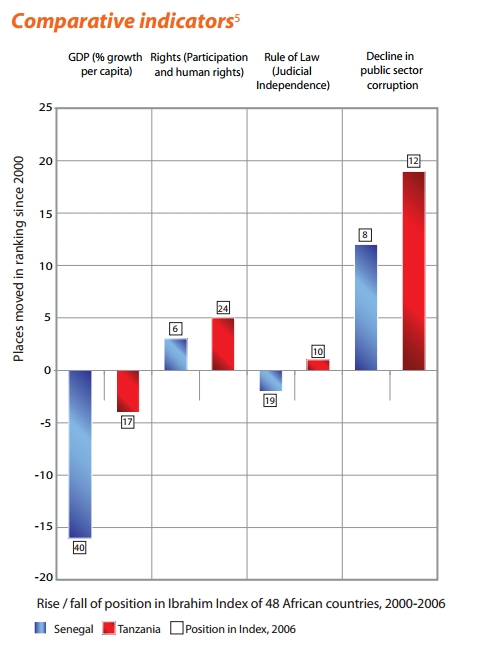

Tanzania and Senegal have long records of political stability. Both made peaceful transitions from single-party ‘African socialism’ to multiparty democracy, becoming favourites with foreign donors and development agencies.

Recent elections were declared free and fair by international observers, but the course of institutional reforms in each country has diverged. These notes compare the prospects for democratic institutions.

State of the nations Peace and stability in Tanzania and Senegal have attracted financial rewards. Tanzania receives more development aid per capita from the G8 group of industrialised nations than any other African country. Senegal, a secular Muslim democracy, retains generous bilateral support from the US. In September 2009, the American government’s Millennium Challenge Corporation announced a financial assistance package for Senegal worth US$540 million over five years. Each country

receives more donor funding per capita from Britain and France, respectively, than any of their other former colonies.

Neither country possesses oil or mineral reserves of strategic significance. Senegal has never experienced a coup, and there has been no serious internal strife in Tanzania since 1964. Despite religious and ethnic diversity, an enduring peace has withstood separatist movements in the southern Casamançe region of Senegal and on Zanzibar.

Tanzania’s legislative elections in 2005 were won by Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), the ‘Party of the Revolution’ which has dominated Tanzanian politics since independence. But President Jakaya Kikwete’s campaign promises for more open and accountable government encouraged advocates of greater autonomy for Tanzania’s democratic institutions.

Also Read: Diehards and democracy: Elites, inequality and institutions in African elections

In Senegal, the main opposition parties boycotted legislative elections in June 2007 amid accusations of irregularities in the presidential election earlier in the year. The boycott consigned parliamentary opposition to just half a dozen MPs. The overwhelming majority of the Sopi, or Change, coalition has enabled it to centralise power at the expense of political institutions.

Because of this president’s leadership and that of his two esteemed predecessors, if you want to see a country that is on the road to progress, go to Senegal. – Hillary Clinton, US Secretary of State (1)

The Tanzanian parliament has brought in legislation to empower key institutions, while its counterpart in Senegal has overseen a weakening of supervisory bodies. Yet Senegalese voters have been able to elect an opposition party to power. While Tanzania’s reforms have been sanctioned by a party that has been in power since independence, they have not secured the unanimous support of CCM’s members.

Tanzania

Political inheritance

At independence, Senegal and Tanzania’s first leaders argued that political stability would be threatened by multiparty democracy. Julius Nyerere – Tanzania’s Mwalimu, or Teacher – established a single party state embracing ‘African socialism’. By the early 1980s Nyerere’s policy of villagisation and collective farming, Ujamaa or Familyhood, had failed.

Tanzania became heavily dependent on foreign donors who urged multiparty democracy. Nyerere stepped down voluntarily in 1985 and his successor, Ali Hassan Mwinyi, oversaw the transition to a plural system. Tanzania’s political framework is a hybrid of presidential and British parliamentary models. Executive power is vested in the president, but the daily business of government is conducted by ministers who, following the Westminster system, retain their parliamentary seats.

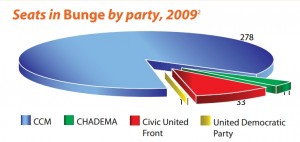

Since the introduction of multiparty polls in 1992, Tanzanian opposition parties have won fewer seats in each successive election. None has secured more than 15% the number of seats in Bunge gained by CCM. In 2005, the two largest opposition parties, Civic United Front and Chama Cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo(CHADEMA), secured 22.5% of the vote but only 42 of 323 seats. Independent candidates are not permitted to stand for election.

The election of Samuel Sitta as Speaker ofBunge in 2005 by an overwhelming majority of MPs reflected an appetite for reform among parliamentarians. Sitta, a former minister for justice and constitutional affairs, has led a drive to improve the ‘oversight’ and ‘challenge’ functions of Bunge. According to Sitta: “The ideal situation is to have the teeth and also to have the meat to chew on.” (3) Two high-profile corruption investigations were concluded without interference.

BoT and Richmond

In early 2008, opposition MPs played a leading role in bringing allegations of corruption at the Bank of Tanzania to the attention of Bunge – a story covered extensively by the independent media. The exposure of fraudulent payments worth US$120 million to 22 local firms led to the sacking of the bank’s governor, Daudi Ballali. Thirteen people were arrested and charged by state prosecutors with fraud, conspiracy and theft in November 2008. Hearings began in June 2009.

Bunge, and CCM MPs, were responsible for uncovering the Richmond Development Company scandal in 2007. Concerns raised by William Shelukindo, chairman of the Trade and Investment Committee, prompted Samuel Sitta to appoint a select committee to investigate a contract for emergency electrical generating capacity awarded to Richmond. Led by lawyer and CCM MP Harrison Mwakyembe, the committee reported its findings within a month of the exposure of the Bank of Tanzania scandal. Prime Minister Edward Lowassa and two other ministers implicated in the findings resigned and cabinet was dissolved.

Democratic Dodoma

The appointment of the Richmond select committee was made possible by a revision of the Standing Orders which regulate the working of Bunge. Reforms adopted in 2007 encourage greater parliamentary debate and enhance the supervisory role of parliamentary committees. Previously, any request from MPs for a committee of enquiry was readily quashed by the ruling party. In 2006 no request for any kind of investigation was proposed in parliament.

Other reforms incorporated in the new Standing Orders give MPs a larger role in law-making, and require the prime minister to appear regularly in Bunge for Prime Minister’s Questions. The creation of a new National Assembly Fund has assigned control of the parliamentary budget to a Commission of Parliament chaired by the Speaker. A new Corporate Action Plan for parliament will set priorities for Bunge, backed by a ‘Democratisation Fund’ to which the World Bank contributed US$19m in 2008.

The National Assembly Fund is a sign that the government has accepted that parliament should be completely independent. – Samuel Sitta, Speaker of Bunge (4)

Under the new Standing Orders, the report of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) must be debated by Bunge. The PAC reports to Bungewith an analysis of the annual report of the Controller and Auditor General (CAG), followed by a two-day debate in parliament. Previously, no such discussion was required. The CAG is empowered to take legal action against suspected public sector fraudsters.

Also Read: Old Tricks, Young Guns: Elections and violence in Sierra Leone

Three new committees – the Local Authorities Accounts Committee, the Public Investments Committee, and the Public Organisations Accounts Committee – have been set up to increase parliamentary oversight of state spending. In the Westminster tradition, all three accounting bodies are headed by members of the opposition. A new Public Audit Act, processed under a presidential certificate of urgency in July 2008, established the financial and managerial autonomy of the National Audit Office under Auditor General Ludovick Utouh.

Senegal

Democratic Dakar

Léopold Senghor, Senegal’s poet president and founder of the Négritude movement, adopted a less radical version of African socialism at independence than Tanzania’s Nyerere. But economic dependence on groundnut exports, compounded by falling prices and drought, proved as damaging as Ujamaa. Senegal also became reliant on foreign aid, while donors pressed for democratic reform. In 1981, Senghor became the first African president to step down voluntarily. His protégé, prime minister Abdou Diouf, oversaw the transition to multiparty elections.

As the administrative and commercial centre of l’Afrique occidentale française, the collective term for France’s eight West African colonies, Senegal inherited a framework of political institutions from its former colonial power. Effectively, power rests with the president – as in Tanzania. But ministers can be selected from outside the ranks of elected officials. Those appointed from within parliament must surrender their seats to a suppléant, or replacement. French remains the official language for government business, although fewer than one in four Senegalese speak it fluently.

In 2000, Abdou Diouf lost the presidential election and relinquished power without protest to Abdoulaye Wade, after four terms as president. The reform of electoral institutions, begun in the late 1970s, culminated in the defeat of the Parti Socialiste, the governing party since independence – a political landmark dubbed ‘the coming of age of democracy’ in Senegal. The election was regarded as one of the most free and fair to have taken place in Africa.

Senegal’s democratic credentials were called into doubt in 2007. The main opposition parties boycotted legislative elections in the hope of forcing their cancellation and prompting an enquiry into the conduct of the presidential elections earlier that year. The gamble proved to be a miscalculation. Wade’s Sopi coalition took 131 of 150 seats in the National Assembly.

A malleable constitution

A new constitution was introduced by Wade’s government in 2001 to fulfil promises for reform made during his presidential campaign, but it has undergone regular revision. Wade and his coalition have amended the constitution 11 times since the beginning of 2007. Amendments have eroded the independence of parliament and increased presidential powers. The constitution remains vulnerable to political interference because most articles can be amended by a three-fifths majority vote in parliament.

The Senate, the second chamber of parliament, was abolished in 2001 – discredited for its record as a means of distributing patronage under the Parti Socialiste. In 2007, it was reinstated. Of 100 seats, 65 are directly appointed by the president. In its former incarnation, only one fifth of the members were presidential appointees.

In 2008, the term of the President of the National Assembly – equivalent to Bunge’s speaker – was reduced from five years to one by constitutional amendment. Incumbent Macky Sall, a former prime minster and campaign director for Abdoulaye Wade, was subsequently sacked. Sall had summoned Wade’s son, Karim, in his capacity as President of the National Agency of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (l’Anoci), to answer questions about construction sites for the 2008 OIC summit.

Budgetary oversight

The Cour des Comptes, the administrative court of specialised magistrates charged with preparing the annual report on public accounts for parliament, has not received details of government expenditure for 2007 and 2008.6 The loi du règlement, a law which should be passed annually, confirming parliament’s approval of public accounts, has not been passed since 1999. Some newer MPs remain unaware of the requirement to pass such a law.

An attempt by the Cour des Comptesto expand its mandate and resources appeared to have gained presidential support, but in 2008 the proposed legislation was withdrawn by the government following an inspection of Karim Wade’s l’Anoci (7). Meanwhile l’Inspection Générale de l’État, a body which answers directly to the president and was charged with monitoring public accounts prior to the creation of the Cour des Comptes in 1999, continues to work in parallel.

Presidents, parties…

In the absence of any split in CCM ranks, the governing party will retain power in Tanzania for the foreseeable future. Approval ratings for President Kikwete have dropped by almost a fifth since 2005, but he remains six times more popular than his closest rival, CHADEMA’s Freeman Mbowe (8). Civic United Front and CHADEMA, the main opposition parties, will remain minority players.

In contrast, Senegal’s multiparty system is firmly entrenched. Abdoulaye Wade’s victory in the 2000 presidential election demonstrated that voters could bring an opposition to power. In the 2009 local elections, the electorate once again backed an opposition coalition. Benno Siggil Senegaal, Wolof for ‘united to boost Senegal’, won in all but one of the cities. Against a backdrop of rising food prices and unemployment, the ballot was regarded as a test of popular support for Sopi’s performance ahead of presidential and legislative polls in 2012.

Speculation that President Wade is grooming his son Karim as his successor has provoked dissent in Senegal, but few voters fear an illegal transfer of power. On his first foray into politics in 2009, Karim Wade, who speaks French as a first language and is not fluent in Wolof, failed to win Dakar’s mayoral contest. He was subsequently appointed to his father’s cabinet as minister of state for international cooperation, urban and regional planning, air transport, and infrastructure.

…and institutions

Reforms in Tanzania have raised hopes of greater transparency in the allocation of national resources and donor funds. Procedural and legal changes reduced institutional dependence on the executive. The new Standing Orders and Public Audit Act increased the autonomy of key oversight bodies. Their work, notably in exposing corruption, has been widely reported in Tanzania’s vibrant press.

Institutional reform in Tanzania will depend on continued support from CCM parliamentarians. MPs who advocate further reforms believe they have the tacit support of President Kikwete, or at least that he will not impede them. Samuel Sitta, Bunge’s reforming Speaker, remains unhappy about the influence of party whips in limiting debate: “In the early years of the one-party state we used to have a much freer atmosphere in terms of discussions in parliament, because party loyalty was not an issue.” (9) He would welcome a legal challenge to test party rules against Article 100 of the constitution which guarantees free speech in parliament.

Also Read: After Borama: Consensus, representation and parliament in Somaliland

The conduct of some CCM MPs in recent days shows that there is neither protocol nor discipline. MPs sometimes openly confront ministers. The NEC will not hesitate to expel such members from the party and remove them from their leadership posts. – John Chiligati, CCM ideology and publicity secretary (10)

The reform agenda has threatened the hegemony of the party elite, causing ructions within CCM. In August 2009, the issue of party discipline was prominent in a ‘dialogue’ between Samuel Sitta and CCM’s National Executive Committee. A three-man team led by former president Ali Hassan Mwinyi was appointed by the committee to ‘monitor’ and ‘moderate the conduct’ of MPs. In the ensuing media ferment, opposition leaders and CCM colleagues voiced concern that the party was attempting to gag parliament.

Senegal’s institutions have proved unequal to the will of an executive with a overwhelming parliamentary majority. The governing party has modified to its own advantage the constitution it introduced in 2001. The electoral code has been altered repeatedly, the Senate has been re-established, and the term of the Speaker has been radically reduced. Other institutions have been similarly adapted, abolished or reinstated, according to the priorities of the executive (11).

The case for a more resilient constitution features prominently among recommendations drawn up by the committee of the Assises Nationales, a public consultation organised by opposition and civil society groups. Its report proposes that constitutional amendments which influence the role of state institutions should be put to national referendum.

A win for Sopi in the 2012 legislative elections is unlikely to reverse the trend of weakening institutions. The dismissal of former Speaker Macky Sall and reduction of the Speaker’s term to one year discourage would-be reformers. The expulsion of two Sopi MPs, perceived to be allies of Sall, demonstrates that dissent will not be tolerated in the governing coalition. L’alternance, the democratic transfer of power, is a source of pride in Senegal. But to nurture democratic institutions will require determination and support from parliament, a task which has proved harder than the election of a new government.