Yoweri Kaguta Museveni was confirmed as the winner of Uganda’s presidential election for a fifth consecutive time on 20 February 2016. However, if the president is to stay in office beyond the next set of elections in 2021 he will have to overcome a constitutional impediment. Article 102 (b) of Uganda’s 1995 Constitution states that “a person is not qualified for election as President unless that person is not less than thirty-five years and not more than seventy-five years of age”. President Museveni will be 76 in 2021. But in the last year, Museveni, indirectly and from a distance, has been testing out strategies to either keep himself in power or anoint a successor.

Born again?

In December 2016, Justice Steven Kavuma, Uganda’s second most senior judge was rumoured, though this has been denied by Uganda’s judicial authorities, to have sworn an affidavit that he was in fact four years younger than his official age. At 69, Kavuma appeared to have found a new lease of life, just as his retirement age of 70 loomed. His announcement drew much hilarity on Ugandan social media, but was there an ulterior motive for his actions?

Kavuma, a founder member of the National Resistance Movement (NRM), served as State Minister for Defence in the early 2000s and was described as “hugely partisan” by a former Supreme Court judge. The process behind his appointment as Deputy Chief Justice in 2015 was challenged in the courts over its legality. “There is no doubt he enjoys the confidence of Museveni”, Nicholas Opiyo, a Kampala-based political analyst and human rights lawyer, told ARI. Could he therefore have been testing the water for the president? Museveni’s official birthday is 15 September 1944 but given his well-documented upbringing to rural, illiterate parents, the date was estimated by reference to local historical events. Museveni only needs to be one year younger, not four, to stand again in 2021.

The idea of altering one’s age is not as surprising as it might sound according to Opiyo, who notes that “the practice is commonplace among civil servants who do not want to retire upon clocking up their mandatory retirement age”. A point reinforced by a letter dated 6 February 2017 from the Ministry of Public Service (MPS), which indicated that “many requests” had been made by officers to change their dates of birth, particularly those coming up to retirement. For now the MPS has been clear that the dates declared at the time of initial appointment will be used, but Museveni will undoubtedly be watching what unfolds with interest.

A repeat performance

Elsewhere, the wheels are already in motion for a tried and tested approach. In August 2016, a private member’s bill was presented to parliament by NRM MP Robert Ssekitooleko. The bill, which was subsequently thrown out by the Speaker, Rebecca Kadaga, without being debated, proposed the raising of retirement ages for judges and life tenures for members of the electoral commission. “It was widely, and correctly, perceived as a first step towards undermining and eventually amending Article 102 (b) of the Constitution to remove the presidential age limit”, wrote Dr Busingye Kabumba, a constitutional law expert at Makerere University – a presumption denied by Ssekitooleko.

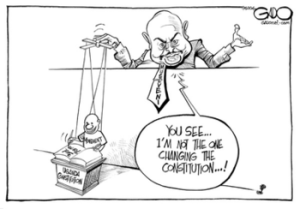

Uganda has “history” of such shenanigans. After the presidential elections in 2001, Museveni faced a constitutional impediment to re-election: the country’s two-term presidential limit would prevent him from standing again in 2006. A sustained and successful parliamentary push for constitutional reform ensued, one from which Museveni consistently distanced himself publically but was widely considered to be directing behind the scenes.

The removal of term-limits was passed by parliament in 2005 alongside the reintroduction of multi-party politics, the passage of the legislation allegedly eased by sizeable incentives to vote in favour of the reforms. Museveni remained in charge.

In Uganda’s 10th parliament the ruling party has the two-thirds majority – excluding NRM-leaning independents – required for constitutional amendments. Even outspoken critics, like Rebecca Kadaga, are unlikely to oppose what Museveni wants. According to Nicholas Opiyo, “she is combative on soft issues, and for the purpose of raising her political capital when it benefits her, but in matters crucial to the president, she has always given in”. A trade-off that sees the removal of age limits coupled with the reintroduction of term limits (with Museveni starting afresh) is a possible approach, and one that would deflect criticism at home and abroad.

Democracy in a different form

The removal of age limits might not be the only change to Uganda’s political system ahead of elections in 2021. With the NRM so dominant in the legislature – the main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), holds less than 10% of seats – Uganda might look to move towards a new democratic model. “I expect the next move for the NRM will be to immunise the presidency from adult suffrage and make ascendancy to the position the choice of parliament,” political analyst Angelo Izama told ARI. If this succeeded, the NRM would all but guarantee that its chosen candidate would be the president and remove any risk of losing out in presidential polls, which historically have produced closer results than those at the parliamentary level. Museveni would still require a resolution to his age-limit conundrum if he wants to remain in charge, but a system where the president is indirectly elected could also open the door further to family succession.

Family planning

A handover of power from Museveni to his son Muhoozi Kainerugaba has long been mooted in Ugandan political circles. Talk of the “Muhoozi project” was revived in mid-January 2017 by a reshuffle in the defence sector that saw several senior “historicals” replaced by military officers of Kainerugaba’s generation. The president’s son moved from being the head of Special Forces Command to State House, where he will serve as a special presidential advisor for special operations – a move that suggests Muhoozi is being prepared for the political and administrative rigours of the presidency. Anna Reuss, a Kampala-based political and security analyst, does not believe there is a fixed plan, but acknowledges that “without doubt he [Museveni] is positioning his son, and other family members, in anticipation of a possible succession”.

If not his son, could Museveni’s wife be the next president? Izama believes so. “Janet Museveni is second to her husband when it comes to political experience, has served as a two-term MP and is a long-serving member of the cabinet. She is also a force in the NRM party and instrumental in state-business relations”. If the system is changed before 2021, “a more direct and less controversial route will open for Janet Museveni”. By keeping the presidency within the family, Museveni would also be able to maintain a degree of control, and use his patronage networks even if he were officially out of office.

How, not if

Museveni has not publically commented on his future but a close look at the political manoeuvrings since his re-election in 2016, and even before, indicate that he is already trying to find a way to extend his time at the helm into a fourth decade. “Many will not support another term”, says social media commentator Grace Natabaalo, but at the same time the majority of Ugandans will not be surprised to see Museveni, or an immediate family member, confirmed as president in 2021. The more pertinent question, and the one to watch, is how they go about getting there.