The centenary of the outbreak of the “war to end all wars” in August 1914 will be commemorated throughout Europe. The suffering and loss of life during the conflict will loom large. One signally important theatre of war is likely to remain overlooked – Africa.

The East Africa campaign engulfed 750,000 square miles – an area three times the size of the German Reich – as 150,000 Allied troops sought to defeat a German force whose strength never exceeded 25,000. Its financial cost to the Allies was comparable to that of the Boer War, Britain’s most expensive conflict since the Napoleonic Wars. The official British death toll exceeded 105,000 troops and military carriers. But it was civilian populations throughout East Africa who suffered worst of all in this final phase of the “Scramble for Africa”.

To call the Great War in East Africa a “sideshow” to the war in Europe may be correct, but it is demeaning. The scale and impact of the campaign were gargantuan. The troops, carriers and millions of civilians caught up in the fighting in East Africa should not be forgotten.

Edward Paice is Director of Africa Research Institute and the author of Tip & Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2007).

Mahiwa-Nyangao is certainly not listed among the better-known battles of World War I. Even people living close by these settlements on the B5 road, which runs inland from the southern Tanzanian port of Lindi to Masasi, are unaware of the fighting between British and German colonial troops that raged in their neighbourhood almost a century ago. Yet here, in dense bush, one of the most ferocious actions of the entire East Africa campaign of the Great War took place over four days in October 1917.

Casualties among the 5,000-strong British force – including three battalions from the Nigerian Brigade, three from the King’s African Rifles, and the Bharatpur Infantry and 30th Punjabis from India – were estimated at between one third and a half. The 16 companies of German Schutztruppen opposing them – about 2,000 men – sustained 25% casualties. Equally importantly at this stage of the campaign, when all hopes of resupply from Germany had evaporated, the German units expended nearly a million rounds of precious ammunition during the battle.

The combined casualties at Mahiwa-Nyangao were comparable to those of the bloodiest battle in the Anglo-South African, or “Boer”, War of 1899-1902. In addition to being recognised in contemporary military histories as “one of the greatest battles ever fought in Africa”,1 Mahiwa-Nyangao also prompted the universal acknowledgement that “the courage displayed on both sides by the African soldier, be he Nigerian, King’s African Rifles, or German askari was remarkable”.2

Almost a year after Mahiwa-Nyangao, as the war entered its final phase, German and British forces clashed at Lioma and Pere Hills, to the east of Lake Nyasa in what is today Mozambique. For displays of outstanding courage 28 Distinguished Conduct Medals were awarded to askari of the King’s African Rifles. This was one sixth of the total number awarded to the regiment during the Great War in East Africa – for a single battle. The citations make hair-raising reading. Three British officers were also awarded the Distinguished Service Order. One of them remarked of the askari: “they do not know what fear means; they have won the war for us in East Africa”.3

Although the losses at Mahiwa-Nyangao, the costliest battle of the Great War in East Africa, do not compare with those of the battles at Verdun or the Somme, the campaign was neither minor nor insignificant. The death toll among combatants and civilians was colossal. The privation suffered by the populations of a theatre of war encompassing an area of 750,000 square miles – three times the size of the German Reich – was far worse than in all but a handful of areas of Europe traversed repeatedly by fighting. The financial cost to the Allies was comparable to that of the Anglo-South African War.

1st King’s African Rifles occupying Longido in German East Africa early in 1916

The first shot fired by a British unit anywhere in the Great War was from the rifle of an African soldier – Regimental Sergeant-Major Alhaji Grunshi of the Gold Coast Regiment – as an Anglo-French force invaded the German colony of Togoland (today’s Togo) on 7 August 1914. The last German troops to surrender did so in Northern Rhodesia (today’s Zambia) on 25 November 1918, fully two weeks after the Armistice in Europe.

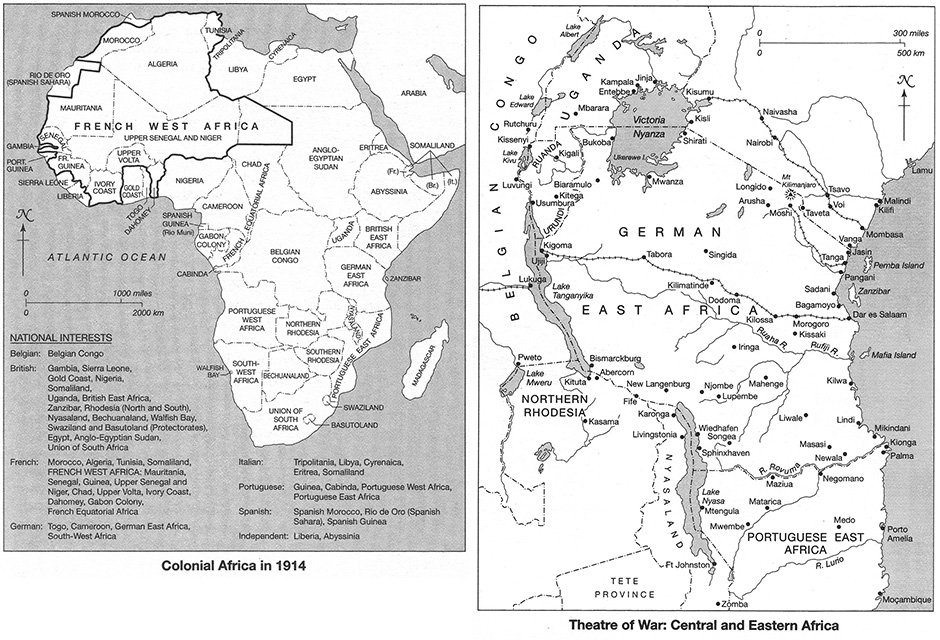

Togoland fell to an Anglo-French force after a fortnight, German South-West Africa was taken by South African troops in mid-1915 and German resistance to British, French and Belgian colonial troops in Cameroon finally ended in March 1916. But the Allies’ attempt to overcome German East Africa from the six neighbouring British, Belgian and Portuguese colonies – and German resistance – was of an altogether different magnitude.

About 150,000 Allied combatant troops were deployed against an enemy whose strength never exceeded 25,000

At the outbreak of war in Europe the prospect of small colonial defence forces of a few thousand African troops in each colony waging war against each other was as remote as the likelihood of the “main show” lasting beyond Christmas 1914. But over the next four years more than 125,000 British imperial and South African troops served in the East Africa campaign, Portugal sent 20,000 men in a number of expeditionary forces to Portuguese East Africa (today’s Mozambique) and Belgium threw 15,000 men of the Congolese Force Publique into the fray.

In all, about 150,000 Allied combatant troops were deployed against an enemy whose strength never exceeded 25,000. The total ration strength of British imperial forces – combatant and non-combatant – in the final phase of the war was still over 110,000 men, despite the fact that the headcount of the enemy they were by then pursuing through Portuguese East Africa, back into German East Africa and then into Northern Rhodesia had dwindled to a few thousand.

Improbable as it seemed to civilians and colonial authorities alike in Africa in August 1914, an imperial war on the continent – a final, bloody phase of the “Scramble for Africa” – had been considered a very real possibility by European leaders from the mid-1890s. In May 1896, Joseph Chamberlain, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, warned the House of Commons that such a conflict would be “one of the most serious wars that could possibly be waged…It would be a long war, a bitter war and a costly war…It would leave behind it the embers of a strife which I believe generations would hardly be long enough to extinguish.”

Three years after Chamberlain’s warning war did break out in Africa. Although it pitted Britain against the Boer republics of South Africa rather than a rival European power it was unmistakably imperialist in character and intent. Far from being the rapid and immediately profitable pushover envisaged by British hawks, the Anglo-South African war lasted two and a half years, involved the mobilisation of more than 400,000 British and colonial troops and left much of South Africa in ruins.

“In money and lives”, wrote the historian Thomas Pakenham, comparing the cost of the conflict to the Napoleonic Wars, “no British war since 1815 had been so prodigal.”4 The bill to the British Treasury was over £200m, £12bn in today’s money and ten times the value of the coveted output of the Transvaal gold mines in 1899. British casualties exceeded even those of the Crimean War half a century earlier; and the toll wrought on Afrikaner and African alike was immense.

None of Britain’s European rivals intervened in South Africa. But Germany, France and Russia roundly criticised the aggression, and incidents elsewhere in Africa exacerbated imperial tensions. In 1898, war between Britain and France over an incursion by the latter into the upper reaches of the Nile was only averted by the narrowest of margins. Belgium and Portugal were intensely suspicious – with good reason – that Britain, France and Germany meant to dispossess them of their vast African empires.

Many prominent and well-informed individuals even

believed that Africa was a prime cause of the whole conflict

Despite a period of Anglo-German entente in Africa immediately before the outbreak of war and a widespread belief in Africa that the palaver in Europe would not touch the continent, by the end of August 1914 the British government was planning military action against German ports and wireless stations in Africa and the creation of Mittelafrika, a “second Fatherland” straddling all of central Africa, had become a fundamental war aim of the German government.

The backdrop of three decades of imperial rivalry in Africa is crucial to understanding how the Great War came to be fought there as well as in Europe. Many prominent and well-informed individuals even believed that Africa was a prime cause of the whole conflict. At the Pan-African Conference in 1919, William DuBois, the African-American activist and founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, declared that “in a very real sense Africa is a prime cause of this terrible overturning of civilization which we have lived to see [because] in the Dark Continent are hidden the roots not simply of war today but of the menace of wars tomorrow”.5 In similar vein, Sir Harry Johnston, the African explorer and administrator, was convinced that “the Great War was more occasioned by conflicting colonial ambitions in Africa than by German and Austrian schemes in the Balkans and Asia Minor”.6

Although the importance of Africa to imperial rivals meant that the war may have shared the same roots as the conflict in Europe, the conduct of the campaign in East Africa could not have been more different. For the most part it was as mobile as trench warfare was static, but equally attritional.

When 50,000 British, Indian, South African and Belgian troops advanced into German East Africa from the north and east in early 1916 they did so on a front 1,500 miles long – nearly three times the distance from Calais to Nice. In 1918, when the fighting had moved to Portuguese East Africa, the area of operations for just 12,000 British and German combatants was two-thirds the size of France. That year a column of two King’s African Rifles battalions marched 1,600 miles in seven months, forded 29 large rivers and fought 32 engagements. In July alone it covered 330 miles virtually without rations, subsisting on what could be foraged. When the officers and men were inspected at the end of their stint in the field they were described as resembling the victims of famine. Their experience of the hardships of war in East Africa was typical, not exceptional.

In the north-west Belgian troops commanded by Colonel Tombeur advance towards Tabora, capturing the town in September 1916

The war in East Africa, in the words of the quartermaster of the Cape Corps, a unit raised from South Africa’s “coloured” population, “involved having to fight nature in a mood that very few have experienced and will scarcely believe”.7 The accounts of many a British – and German – combatant in East Africa attest to the fact that “there is no form of warfare that requires so much inherent pluck in the individual as bush fighting”; and to the terrible loneliness which “tested the nerves of the bravest”.8 In 1917 an officer in the 40th Pathans who had fought on the Western Front wrote: “what wouldn’t one give for the food alone in France, for the clothing and equipment. For the climate, wet or fine”.9

Disease was a bigger killer of British troops than combat, exacerbated by the poor supply of inadequate rations and a scandalously deficient medical establishment. The troop return of the Gold Coast Regiment is instructive. By the time it returned to West Africa at the end of its service the regiment had sustained 50% casualties in a force 3,800-strong. Those killed in action numbered 215 whereas 270 had died from disease. The wounded totalled 725, those invalided by disease 567.

Keeping troops supplied with adequate food and within reach of rudimentary medical attention was virtually impossible. The supply line for General Northey’s troops in Northern Rhodesia extended back to Durban, via Portuguese East Africa – the longest supply line of any British force in the Great War. As the availability of livestock for transport proved incapable by mid-1916 of matching the depredations of disease, the onus fell on the only alternative – human porterage. The mathematics are sobering. For example, the distance from the railhead to Northey’s front was 450 miles. This meant that 16,500 carriers were required to transport a single ton of supplies – enough to feed 1,000 askari and their camp-followers for one day – for the simple reason that 14,000 of them were needed to carry food for the column while 2,500 carried the food for the troops.

In the first two years of the war service as a military carrier was voluntary, short-term and remunerated nearly as well as service as an askari in the King’s African Rifles. But as the theatre of war and number of troops expanded, carriers’ pay was cut to a pittance and recruitment became in effect by force. The seeds of one of the greatest tragedies of the Great War were sown.

*“It’s a long way to Tipperary”: King’s African Rifles marching song

The official death toll among British imperial troops who fought in East Africa was 11,189 – a mortality rate of 9%. Total casualties, including the wounded and missing, were a little over 22,000. But the troops required more than a million carriers to keep them in the field. No fewer than 95,000 carriers died, bringing the total official death toll of the British war effort to more than 105,000. Among African soldiers and military carriers recruited from British East Africa alone, today’s Kenya, more than 45,000 men lost their lives. This equated to about one in eight of the country’s total adult male population.

The true figures were undoubtedly much higher. As many a British official admitted, “the full tale of mortality among native carriers will never be told”.10 Even 105,000 deaths is a sobering figure. It equals the number of British soldiers killed in the carnage on the Somme between July and November 1916. It is more than 50% higher than the number of Australian or Canadian or Indian troops who gave their lives in the Great War – and whose sacrifice is much more widely recognised. Indeed the death toll alone in East Africa is comparable to the combined casualties – the dead and wounded – sustained by Indian troops in the Great War.

The troops required more than a million carriers to keep them in the field

The scale of the catastrophe which befell the men employed or impressed as carriers did not attract immediate attention in Europe or Africa, not least because the compilation of statistics was delayed by the many problems of demobilisation. Even when the details began to emerge in the summer of 1919 the Chief of the Colonial Division of the American delegation at the Paris Peace Conference speculated that “the number of native victims…may be too long to give to the world and Africa”.11

There were many British combatants in East Africa who paid tribute to the carriers on whom they were utterly dependent for survival. General Northey declared that he “would award the palm of merit to the [carriers]”.12 Colonial officials warned the military establishment in 1917 of the consequences of seeking to mobilise virtually every adult male in the entire theatre of war. But when the mortality rate became common knowledge in Whitehall it was deemed a “bloody tale” best ignored, or even suppressed, as Britain sought colonial prizes in Africa at the Paris Peace Conference. As one colonial official put it, in particularly arresting terms: the conduct of the campaign “only stopped short of a scandal because the people who suffered the most were the carriers – and after all, who cares about native carriers?”13

The logistical challenges – and the solution – were no different for German commanders. No fewer than 350,000 men, women and children undertook carrier “duty” and it is inconceivable that the death rate among them was lower than one in seven. In contrast to the practice in British colonies, no records were kept for the carriers and, with the exception of those permanently attached to German units, they were not paid.

To exclude dead carriers from the death toll of the Great War in East Africa, as has been the case for a century, is unacceptable. At best it fails to recognise that the campaign could not have been fought without them; at worst, it is tantamount to depicting them as somehow not human.

As for the financial cost, when the contributions of India, South Africa and Britain’s African colonies were included the bill, in the words of one senior colonial official, “approached, if it did not actually exceed that of the Boer War”.14

The brunt borne by East Africans during the conflict was not limited to carrier service. In German East Africa newly harvested crops were routinely requisitioned by German colonial troops without payment. In 1916, in central Ugogo district, the effects were exacerbated by poor rainfall and the following year brought a famine during which one fifth of the population died. All told, an estimated 300,000 civilians perished in German East Africa, Ruanda and Urundi as a direct consequence of the authorities’ conduct of the war, excluding those conscripted for carrier service. This was an even higher death toll than that inflicted by German colonial troops during the suppression of the Maji-Maji rebellion a decade earlier.

Although the peacetime administration was less dislocated in the British colonies and protectorates, sowing and harvesting were disrupted almost everywhere – by the weather if not by the absence of men on carrier service or fighting. Food price inflation, tax rises and increasingly repressive land and labour laws compounded the hardships. “People in South Africa tell me they are sick of hearing about the German East Africa campaign; I’m sure that these poor natives in East Africa are pretty sick of it too”,15 wrote an officer in the 5th South African Infantry in late 1917.

The worst calamity of all was saved for last. For the surviving troops and carriers on both sides, and for the civilian populations prostrated by four years of fighting, October 1918 – “Black October” – brought something worse than total war. The Spanish influenza epidemic spread far more rapidly along the wartime lines of supply and communication than it would otherwise have done. This new curse was so virulent that a man could simply drop dead while on a short walk.

The official influenza death toll for British East Africa was 160,000. But it is unlikely that fewer than 200,000 died – a far greater loss of life than that caused by the war itself and nearly a tenth of the total population of the country. By the time the epidemic was over 1.5-2 million had died in sub-Saharan Africa in a matter of months. It was the final, diabolical confirmation that the Great War in East Africa was above all a war against nature and a humanitarian disaster without parallel in the colonial era. One phrase was common to many oral histories of the time: “there came a darkness”.

A post-war booklet declared that “if there had been no war in Europe the campaigns in the German colonies [in Africa] would have compelled the interest of the whole world”.16 The point is a good one. Using any yardstick but the war in Europe, the scale and scope of the Great War in East Africa, in particular, was gargantuan. It produced cameos of extraordinary courage and preposterous improvisation on land, on sea and in the air to rival anything witnessed in the “main shows”. Comparison with the Anglo-South African War is arguably more appropriate than comparison with the “main show” of the Great War, the Western Front.

The fighting in East Africa – and its consequences – also put the highfalutin’ talk of the European powers of their so-called “civilising mission” in Africa, and imperialism itself, on trial. In so doing it exposed unremitting colonial ambitions to adegree of scrutiny unsurpassed since the beginning of the Scramble for Africa. As William DuBois lamented at the Pan-African Conference, “twenty centuries after Christ, black Africa, prostrate, raped and shamed, lies at the feet of the conquering Philistines of Europe”.

If there had been no war in Europe the campaigns in the German colonies [in Africa] would have compelled the interest of the whole world

In East Africa, the memorials and graveyards of the fallen attract little attention. Elsewhere Africa’s involvement in the Great War is all but forgotten. There is no askari or carrier monument in London. The best-known accounts of the war are fictional – C.S. Forester’s The African Queen, Wilbur Smith’s Shout at the Devil and William Boyd’s Booker Prize-nominated An Ice Cream War. If an episode is recalled at the mention of the conflict, it is usually of the thrilling adventure variety: Germany’s attempt to resupply the troops in East Africa by Zeppelin in 1917; the extraordinary British naval expedition to capture Lake Tanganyika; the thrills of the British operation to sink the German cruiser Königsberg in the Rufiji Delta in 1915; the determination and ingenious guerrilla tactics of the German commander, von Lettow-Vorbeck. Perhaps the disastrous British expeditionary force landing at Tanga in the first months of the war, a precursor of the disaster at the Dardanelles in 1915, might be vaguely familiar.

These episodes have their place. But they are corners of a much larger canvas. They should not be allowed to obfuscatethe reality of war to the detriment of the memory of those who fought and the suffering of the civilian population. The voices and memorials of the Great War in East Africa are predominantly European. But African combatants and carriers called upon to march twenty miles a day for months on end, in searing heat and torrential rain, subsisting on minimal rations and out of reach of medical resources, would have concurred with the sentiment expressed by one young British officer. In 1914 Lt Lewis had witnessed the slaughter of every single man in his half-battalion on the Western Front and had experienced the horrors of trench warfare. Sixteen months later, in a letter to his mother from the East African front, Lewis wrote: “I would rather be in France than here”.17

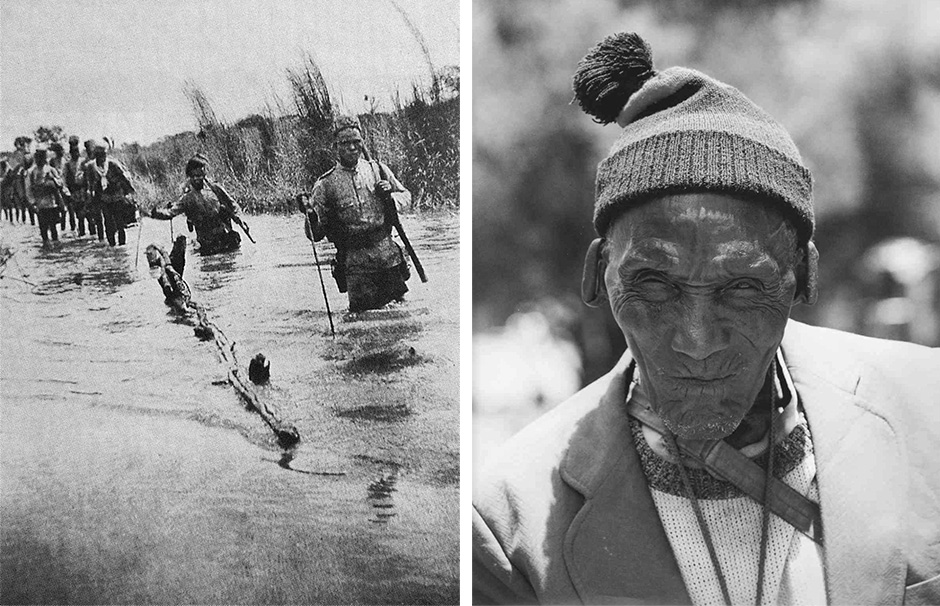

Left: Askari of 2/4 King’s African Rifles in Portuguese East Africa.

Right: M’Ithiria Mukaria, the oldest surviving veteran of the King’s African Rifles, in Isiolo (photographed by the author, February 2002)

NOTES

1 Downes, W.D., With the Nigerians in German East Africa (Methuen, 1919), p.226

2 Haywood, A., and Clarke, F., The History of the Royal West African Frontier Force (Gale & Polden, 1964), p.235

3 Matson papers 5/14, p.159, Bodleian Library of Commonwealth and African Studies at Rhodes House

4 Pakenham, T., The Boer War (Abacus, 1992), p.572

5 DuBois, W.E.B., The African Roots of War, Mary Dunlop Maclean Memorial Fund Publication No.3 (1915), p.714

6 African World Annual, 1919, p.29

7 Difford, I., The Story of the First Battalion Cape Corps (privately published, Cape Town, 1920), p.93

8 Sheppard, S.H., “Some Notes on Tactics in the East African Campaign”, Journal of the Royal United Services Institution, February 1942, pp. 138-9

9 Thornton papers, Imperial War Museum

10 Duff, H., “White Men’s Wars in Black Men’s Countries”, National Review, Vol. 84 (1925), p.909

11 See Steer, G.L., Judgement on German Africa (Hodder & Stoughton, 1939), p.262

12 Northey papers, Imperial War Museum

13 CO/820/17, The National Archives

14 Duff, op. cit.

15 Lt Rice in The Nongqai, November 1918, p.508

16 See Foreword, Through Swamp and Forest: The British Campaigns in Africa, (privately printed, undated)

17 Lewis papers, letter dated 15 April 1916, Imperial War Museum