Throughout Africa, reports of national biomedical systems being unable to provide sufficient care for their citizens, especially in rural areas, are increasingly common. In Cameroon, doctor-to-patient ratios and government spending on health are relatively high, although the health system is geographically unbalanced: 40% of doctors practice in the more affluent Centre region, home to just 18% of the population.

The reports of overburdened, underfunded medical systems in Africa are often accompanied by a recommendation for the integration/collaboration/professionalisation of traditional doctors and traditional medicines. It is usually envisaged that such a process entails traditional doctors receiving training in, and then providing, basic biomedical services; and traditional herbal medicines being tested and used within biomedicine.

These widely endorsed proposals for integration may not be realistic or successful when put into practice, as the example of Cameroon demonstrates.

Health care and integration in Cameroon

The 1970s and 1980s witnessed a push to investigate and potentially implement integration of traditional doctors into the national health care system in Cameroon. The central government surveyed and licensed traditional doctors as part of a global strategy, led by the World Health Organization, to provide “Health for All by the Year 2000”. The aim was for traditional doctors to provide basic biomedical services in rural areas.

The survey provided valuable information about traditional medical practices and practitioners, but it did not lead to their incorporation into biomedical institutions. The emphasis on regulation and licensing hindered collaboration; so too did entrenched scepticism regarding the merits and efficacy of traditional medicine.

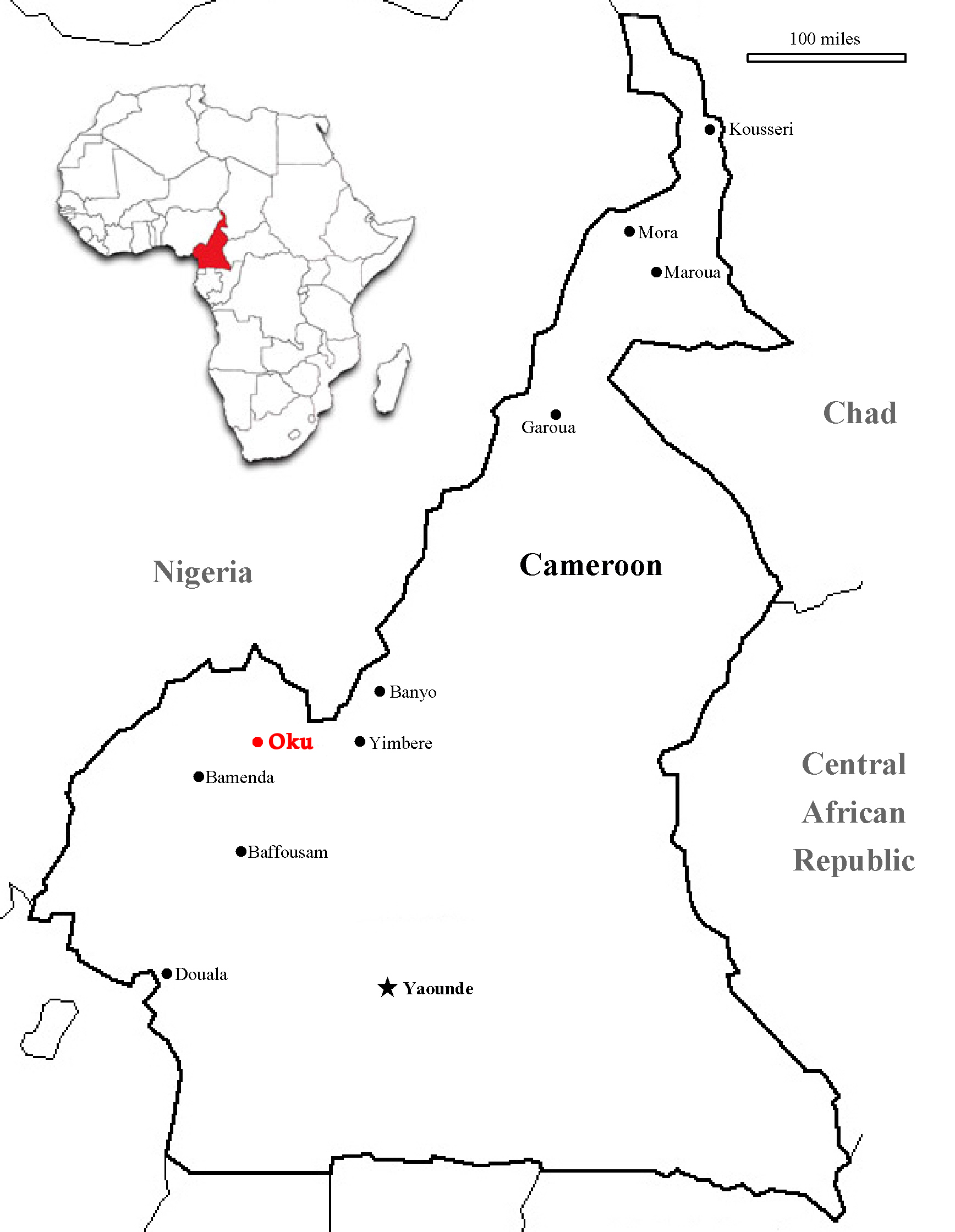

In the 1980s and 1990s, the development of herbal products derived from traditional medicine attracted attention. For example, the bark of Prunus africana, a major ingredient in traditional medicines for fevers and reproductive ailments in the region, was harvested from Oku and other highland chiefdoms for the manufacture of Tadenan (or Pygeum), sold internationally as a treatment for prostate hyperplasia. In addition to causing over-exploitation of forests, the commercialisation of this traditional medicine did not confer any discernible financial or health benefit on local populations.

Despite these past failures, my research in Cameroon has revealed ways in which traditional and biomedicine systems are interacting in an attempt to improve health care.

Comorbidity and informal collaboration between traditional and biomedical doctors

There is a growing prevalence of chronic illnesses such as cancer and diabetes in Cameroon and throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, comorbidity is common, with patients in rural areas suffering from a combination of infectious diseases, non-infectious diseases and other conditions including malnutrition and anemia.

Comorbidity is a substantial challenge for health systems in Africa. It is difficult to diagnose all of the ailments afflicting a patient, just as it is impossible for all but the richest patients to afford lab tests and treatments for a plurality of illnesses. All too often comorbidity leads to patients remaining ill after receiving uncomprehensive medical treatment. This, in turn, results in simultaneous or alternate use of traditional and biomedical systems in an attempt to find a conclusive cure. It is here that innovative collaborations and synergistic care can be observed in Cameroon.

For example, it is now common for traditional doctors in Oku to send their patients to biomedical institutions to undergo diagnostic lab tests. Traditional doctors explain that they do this – often in conjunction with traditional divination procedures – in order to determine what is ailing the patient before commencing a traditional treatment. Henry Nkwan, a traditional doctor, stated: “Now we are living in a modern world. If a healer needs to know where a patient’s madness [for example] comes from, [we] can send the patient to the hospital for lab tests and the results will show what is wrong with the patient.”

Traditional doctor, David Nchinda, is shown here with a fresh harvest of medicinal plants

At times traditional doctors counsel their patients to repeat a diagnostic test to establish how effective their treatment has been. They may also refer their patients to biomedical practitioners for other services. One traditional doctor in Keyon, Oku – David Nchinda – sent a patient suffering from oedema of the abdomen to the local clinic for surgery to drain accumulated fluid. Meanwhile, he continued administering his own extensive traditional treatments to the patient.

Some biomedical doctors have consciously collaborated with traditional doctors. Dr. Eric Nseme, formerly chief medical examiner at the Oku Subdivisional Hospital explained: “I have some of them [traditional doctors] who are in working partnership with the hospital today. Working partnership means… they bring cases to the hospital. We make some biological tests. We try to diagnose and the [patient] goes now to follow the treatment [from a traditional doctor].”

Dr. Nseme had witnessed patients whose ailments he had diagnosed go on to receive successful traditional treatments. Based on his experience in Oku, he felt that patients benefited from traditional medicine in cases where they thought they would not be cured by biomedicine alone. In his words: “People believe strongly in traditional medicine… Because of their belief, they are thinking that their problem is coming from a spiritual action and they think it is only spiritually [i.e. through traditional medicine] that the problem can be solved.”

Mr. Sah, of the Oku Subdivisional Hospital, performs the diagnostic test for malaria

During my research in Oku, mentions arose of biomedical doctors also referring patients to traditional doctors for counsel, or in cases of terminal illness when biomedical treatment options had been exhausted. The research revealed that patients may find traditional medicine particularly appealing in the context of terminal disease since diseases diagnosed as terminal in biomedicine may be considered curable illnesses with existing remedial therapies within traditional medicine.

Meeting the demands of patients

It is not only practitioners who promote co-ordinated health care. More often than not, the patient brings about collaboration by taking medicines from within both medical systems. Patients in Oku frequently seek out particular traditional tea preparations as a way to supplement and complete biomedical treatments. These teas comprise a (sometimes vast) combination of leaves, roots and fruits and are full of vitamins, minerals and, in many cases, multiple medicinal properties. As such, these teas are known to alleviate symptoms that may persist after biomedical treatment; they target infections and underlying conditions not identified or addressed within prior biomedical consultation.

For example, the tea Ntombang is reputed to “add blood”, thus addressing symptoms of weakness, lightheadedness, and fatigue characteristic of illness and post-illness anemia. Henry Nkwan stated that “Ntombang…makes people feel like they’ve had drip [i.e. an intravenous hydration or blood transfusion].”

The interaction and “integration” of traditional medicine and biomedicine can include an array of practices besides the incorporation of traditional doctors and their medicines into biomedicine. Successful collaborations are those in which the traditional doctors maintain their autonomy, are treated with respect, and retain control and protection of their medicinal knowledge and plants.

It is in the best interest of future collaboration, and the continued use of locally available and often more affordable medical treatments, for the stigmatisation of traditional medicine in communications from religious and biomedical sources to be discouraged. Perhaps a dialogue with religious leaders and medical educators could form part of the government’s effort to prioritise health care access for the poor. Wider recognition, exploration and development of the kinds of collaboration between traditional medicine and biomedicine being practised in Cameroon and throughout Africa may provide the most promising starting place for a much-needed expansion of medical services to meet escalating and evolving health care needs.

Dr. Kelly obtained her D.Phil in Social and Cultural Anthropology from the University of Oxford (2014). Her research in Oku, Cameroon commenced in 1999 and has centred on: traditional medicine, ethnobotany, female infertility, children’s ailments (malaria) and chronic illnesses.