Flashback to 2007: a few days before Nigerians were to go to the polls, outgoing president Olusegun Obasanjo publicly declared the presidential election to be a “do or die” affair for him and his ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The election was won by the PDP and Obasanjo was replaced by an ailing successor, Musa Yar’Adua. At both presidential and gubernatorial level, the process was condemned as heavily flawed by local and international observers – marred by widespread vote-rigging, ballot stuffing and violence that government security forces were complicit in.

Nine years later little has changed in the nation’s electoral tradition except that the electoral stakes have worsened from “do or die” to “do and die” affairs. This is the case across all three tiers of the federation. For Nigerians, electoral processes are characterised by palpable tension, anxiety and fear.

A new governor, but the same old problems

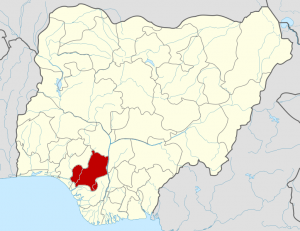

Citizens of Edo state will elect a new governor on 28 September 2016. Edo is one of seven Nigerian states that no longer hold polls concurrently with presidential elections. After defeat in the 2007 vote, current governor, Adams Oshiomhole, successfully challenged and overturned the election results, but the protracted legal battle meant he only assumed office in November 2008. In 2012, he was elected for a second term with 76.8% of the vote. As the 2016 election draws near, divisive rhetoric is escalating. Nineteen political parties will take part, all of which have put forward male candidates, but in reality it is a battle between the All People’s Congress (APC) and PDP. APC candidate Godwin Obaseki is a stooge of Governor Oshiomhole, who will step down as he is barred from running for a third term. Obaseki’s main challenger, Osagie Ize-Iyamu, was a close ally of Oshiomhole and prominent member of the APC before defecting to the PDP in 2014.

In Nigeria, insufficient attention is paid to the processes through which candidates emerge for elections. In Edo, it is alleged, both Obaseki and Ize-Iyamu were handpicked by godfathers and imposed on their respective parties through shambolic conventions where delegates were manipulated and bribed with huge sums of money in exchange for their votes. Obaseki won 64% of delegate votes, whilst Ize-Iyamu gained the nomination after securing 81%. The tragedy of democratic elections in Nigeria is that the system does not allow genuine and morally sound candidates to emerge. At the end of the day, the electorate are left to choose not between lesser and bigger evils, but between two big evils.

Talking about the wrong issues

In the run-up to the Edo contest there is little discussion of each candidate’s economic plans or their blueprint for tackling unemployment, insecurity, epileptic electricity and a comatose health care system. Both sides are busy talking about power, not services; about ruling, not leadership; and about being in control, not setting the agenda for development.

One of the main debates surrounds which ethnic group or clan should produce the next governor and deputy governor. Ahead of 2016 the APC and PDP both chose to zone the governorship slot to Edo South, comprising Benin City and its surrounds, an area that has the highest voting bloc. The parties were correct in their belief that the people will vote for any candidate that hails from their ethnic group, especially in state elections. The understanding is that the best way to ensure attention is given to issues facing your area is to have someone from your tribe in power, as he will use his position to influence decisions favourably. This has certainly been true in the case of Oshiomhole.

Since taking office in 2008, Oshiomhole has used significant sums of state resources to build a new university at Iyamo, his hometown in Edo North. At the same time, the existing state university, Ambrose Alli University in Edo Central, was starved of funds. Visitors to Edo North will also find that most roads in the region have been repaired and new ones constructed. Meanwhile, citizens of Edo Central accuse the state governor of neglecting them and are clamouring to have their own “son” elected in order to enjoy some “development”.

The value of power

In Nigeria the fastest way to become rich is not by becoming an entrepreneur, a thinker or a good person. Gaining political power gives unhindered access to state money. As ARI’s recent briefing note on state governments in Nigeria highlighted, the rewards of governorship are particularly lucrative: “by law, governors in many states receive their salary for life and keep perks from their time in office such as official houses, cars and furniture”.

In a country where legal structures governing land ownership, taxation and private property are weak, and where economic policies are subject to the whim and caprices of the current ruler, having – or being close to – political power is extremely valuable.

The fabled African sense of community, brotherliness or Ubuntu – characterised by the “I am because we are” philosophy – has been replaced with the twin principles of the statist, post-colonial political structure: “‘I am because I have power” and “I have money because I have power”. Unless there is a rapid change in consciousness and political awareness among the vast majority of Edo residents, the political landscape will remain unchanged by this election. Yes, a new governor will be elected but monetised, self-serving politics and the do and die election tradition will prevail. Ordinary citizens will be left to suffer.

Anselm Adodo is Director of Africa Centre for Integral Research and Development, which focuses on new approaches to social, economic and political reform in Africa, based on African culture and world views.