This is the first chapter of our 2014 Paper The Mayors, the booklovers, and the citizens: participatory budgeting in Yaounde, Cameroon. It examines how citizens, local mayors and a society of booklovers collaborated to establish participatory budgeting in Yaoundé, despite the weakness of democracy and absence of traditions of participation or public service in Cameroon.

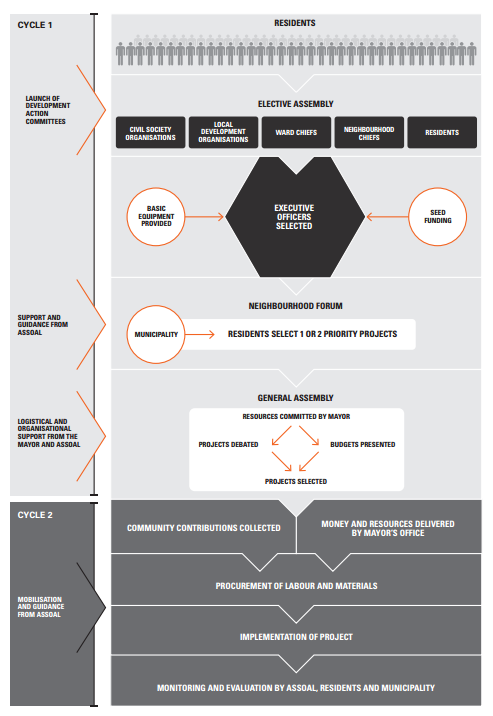

In August 2012, neighbourhood meetings were taking place in three of the seven municipalities in Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital city. In some locations, a new initiative to boost attendance by sending SMS reminders to 50,000 residents appeared to have been successful. While the turnout at most meetings could be counted in tens, not thousands, very few were cancelled due to a lack of interest.

The purpose of the meetings was for residents to debate what basic infrastructure projects their neighbourhoods needed and to agree on the most pressing priorities. The projects selected by vote would subsequently be presented to the mayor by elected neighbourhood representatives. The meetings I witnessed were animated and mediated fairly and competently by a trained external moderator. Majority decisions were accepted with apparent equanimity by those whose proposals had not proved most popular. Final decision-making would be in the hands of the mayor at a competitive public forum. There were insufficient funds available to finance all proposals in any of the municipalities.

Participatory budgeting (PB) involves local authorities and the inhabitants of a municipality, or some other administrative unit, co-operating in determining the allocation of public money. Its objective is to provide an opportunity for citizens to influence decisions about the provision of services and where they will be located. The proportion of the total municipal budget made available through PB for discretionary expenditure on small public works is typically 2–10%. But the will to improve basic services and infrastructure in poor, marginalised neighbourhoods is generally regarded as being more important than the sum of money available.

Read the whole paper The book lovers, the mayors, and the citizens: participatory budgeting in Yaounde, Cameroon

Projects selected by communities might include wells and standpipes, sanitation and sewerage works, street lighting, paving and roads, or housing. An important principle of PB is that communities must themselves contribute – in cash, manpower, materials or land – in order to promote a sense of ownership of any new assets. Construction or implementation of projects should be a joint, monitored endeavour involving neighbourhood representatives and the municipality. If PB is to yield demonstrable benefits and prove sustainable, commitment and trust on the part of all participants are indispensable.

For Jules Dumas Nguebou, co-ordinator of programmes at ASSOAL, the leading civil society organisation promoting the adoption of PB in Cameroon, its potential is considerable:

The introduction of PB in Cameroon, although in its infancy, has allowed for the participation of citizens in decision-making processes which fundamentally affect their lives. It has brought tangible, if modest, improvements. PB can help municipal authorities to engage with the population – the voters – and provide important feedback about development projects and programmes. In instances where this has been effective, PB has contributed to a reduction in corruption in local government.

At the local level, it is easier to bring concrete change to the lives of citizens, easier to have some real impact on local administration and against local corruption, and easier to organise social services to the poor. In a country with a political framework like that of Cameroon, a local approach is a much more effective way of pursuing important socio-economic goals and reducing poverty.

PB is essentially governance for poverty reduction. It can also help to foster democracy – most importantly in countries that are, or have been, dictatorships. It gives people the opportunity to participate in administration and press for local developments which will improve their lives, including better access to basic services and housing.

For progressive local government leaders, PB offers an opportunity to increase the impact of very limited financial resources by aligning policymaking with local needs. Yvette Claudine Ngono, Mayor of Yaoundé V, one of the capital’s seven municipalities, explains why this prompted her to adopt PB:

We launched PB in Yaoundé V in June 2012. PB empowers local government to do more – and to do what people want. We have undertaken to allocate 10–15% of the total municipal budget to PB. As it involves working with all neighbourhoods in the municipality on equal terms we hope to avoid being accused of favouritism. Of course there will be some suspicions about what we are up to.

Before the introduction of PB, the mayor’s office used to take all decisions regarding the implementation of projects in a particular neighbourhood. People were not so happy with that. They felt that their priorities were not taken into account. For example, the town hall might build a new road when the top priority for the residents was a new water point.

The best way to make people more satisfied with local government is to involve them in the budget. We had to find a way to ensure that residents came together, discussed their problems and chose their own development priorities which were then presented to the mayor’s office.

If residents are involved in identifying development priorities and solutions, they are likely to be more involved in ensuring that a project is carried out properly. When plans for a new road or water point are agreed, local people are able to say, “that’s our project, we don’t want it to fail or be put in the wrong place”. The mayor’s office also benefits from knowing that money has been channelled to meet the requirements of the community, not just for the benefit of a few.

PB represents a new social contract between the municipality and the population. It aims to place the aspirations of citizens at the forefront of local development.

Although PB is most commonly associated with Brazil and other South American countries, the process had been practised in as many as 1,500 states, cities, towns and rural municipalities worldwide by 2010 (1). It has been depicted as a shining example of the merits of “grassroots democracy” involving a mobilisation of citizens which can be replicated for other purposes – for example, to resist eviction. It has also been hailed as “one of the most significant innovations for increasing citizen participation and local government accountability” (2).

Caution is required when confronted by the bolder claims. There are plenty of documented examples of PB delivering basic infrastructure to poor neighbourhoods which would certainly not have secured these essential improvements through any other means, as in Cameroon. There is also evidence of PB helping to improve financial management, the image of local administration and revenue collection. But PB is not a developmental “silver bullet” which lends itself to easy distillation in a blueprint.

The PB process and outcomes differ location by location. This is inevitable given a plethora of variables, including the motives and objectives of the individuals and groups involved, the degree of participation and the extent to which it is genuinely collaborative, the scope of the projects or measures under discussion and the available resources. Literacy levels and history can be equally influential. While certain fundamental principles are typically observed in examples of PB deemed successful, their adoption does not guarantee “success”. Even in Brazil, the birthplace of PB, its record is not unalloyed – although the positive developmental outcomes secured by PB in that country are arguably unrivalled.

Civil society organisations have led the introduction of PB to Cameroon. It has been no easy task. As Achille Noupeou of ASSOAL says in this paper, “democracy in Cameroon is weak and there is no tradition of participation”. Mayors have for the most part been reticent or obstructive. Implementation of projects is often fraught with difficulty. But after a decade of considerable effort on the part of its proponents inside the country and elsewhere, the process appears to be firmly established.