The achievements of successive Somaliland governments in building legitimacy and conducting elections have attracted widespread praise. While the near future will present substantial challenges to the durability of past successes, a close analysis shows that Somaliland offers a great many useful lessons about how to build a Somali nation state. An established, discursive system of consensus-based political participation is as important as democratisation through elections. This system is inevitably imperfect, but it has played a key role in securing broad, though qualified, acceptance of state institutions.

A resurgence of optimism in southern Somalia has diverted attention from more sustained, if less spectacular, political accommodations negotiated in Somaliland and elsewhere in the Somali Horn of Africa. Mundane lessons learned in these territories have once again been relegated to the margins. International participants and elite partners in Mogadishu, Nairobi, Washington and London are absorbed by Somali realpolitik and the apparent progress of a grand technocratic exercise in state-building. It is imperative that those wishing to support continued political development in Somaliland and the region pay greater heed to the historical and cultural context in which it is occurring.

Michael Walls is a senior lecturer at the Development Planning Unit at University College London. He co-organised international election observation missions in Somaliland in 2005, 2010 and 2012 and has written extensively about Somaliland, Puntland and Somalia.

Increasing numbers of non-Somalis are taking notice of Somaliland. In part, this has come about through involvement with, or awareness of, events such as the International Book Fair in Hargeysa, capital of the internationally unrecognised republic. An essential ingredient has been the support of businesses and non-Somali donors for one of the most vibrant cultural events in East Africa. Their contributions make it possible to stage the festival annually – and for free. Huge crowds are drawn, none more so than for the recitals of the renowned Somali poet Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame “Hadraawi”. The Somali Horn of Africa is one of the few places where a poet is able to attain the cultural status elsewhere reserved for rock stars and footballers.

The festival and a new Somali Cultural Centre in Hargeysa are not simply indications of cultural tolerance and vibrancy. In the eyes of many Somalilanders and visitors their success is representative of the dynamic and stable political environment in Somaliland.

There is a strong temptation to

romanticise Somaliland’s stability

International perceptions of Somaliland are usually influenced by – or contrasted with – the ebbs and flows of political dysfunction in southern Somalia. Since the start of 2014, two major military offensives from AMISOM, the African Union force in Somalia, have pushed militant Islamist group al-Shabaab out of all major towns in the south. A US drone attack on September 1st killed the group’s leader, Ahmed Abdi “Godane”. These events have fuelled hope that the government in Muqdisho (Mogadishu) can consolidate its position and start to build the legitimacy its predecessors in the past two decades so sorely lacked. The political challenges remain daunting – and changeable. Military advances do not easily translate into social or political stability.

Amongst those who do retain an interest in the northern Somali Horn, there is a strong temptation to romanticise Somaliland’s stability – built, as it has been for more than two decades, on a deep popular commitment to the avoidance of violence. This narrative glosses over numerous difficulties and shortcomings. Somaliland’s relative success is not unalloyed. Politics is as riven by clan patronage and division as it has ever been. Major challenges lie ahead in registering voters, holding parliamentary and presidential elections, and determining an electoral system for the upper house or Guurti. Women and minority groups are excluded from most formal political participation apart from voting, and some Somalilanders are growing increasingly disillusioned with a secessionist “project” that remains incomplete and fragile.

No society can sustain the high hopes of those who prefer to see only the positive. One of the key failings of many observers, both Somali and foreign, has been a cavalier willingness to adopt rhetoric that embraces only those aspects of Somali history and culture that either add conveniently to a narrative of unique success and stability, or are seemingly evidence of the binary opposite – chaos and disorder. If we are to offer effective support to Somalis committed to building a reasonably inclusive and prosperous future in the Horn, it is vital that we recognise both the challenges and the foundations on which such success is built.

No society can sustain the high hopes of

those who prefer to see only the positive

Politics is always a messy business, but it remains essential despite its persistent failure to satisfy idealistic – or simply unrealistic – yearnings. Building on success tends to be slow, painstaking, erratic and unpredictable. Of these characteristics, only the last two are applicable to the charged dynamism and breakneck speed of political change in southern Somalia. In Somaliland’s case, there is a tendency to depict the territory’s political trajectory as having started in earnest in 1991. This reading takes the fall of General Mohamed Siyaad Barre’s government in Muqdisho as the starting point, with that regime’s egregious abuse of human rights, and most particularly the wholesale destruction of Somaliland’s two biggest cities, as the prima facie justification for the unilateral restoration of the sovereignty that Somaliland enjoyed for five days in 1960.

While each of these facts about Somaliland is correct, and the brutality of the Siyaad Barre regime genuinely horrific, collectively they tell only half the story. Importantly, selective and simplistic historicising does not fundamentally challenge one of the key tropes used to describe Somali political development: that of a people “addicted to congenital egalitarian anarchy”.1 In leaving that presumption somehow unchallenged, Somaliland is presented as exceptional rather than as the latest example of Somali political stability grounded in compromise, conflict and accommodation in the context of a complex set of socio-cultural institutions.

For adherents to this incomplete narrative, Somaliland is remarkable as the first Somali territory to establish a state that is widely accepted as providing, in principle and practice, approximately legitimate democratic government evidenced, in particular, by periodic and largely successful elections. Conversely, sceptics castigate the territory for failing to meet the exacting standards of the perfectly representative state. Dissatisfaction amongst some regarding its legitimacy is advanced as proof of the argument.

Somaliland’s progress has been impressive in many ways. Successive governments in Hargeysa have had to build legitimacy through a series of clan-based conferences held since late 1990. Those governments gradually consolidated their hold on power, but remained sufficiently weak that each needed to secure the support of a substantial portion of the population in order to remain in office. Elections for local councils have been held twice (in 2002 and 2012), as has a popular vote for the president (in 2003 and 2010) and for parliamentary seats (in 2005). One of the presidential elections which resulted in defeat for the incumbent by the narrowest of margins was followed by a peaceful handover of power within the constitutionally stipulated timeframe.2

There were snags with some of these elections. The local council election in 2012, for example, was accompanied by widespread multiple and underage voting.3 But each achieved the objective of providing a mechanism for political contestation in an environment that was largely peaceful. That is a major achievement by any standard. The shortcoming of the exceptionalist narrative is not that Somaliland’s progress is disputed. It lies in misapprehensions about the political process itself and the common inclination to equate the term “democratisation” with elections.

Somali society is conspicuously democratic. Adult Somali males are used to a consensus-based system that allows them full participation in decision-making on all key issues. That system is both highly inclusive – for men – and slow and cumbersome. It is not dissimilar to the type of discursive democracy practised in the city states of ancient Athens. While this form of political participation is rightly criticised for excluding women, and for being crisis driven – it takes a crisis to get everyone together and focused on the problem at hand – it cannot reasonably be described as undemocratic. Unless, of course, our definition of democracy is so idealised as to apply only when all problems of exclusion have first been resolved.

Somaliland’s laudable success is

not one of democratisation at all

In fact, Somaliland’s laudable success is not one of democratisation at all. It is one in which most adult males are being asked to relinquish some of their traditional right to participate in decision-making to allow for a system of representation that permits greater responsiveness and speed, while also holding out the possibility of meaningful inclusion of women and of clan groups who have customarily been excluded. This process is not unnecessary or undesirable. If Somalis are to operate effectively in a globally connected world of nation states, multinational corporations and powerful international lobbies and agencies, they need a system of representative politics that confers the agility and strength to negotiate and participate effectively. If the benefits of engagement with the institutions and representatives of international trade and finance are to be shared reasonably equitably, then it is also vital that inclusive politics provides opportunities for Somali citizens to select their representatives – and remove those who are ineffective.

While elections are therefore instrumentally important, so is an understanding of the established, discursive system of democracy. This helps to explain why it has been very hard to find a way for Somali women, so vigorously active in business and all other spheres of Somali life, to participate fully in politics. It also explains why Somalilanders, no less than other Somalis, are quick to become disillusioned with their politicians. People whom they would once have called to account frequently are now installed in office for five years at a time – or longer when inevitable electoral extensions occur.

In one of the key Somaliland peace conferences – that held in Booraame (Borama) town in 1993 – the chair was noted for urging delegates that “voting is fighting; let’s opt for consensus”.4 For many Somalis, consensus-based politics remains the baseline that informs often unspoken understandings of the ideal nature of democracy. It is unsurprising that the representative politics of the nation state – internationally recognised or not – frequently falls far short of that standard.

A highly selective application of history is also deployed by sceptics to justify the view that Somalis are ill equipped to operate within the confines set by a system of state. Somaliland has achieved a great deal in consolidating governmental institutions that enjoy broad, if qualified, support. Yet it is not the first successful Somali state, and it is incorrect to view Somali society as naturally inclined to anarchy or chaos.

Throughout the past millennium, the Somali Horn of Africa has had vibrant trading ports that periodically spawned or supported systems of government. By the mid-14th century, there were a number of successful and stable trading cities on the long Somali coast, marking the start of a period of at least 200 years of considerable prosperity. One account identifies at least 20 such towns on the Gulf of Aden coast and in the immediate northern hinterland alone.5

Several notable empires were founded on the wealth of coastal trading centres. In the north, the Walashma dynasty built the powerful and long-lived Adal Sultanate, with Seylac its commercial heart and a settlement close to Harar, in today’s eastern Ethiopia, its political centre. Although the sultanate was identified primarily as a Muslim rather than a Somali empire, there is little doubt that Somalis comprised a significant proportion of its population. The 16th-century Adal military leader Ahmed Ibrahim al-Ghazi “Gurey” is still revered amongst many Somalis as the first great Somali nationalist.

It is incorrect to view Somali society as naturally inclined to anarchy or chaos

It is certain, despite a dearth of authoritative documentation of the period, that the Adal Sultanate enjoyed great wealth and considerable territorial control for at least three centuries. Initially it lived at peace with its highland Ethiopian neighbours, with whom it enjoyed extensive trading links, but the relationship grew tense as both sides developed aggressive territorial ambitions. A long period of intermittent trade links and conflict saw huge territorial fluctuations as the Adal Sultanate seized or lost ground to successive highland rulers. Only when the Ethiopian emperor Galawdewos secured the support of the Portuguese, as “fellow Christians”, against Ahmed Gury, who received some backing from the Ottoman empire in what was explicitly framed by both sides as a struggle between Islamic and Christian armies, did the balance of power alter decisively. The Adal forces were roundly defeated on the shores of Lake Tana in 1542, forcing the sultanate into a period of terminal decline.

The Adal Sultanate was one of the most famous of early Somali states, but by no means the only one. The Ajuuraan and Geledi Sultanates in southern Somalia are other prominent examples of distinctively or predominantly Somali governance enduring over long periods of time.

Somaliland enjoys neither the territorial expanse nor the longevity of most of the earlier Somali states. Its uniqueness therefore lies not in its novelty as a resilient Somali state, nor in its democracy, but in its success in building a durable and broadly representative system of government within the borders of a contemporary nation state.

During the colonial era in the 20th century, Somali “states” did not allow the involvement of Somalis in governance. Colonial territories could not by any stretch be described as Somali nation states. The representative democracy ushered in by independence in 1960 and the exuberance of reunification of the British Somaliland Protectorate and Somalia Italiana was lively and vital. It was also chaotic and riven by clan division and dispute. The first attempted coup occurred 18 months later. A mere nine years on, Siyaad Barre’s coup was greeted with relief by a population already disillusioned by the winner-takes-all nature of elections and representative politics.

Siyaad Barre’s government began with a surge of reforming zeal. Clans were symbolically abolished and women were encouraged to play a full part in politics. Again, dissatisfaction followed in short order and, in an effort to retain power, the general was forced to exploit the very clan affiliations he had denounced. Desperate to keep his government in place, in 1977–8 he used a war against Ethiopia to rally his population. Defeat left him with few other options, and he steadily lost power even as he resorted to increasingly brutal repression in an effort to retain it. The insurrection that finally ended his rule started not in Somaliland, but amongst the Majerteen of what is now Puntland.

This series of events underscores the point that while Somaliland is not the first successful Somali state, and did not introduce democratisation to the region, it is the first successfully to combine electoral democracy with nation state government. That is no mean feat, albeit neither the unqualified success nor unacceptable imposition of centralised and clan-based hegemony that are the dichotomous opposites frequently suggested by observers.

The establishment of any nation state is inevitably accompanied by debate and dissatisfaction over critical issues such as citizenship. Not all who reside within a state’s borders will be happy to be regarded as citizens. In some areas of what was once British Somaliland, particularly the easternmost, a significant proportion of the population is emphatically unwilling to be classified as Somaliland citizens. This is certainly not a trivial objection, and it remains to be seen how it will be resolved. But it barely detracts from the importance of Somaliland’s success in other respects.

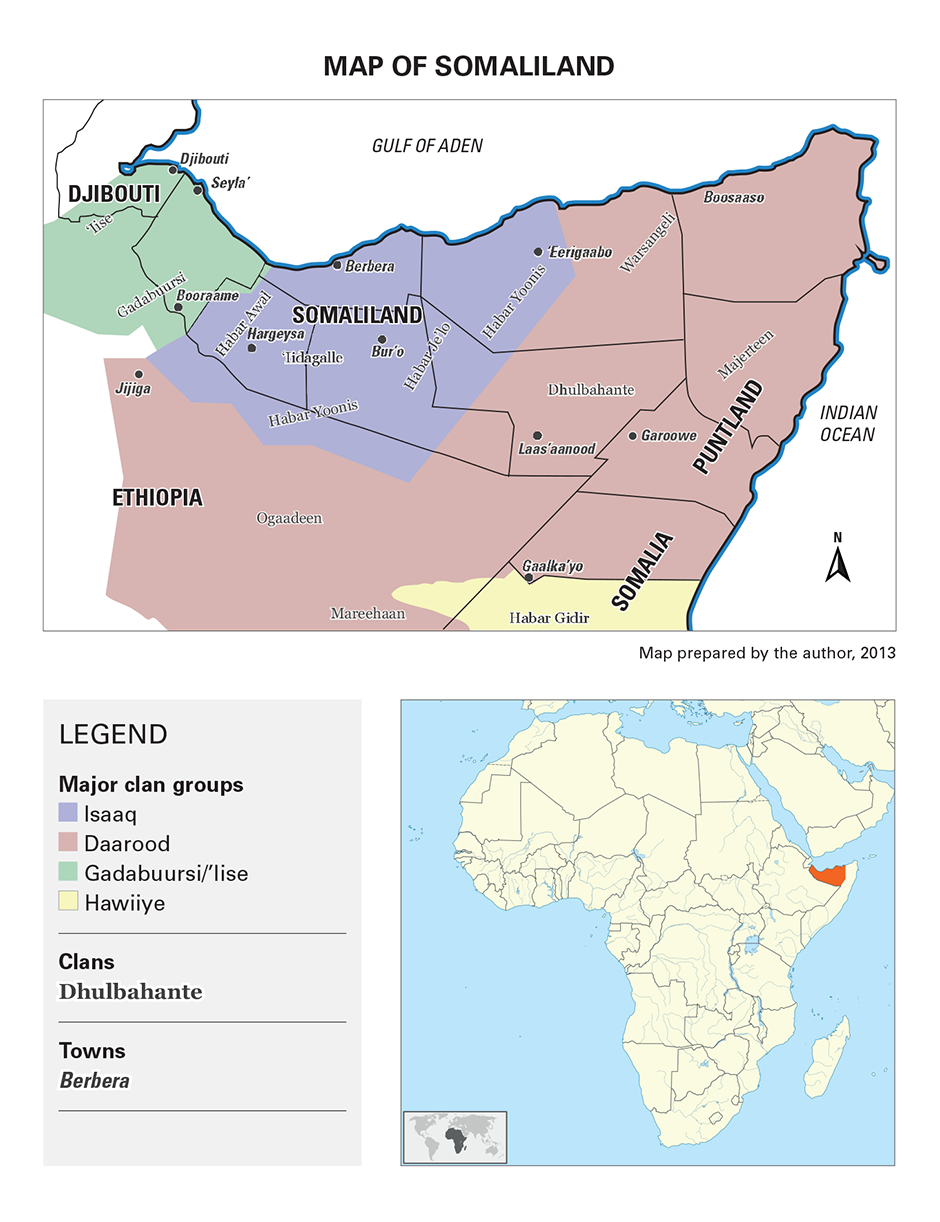

Often derided by critics as a one-clan state, Somaliland is in fact far from that. Although dominated by the large Isaaq clan, this is a clan grouping rather than a single, united lineage. The socio-political system requires support from a number of non-Isaaq clans: for example to bolster constituencies within the divided Isaaq group. Indeed, it was when the Isaaq clans started fighting each other in the early 1990s, once the unifying spectre of the Muqdisho autocracy had vanished, that many other clans gained confidence that Somaliland would not turn out to be an Isaaq hegemony.

If Somaliland’s transition is not one of democratisation, then, but of progression from a patriarchal, discursive democracy to a more inclusive, representative one, that is a transition which could usefully be replicated elsewhere in the region. It is precisely what is currently being negotiated in Puntland, albeit with less success to date. Southern Somalis too are being urged in a similar direction by a heavily invested group of international donors, diplomats and major NGOs.

There is little hope that Puntland will achieve a planned return to electoral politics, following the cancellation of its first popular election – for local council representatives – in mid-2013, unless there is a greater understanding of precisely the transition that is required. There is even less prospect that the ambitious roadmap for the south, which anticipates a constitutional referendum in 2015 followed by full elections in 2016, will succeed in the absence of a more nuanced understanding.

“Federalism” means so many wildly divergent

things to Somalis and non-Somalis alike that it is in effect a meaningless term

Many Somali observers have for years been calling for a return to the sort of local peace-building that worked so well in Somaliland. That process does not necessarily need to replace completely the Muqdisho-centred efforts that have dominated for some time. But the ejection of al-Shabaab from most southern Somali towns and villages provides a real opportunity to transfer some of the ample investment in top-down federal reconstruction to a more localised reconciliation process that allows Somalis throughout Somalia to make the critical decisions about their political future. If the rhetoric from donors about providing support for “Somali-led solutions” is to carry any meaning, it is in precisely this kind of shift.

The difficulty is that this approach will be slow and the results unpredictable – as has been the case in Somaliland. However, without the kinds of local agreements generated by such a process, there is little hope that the always heated and often hysterical debates on federalism and elections will lead to the establishment of durable political systems.

“Federalism” means so many wildly divergent things to Somalis and non-Somalis alike that it is in effect a meaningless term. Puntland’s leaders argue for a version that accords so much autonomy to the constituent parts of the Somali state they hope even Somaliland might be tempted back into the fold.6 Their federal Somalia would look more like a multi-state free trade zone than a single nation. President Hassan Sheikh, meanwhile, has modified his centralising inclinations only slightly, still preferring a far stronger Muqdisho government than many outside the capital are willing to countenance.

If it is to be peaceable and to consolidate progress, Somaliland’s own future will require agreement on some deeply contentious issues. Parliamentary elections are five years late, and now scheduled to be held in the middle of 2015 – at which stage a presidential election is also due. Before any elections can take place, a much delayed process of registering voters must be completed in tandem with a civil registration. The last attempt at voter registration, in 2008-9, was so deeply divisive that it brought the country to the brink of conflict.7

If we bear in mind the transition that Somaliland is making, it is not surprising that it has proved extremely difficult to count voters. The last Somali census was conducted in the final years of Siyaad Barre’s regime, and so threatened to upset the balance of clan power that the results were never released. The Somaliland count carried the same risk of endangering established agreements on clan representation, and it is inevitable that a new effort at registration will be fraught with similar dangers. It is possible that the experience of the 2012 local elections – which prompted widespread recognition that the lack of an electoral register was a key factor in enabling multiple voting on a massive scale – has focused minds in a way that will permit the exercise to be conducted without provoking a crisis this time round. But caution, patience and sensitivity aplenty will be required.

Somaliland’s own future will require agreement on some deeply contentious issues

The situation in the east of Somaliland also seems to be heading steadily towards some sort of denouement. In the areas around Buuhoodle town and throughout most of Sool region, the competition between Somaliland, Puntland and the nascent, Dhulbahante-based regional state, Khaatumo, is becoming increasingly intense. To date, a systematised ambiguity has operated in which each of the interested parties has simultaneously laid claim to the area and operated more or less as though that claim had substance. It is not inconceivable that this ambiguity could be maintained, but it seems less and less likely. For one thing, there are hopes that commercial quantities of oil will be found in the Nugaal Valley, which runs through Sool. Everyone wants to lay unambiguous claim to that.

It is imperative that those wishing to support continued political development in Somaliland and throughout the region take full cognisance of looming threats as well as past successes. An appreciation of the historical and cultural context in which recent political development has occurred is equally essential. This, of course, applies just as much to non-Somalis in diplomatic, donor and development communities as it does to diaspora Somalis and those in the Somali Horn.

NOTES

1 Samatar, Said S., “Genius as Madness: King Tewodros of Ethiopia and Sayyid Muhammad of Somalia in Comparative Perspective”, Northeast African Studies 10, No. 3 (2003), p. 29.

2 Walls, M. and Kibble, S., “Somaliland: Change and Continuity”, Report by International Election Observers on the June 2010 presidential elections in Somaliland, Progressio, London, 2011.

3 Kibble, S. and Walls, M., “Swerves on the Road”, Report by International Election Observers on the 2012 local elections in Somaliland, Progressio, London, 2013.

4 Walls, M., A Somali Nation-State: History, Culture and Somaliland’s Political Transition, Ponte Invisibile/ redsea-online.com, Pisa, 2014, p. 178.

5 Lewis, I.M., A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa, James Currey, Oxford, 4th edition, 2002, p.27.

6 Ali, Abdiweli M., “Solidifying the Somali State: Puntland’s Position and Key Priorities”, talk at Chatham House (Royal Institute of International Affairs), London, 24 October 2014.

7 Farah, Mohamed, “A Constitutional Solution to the Political Crisis in Somaliland”, unpublished paper, Academy for Peace and Development, Hargeysa, 2009.