- Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy where the monarch, currently King Letsie III, has no executive or legislative powers

- The prime minister is the leader of the majority party or coalition in parliament

- Lesotho has a mixed-member proportional electoral system. 120 seats in parliament are filled by 80 MPs directly elected through a first-past-the-post system and 40 MPs whose seats are allocated to political parties to reflect their share of the national vote

- The term of parliament is five years, but the vote on 3 June 2017 will be Lesotho’s third general election since 2012

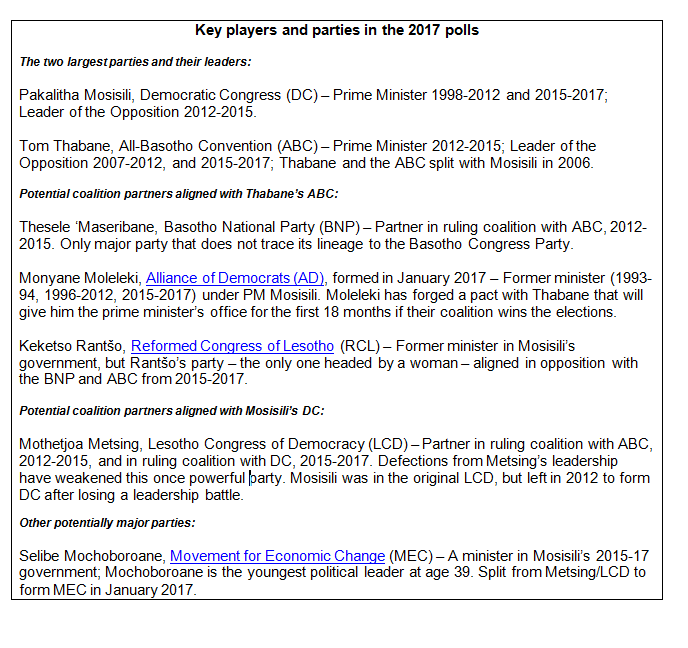

- At least 25 political parties are expected to contest the polls with the two main political parties the Democratic Congress (DC) and the All-Basotho Convention (ABC)

The 2017 elections in Lesotho – the third general election in five years – are a referendum on the rule of Pakalitha Mosisili. Having served as prime minister from 1998-2012 and again from 2015-2017, Mosisili has earned a reputation as a political survivor.

While the presence of Mosisili at the apex of Lesotho’s politics has been a constant for decades, the party structures around him have not been so durable. Mosisili has led three different parties since 1998, all of which are offshoots or splinters of the Basotho Congress Party (BCP), Lesotho’s first political party, founded in 1952. In fact almost all major parties trace their lineage to the BCP with policy differences playing second fiddle to personalities in the country’s politics.

After achieving independence in 1966, Lesotho had a short period of multi-party democracy until 1970 which was then followed by 16 years of autocratic one-party rule. In 1986, the military took power and ruled until Lesotho returned to multi-party democracy in 1993. It is the view of Khabele Matlosa that “Lesotho’s entire political history is marked by incessant and protracted conflicts” between parties and among politicians.

Lesotho has never experienced major violence on election day, but losing parties have often protested in the streets following the announcement of results. In 1998, unrest prompted Mosisili to ask for military intervention from neighbouring states under the aegis of the Southern African Development Community. This led to rioting, the death of at least 60 people, and the gutting of central business districts in Lesotho’s largest towns. Similar protests in 2007, albeit without the same level of violence or military intervention, forced a streamlining of the mixed-member proportional system. Previously voters had the ability to split their vote, choosing a constituency candidate and then a different party on the same ballot. After reforms, the vote cast for a constituency candidate also signified the voter’s party preference for the proportional representation seats. The post-2007 changes and the proliferation of parties have necessitated coalition governments from 2012, as no one party has been strong enough to gain an absolute majority.

The outcome of the 2012 election marked not only Lesotho’s first coalition government, but also the first peaceful handover of power. However, coalition governance has been increasingly unstable as neither the 2012 nor 2015 alliances came close to completing five-year terms.

Prime Minister Tom Thabane’s 2012 five-party coalition, led by the ABC, fell apart in mid-2014 due to conflicts between coalition leaders and disagreements about security sector reform. Violence erupted when Thabane attempted to replace the head of the Lesotho Defense Force (LDF), Lt. General Kamoli, widely seen as a Mosisili sympathiser, with Lt. General Mahao, regarded as more sympathetic to Thabane’s ABC. Thabane fled to South Africa in late August 2014 following an attempt on his life. When Mosisili won the resulting February 2015 elections, he promptly reinstated Kamoli as head of the LDF; in June, Mahao was assassinated by LDF soldiers seeking to arrest him. Other high-profile figures have also faced threats and violence.

Mosisili’s return to the prime minister’s office has been a relatively short one. The seven-party coalition he led to victory in 2015 succumbed to infighting in late 2016 and by March 2017 he had lost a no confidence vote in parliament that precipitated the current election campaign.

Basotho are increasingly disillusioned by politics and politicians. In the multi-party era the number of MPs has grown from 65 to 120, while the number of cabinet ministers has doubled from 12 to 28. Top government officials from virtually every party have faced allegations of corruption, but few of the cases have resulted in convictions.

In addition to the perception that top officials are raiding the public coffers with impunity, Basotho blame the “churn” of administrations for a lack of governance and the absence of an effective strategy to address the pressing problems of poverty, the HIV/AIDS epidemic and famine conditions or to diversify the economy. Perhaps this explains why voter turnout has dropped from over 70% in 1993 to less than 50% in 2015. The challenge for the next government will be finding a way to build a coalition strong enough to survive the five-year term of parliament, establish trust in the efficacy of government and deliver improved basic services for Lesotho’s two million citizens.

Dr. John Aerni-Flessner teaches at Michigan State University (USA). He researches and writes on the history of development and independence in Lesotho and his book “The Desire for Development: Foreign Assistance, Independence, and Dreams for the Nation in Lesotho” is due for release in 2018. He tweets @LesothoJohn

Deiv Rakojoana is an undergraduate student at Michigan State University where he is a MasterCard Scholar majoring in actuarial science. He is from Matelile, Lesotho.

Featured image: By kind permission of Lesotho Times https://lestimes.com/final-elections-tally-announced/