendencies were the people of Arochukwu who began a bid for dominance as a result of the slave trade. The Aros subjugated the communities in their immediate vicinity and on occasion launched slave raids as far north as Nsukka. But unlike the Edo they never attempted to bring the entire region under their control.

When the British came, they faced major opposition in Edo but in Igboland battles were few and far between. In fact, many in Igboland had good reason to celebrate the end of the overlordship of Arochukwu. It was with the arrival of the British that the Igbo identity began to evolve. Since the colonists in time picked Enugu, an “artificial” city that arose on the back of the nascent coal industry, as the capital of the Eastern Region, it became the de facto Igbo capital.

Towards a national identity

At independence in 1960, these identities, like many others, became part of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, now comprising 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory. Each state in Nigeria has its own uniqueness. Stereotyping often depicts life in Kebbi as idyllic and life in Lagos as frenetic, while Kaduna wants to jump ahead and Ebonyi is content to take things nwayo nwayo. But Nigeria’s unitary state only masquerades as a federation. The federal government essentially belongs to no one and as a result many Nigerians are ambivalent when it comes to caring about how the country’s affairs are being governed. This is the root of the current constitutional crisis

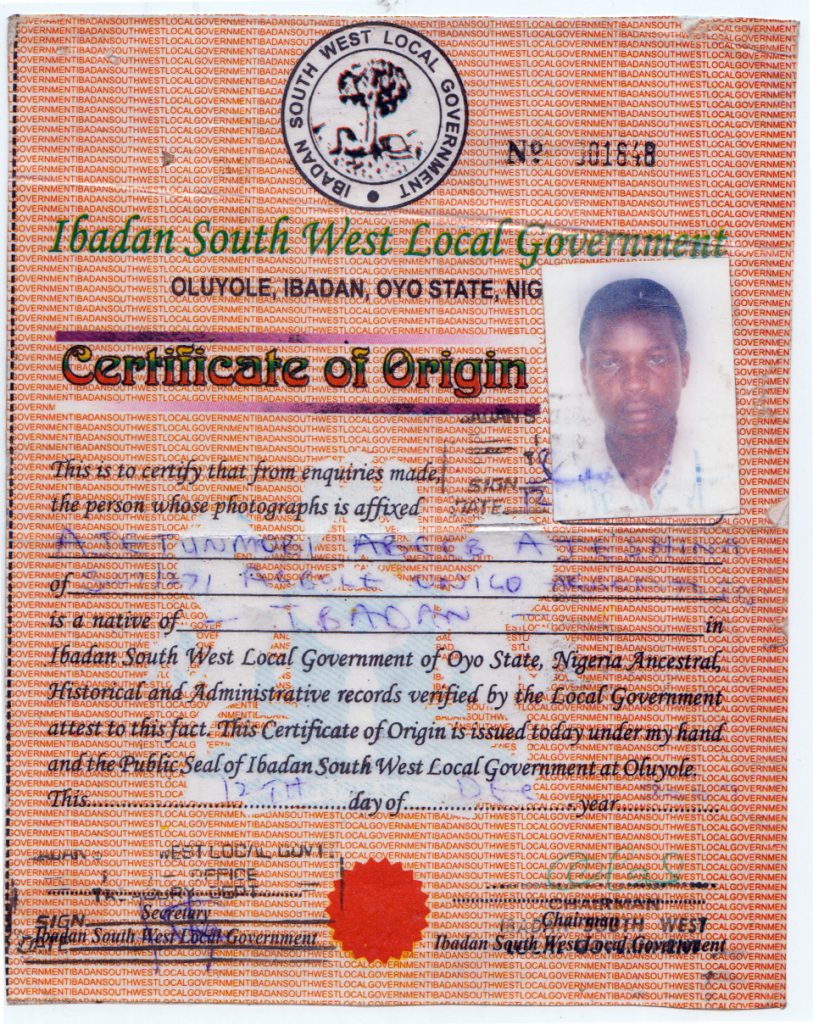

For Nigeria to make progress towards greater unity we have to expunge the “state of origin” concept from the 1999 Constitution. While this does not explicitly mention the phrase “state of origin”, by vesting so much power in the Federal Character Commission and thereby tying citizens to the state of their ancestors the problem is entrenched in the governance system. Although almost everyone knows their ancestry, those who are unable to document it officially face considerable difficulties, both in terms of belonging and in accessing state resources.

For the Nigerian federation to work, Chxta must be able to move from Abia state to Zamfara state and feel at home. Chxta must also be able to aspire to the highest office in the state he chooses to call home. But if Chxta wants to move from Anambra to Yobe, he must be willing to live according to the traditions of the majority population in Yobe. On this point, I see no reason why a majority Muslim state cannot have sha’ria existing side-by-side with Nigerian federal law, provided that it is supplementary to the law of the nation. In turn, the people of Yobe must be willing to accept Chxta as one of their own and give him the right to pursue a decent living. That way, the state and the individual can both profit.

In 1914, the British, by fiat and without consulting the people, created Nigeria by merging the Northern and Southern Nigeria Protectorates. Yet even after 56 years of independence it would appear that Nigerians are still to learn to live with each other. We have not yet accepted that the evolution of national identity takes time and rests on a lot of intermarriage, a lot of resettlement and a lot of infighting. The “state of origin” concept only gets in the way of us doing so.

Cheta Nwanze is lead partner at SBM Intelligence. Prior to joining SBM, he worked in both IT and journalism in Nigeria and the UK. Cheta has had opinion pieces published in Premium Times, The Guardian, Sahara Reporters, Al-Jazeera and Africa is a Country. He tweets @Chxta

If you are interested in writing a piece on some aspect of life in your state, please contact Jamie Hitchen (jamie@africaresearchinstitute.org) who can provide further information. You need not have had any experience of writing articles or blogs. We welcome suggestions from the young, the old, government employees and entrepreneurs, traders and teachers – anyone with an insightful and interesting take on an issue of importance in their state. Please note that contributors are not remunerated.