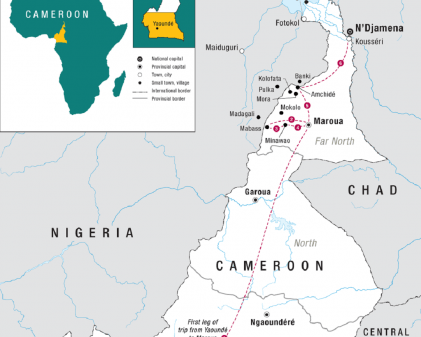

Cameroon has been officially at war against Boko Haram since 2014. Although the jihadist group has been considerably weakened since its apogee in 2014-15, it is not yet defeated – as the mid–2017 increase in suicide attacks demonstrated. In the Far North region, approximately 2,000 civilians and soldiers have been killed, and more than a thousand abducted. The army has killed an estimated 1,500–2,100 Boko Haram fighters and arrested nearly a thousand suspected members.

Boko Haram’s impact is not limited to battle casualties. An internal government report of September 2016, seen by Crisis Group, lays bare the damage to infrastructure. Destroyed or damaged facilities in the three border divisions of Mayo Tsanaga, Mayo Sava and Logone et Chari include more than 40,000 houses, dozens of villages, hundreds of markets, 128 schools and 30 health centres. The total damage is estimated at US$450m.

Credit: International Crisis Group

The Far North was the poorest part of the country before the conflict, with 74% of the four million inhabitants living below the poverty line, compared to a national average of 37.5%. Boko Haram has preyed on the population, looting and burning villages, and extorting protection money. The war has worsened an already precarious economic situation, led to large-scale displacement and put huge additional strain on the disadvantaged population.

A paralysed economy

In addition to the prevailing insecurity, emergency measures put in place by the government after suicide attacks in Maroua in mid-2015 have severely disrupted agriculture, livestock farming, fishing, trade and tourism. Agricultural production in the Far North has fallen by two–thirds: lands in the border regions have been inaccessible for three years, and up to 2016 the cultivation of crops that grow above a certain height – including staples like maize and sorghum – was prohibited for security reasons.

The closure of the border with Nigeria has been disastrous for thousands of small traders, who have been forced to make lengthy and costly detours of 100–200 km on bicycles or motorbikes. The cost of essential imports such as cooking oil, sugar, flour and other processed products from Nigeria has consequently risen, price rises being only partly offset by the declining value of the naira.

Everywhere in the region, movement has been impeded. In 2014, the road connecting the important market town of Kousseri with the southern part of the country was closed for several months. Until 2016, many other heavily used roads could only be passed with military escort. Boats were banned on Lake Chad, the Logone River (at the behest of the Chadian authorities) and other waterways. The impact of the prohibition of motorbikes, imposed to prevent drive-by attacks by Boko Haram, has been devastating for drivers and passengers alike.

Tourism has collapsed. Its stunning landscapes once made the Far North the second-most visited region of Cameroon but, since 2014, European countries and America have advised their citizens against travelling there and Cameroonian tourists have unsurprisingly stayed away. According to the head of the regional tourism office, several hotels and dozens of restaurants have closed down, resulting in the loss of many jobs.

Development needs but emergency assistance

People have shown remarkable resilience and adaptability in the face of the onslaught on their livelihoods, exemplified by hosting refugee and displaced communities. Their response stems from the region’s diverse and interconnected history. In the 1980s, economic specialisation by ethnic groups, such as fishing for the Kotoko, livestock farming for the Choa Arabs, agriculture for the Mafa, was eroded by worsening poverty and desertification. Many were forced to move, broaden their expertise and diversify. Faced with even tougher economic realities, communities have developed varied survival strategies.

Unfortunately, national authorities and international development partners have made little attempt to capitalise on local potential. The danger is that Boko Haram violence reinforces a common perception in Yaoundé, the national capital, of the Far North as a hopeless case, far from “Cameroun utile” (the coastal and central areas that were the main focus for the colonial powers and remain the core of the country’s economy).

While short-term assistance help is certainly needed – both for humanitarian and developmental reasons – a strategy for the long–term revitalisation of the Far North is essential. The government, fixated on security, has done little to stimulate the economy, beyond a few emergency initiatives which have been undermined by insufficient funding and poor implementation. Meanwhile, international development agencies have been preoccupied with the humanitarian response, itself still deficient. With the exception of a few projects run by UNDP, GIZ, the World Bank, USAID and the French Development Agency (AFD), very little attention has been paid to sustainable development.

Towards a “development contract”

Without a longer term strategy to boost employment, small businesses and the informal economy, the Far North will remain vulnerable to Boko Haram – or other “insecurity entrepreneurs”. This presents the authorities with a dilemma. On the one hand, a legitimate fear that Boko Haram will “capture” the informal economy for its own benefit gives rise to the temptation to constrict it through taxation or force. On the other hand, if security measures are not relaxed in appropriate ways, economic activity will remain depressed and people will remain vulnerable to even worse hardship – and recruitment.

To improve the prospects of long-term development and move on from emergency measures, the government and its international partners must think creatively. The population wants greater state involvement and its benefits – roads, public services and jobs. But national and international development planners should not seek to impose their own, potentially restrictive, models. The resilience and adaptability of the local population, and informal cross border trade in particular, are the foundation for the region’s ultimate revival.

Local economic networks, practices and traditions need to be clearly understood and integrated in any long-term plan; and local experts and communities need to be consulted and involved in the whole process from planning to implementation. Women, youth and particularly the most affected and vulnerable communities should be prioritised in a “development contract”. Ideally, this would also dovetail with similar plans drawn up by other countries of the Lake Chad Region, such as the Buhari Development Plan for North-Eastern Nigeria adopted in June 2016.

As the intensity of the conflict in Cameroon’s Far North has been diminishing, a good start point for its revitalisation would be for the government to relax more of the emergency measures adopted in July 2015, where the security situation permits. Since the beginning of 2017, this has occurred, in an informal and low key way, in towns like Maroua, Mokolo and Kousseri. Reopening the border with Nigeria would be a welcome further step.

Hans De Marie Heungoup is Cameroon Analyst at International Crisis Group, the independent conflict-prevention organisation.