February 2016

On 29 January 1986 Yoweri Kaguta Museveni addressed Ugandans for the first time as national leader: “No one should think that what is happening today is a mere change of guard; it is a fundamental change in the politics of our country”. Given that Uganda had been led by seven presidents and a presidential commission in the preceding seven years, few could have expected that Museveni would remain at the helm 30 years later.

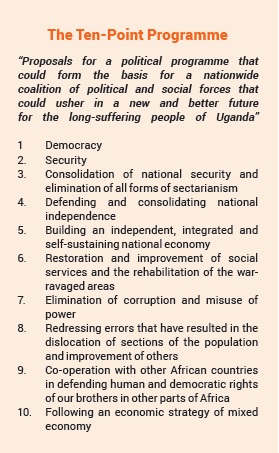

The National Resistance Army and its political wing, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), took power after a bush war that began in 1980. The NRM’s ten-point programme, debated and agreed during 1984, sought to “usher in a new and better future for the long-suffering people of Uganda on the back of a grassroots campaign to seize power”. It promised a peaceful, democratic future, free from corruption, and with basic services and economic opportunity for all citizens.

Thirty years on, it has become increasingly difficult to differentiate between the Ugandan state, its dominant political party (the NRM) and its leader (Museveni). On 18 February, Ugandans will vote in presidential and legislative elections. This Briefing Note considers the extent to which the promises of the ten-point programme have been fulfilled.

Power to the people

In 1986 the NRM promised “popular democracy” and began to dismantle Uganda’s political structure. In 1992, political parties were banned, giving rise to a no-party or “movement” system. Museveni said this would provide a platform for more inclusive politics and encourage Ugandans to move beyond divisive tribal rivalries prevalent during the previous three decades.

Devolution of power was a key tenet of NRM policy. Deployed as a strategy for popular engagement during the bush war, in the late 1980s a five-tier system of elected government was rolled out in villages, parishes, sub-counties, counties and districts nationwide. The 1993 Local Government Statute was arguably the most promising reform initiated during the NRM’s early years in power. However, no village or parish elections have taken place since 2001.

Turnout for presidential polls, which have returned the same winner four times in a row, fell from 72.6% in 1996 to 59.3% in 2011

A lack of proportionate resources has hampered devolution. By 2013, district authorities were expected to deliver 80% of government services – including primary education, healthcare and urban planning – with just 17% of the national budget. The government acknowledges that more than 30% would be required for local government to operate as envisaged.1 Despite its early promise, local administration has become more of a political project than a service provider. Since 1986, the number of districts has grown from 30 to 112. The increase in the number of political office holders has not meant more representative governance.

Uganda’s constitution-making process, commenced in 1989, was, at the time, unsurpassed in Africa in terms of civic participation: 25,547 separate submissions were received from citizens, institutions and local councils But by the time the constitution was adopted in 1995, the process “had been manipulated by the NRM to entrench it and its leaders hold on power”. While political and civil rights were provided for and legislative oversight extended, the presidency was invested with “significant powers of appointment”.2 Subsequent amendments impinged on the constitutional rights of citizens and parliament, notably the removal of presidential term limits in 2005. To appease critics, less than a month later the government reintroduced a multi-party system.

The (NRM) political machine

Uganda now has many political parties, holds presidential and parliamentary elections every five years, and has a vibrant and critical press. The ninth parliament comprises 386 members, of whom more than one-third are women. The armed forces, youth and the disabled are represented. Vigorous debate is a noted feature of the assembly.

Despite media coverage of huge election rallies and competitive campaigning, electoral participation has dwindled. Turnout for presidential polls, which have returned the same winner four times in a row, fell from 72.6% in 1996 to 59.3% in 2011. Citizens are increasingly convinced that an NRM victory is the only outcome and vote accordingly. The long term legacy of movement-dominated politics, combined with control of state resources and restrictive legislation such as the Public Order Management Act 2013, which outlaws political gatherings of three or more people without prior permission from the police, has stymied genuine opposition to the NRM.

The NRM relies on a strong rural support base to deliver electoral victory. A powerful executive controls the influence of parliament on the legislative agenda and oversight of government expenditure. Internal party divisions have become more noticeable. In 2013, amid “allegations of misbehaviour and insubordination”, the party expelled four MPs who were trying to expose corrupt government officials. However, “young turks” have yet to pose a significant challenge to Museveni’s grip on power.

Peace at last?

In his 2014 independence day address, the president remarked that all Uganda was finally at peace for the first time in 114 years. While the narrative of the NRM as guarantor of peace is grounded in fact, it underplays the persistence of domestic conflict. Military action against the Lord’s Resistance Army affected northern districts for almost two decades, displacing as many as 1.5 million people. Why it took the well-equipped Ugandan People’s Defence Force so long to bring a couple of thousand rebels to heel confounded many. By the time it did so, many northerners could not regard the troops as liberators. The lack of a government or International Criminal Court investigation into alleged abuses on both sides has created a legacy of “negative peace”.3

To some extent, Museveni and the NRM benefited from the protracted conflict. Instability in the north prevented opponents from establishing a power base in the region, were a pretext to curb freedom of expression, and attracted US funding and assistance with training for the security forces. Museveni progressively – and shrewdly – positioned Uganda as a guarantor of regional stability and key ally of the West in the war on terror. The country borders the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and South Sudan, and has maintained sizeable peacekeeping forces in Somalia. Museveni has consistently turned regional geo-politics to his advantage. In addition to attracting substantial funding, this has deflected censure from donors over issues such as governance and corruption.

Security forces are often deployed against other, non-military threats. They regularly intimidate “dissidents” and opposition figures, with Dr Kizza Besigye a particular target during election campaigns. Museveni’s former physician and long-time political rival, Besigye has frequently been subjected to court indictment, house arrest and physical violence. In 2011, during the “Walk to Work” demonstrations that followed post-election price rises, police tear-gassed and shot at protesters with live ammunition, killing nine people. In riots in Buganda in 2009, security forces killed 20 people and injured more than 50. Stephen Oola, head of research and advocacy at Refugee Law Project, believes “the militarisation of the police is the single biggest insecurity factor in Uganda”.4

Uganda has consistently been one of the fastest growing African economies

Crime prevention has been less than successful, with no improvement in statistics since 2009. Ahead of the 2016 elections, Inspector General of Police Kale Kayihura, a key Museveni ally, began the mass recruitment and training of 1.6 million “crime preventers”, 30 for each village nationwide. Recruits are mostly young, unemployed men, who are enticed by the prospect of paid work in the future. Officially, their role is to provide volunteer security services. More often, they intimidate and repress opposition supporters. In 1986 the NRM promised to abolish state-sponsored violence; in 2011 the Uganda Law Society said that the country was increasingly “akin to a police state”.5

Sowing the mustard seed 6

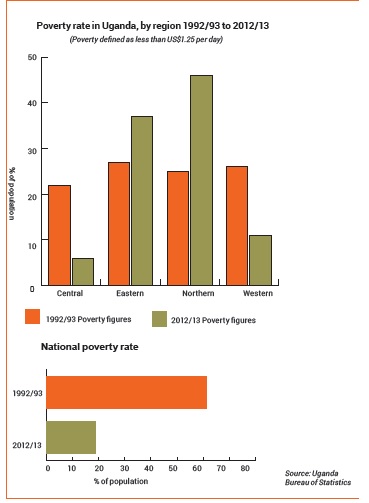

The ten-point programme described economic development as “probably the most important part”. Uganda has consistently been one of the fastest-growing African economies. Real gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 7% a year in the 1990s and 2000s. Sustained growth was a key factor in reducing the number of Ugandans living below the poverty line from 9.8 million in 1992/3 to 6.7 million in 2012/13.

The ten-point programme described economic development as “probably the most important part”. Uganda has consistently been one of the fastest-growing African economies. Real gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 7% a year in the 1990s and 2000s. Sustained growth was a key factor in reducing the number of Ugandans living below the poverty line from 9.8 million in 1992/3 to 6.7 million in 2012/13.

The country’s status as a “donor darling” has underwritten economic growth. In 2013, it received US$1.8bn in official development assistance (ODA), of which the US and the World Bank contributed almost 40%. According to the OECD, ODA accounted for 42% of the government budget in 2006; in 2012/13, it was equivalent to about 25%. After 30 years, the NRM’s stated goal of achieving “self-sustaining economy” remains elusive.

The adoption of externally sponsored structural adjustment programmes during the 1990s made the NRM’s initial plan to promote domestic manufacturing and industrialise agriculture impracticable. Momentum was never regained even after debt relief, which peaked at US$5.9bn in 2006. Up to 80% of Ugandans still depend on subsistence agriculture. Infrastructure spending is skewed in favour of central and western regions, from which all three leading 2016 presidential candidates come. The north, home to one-fifth of the population, has suffered not only from protracted conflict but also dire under-investment in roads, markets and electricity supply.

Following the discovery of an estimated 6.5 billion barrels of oil in the Albertine rift basin, diversification of the economy is possible. Museveni is adamant about the need for the country to build its own oil refinery to generate jobs and promote service industries. But affairs in the oil industry are as opaque as crude prices are low, and characterised by tight presidential and ministerial control, the absence of parliamentary oversight, and a paucity of contract and financial transparency in petroleum legislation.

For formal businesses, leading economic indicators are mixed. Inflation has fallen dramatically since the late 1980s. So too has the value of the national currency. In 1987, one US dollar was worth 45 Ugandan shillings; in 2016, more than 3,000 shillings. Commercial lending rates are high and savings rates low. However, Uganda will not be forced to share the pain of other African economies that over-borrowed from foreign lenders in the current economic cycle. While the currency is unlikely to arrest its long-term decline, Uganda’s debt ratio (around 30% of GDP) and its current account deficit (around 6.5% of GDP) are manageable. Ratings agencies assess the country’s outlook as “stable”.

Community service

The 1995 constitution stipulates that the state must promote equitable development, funding improvements in health care, education, sanitation and housing. The 2015/16 budget set out a 58% rise in development expenditure, to include building 293 primary schools; training 4,000 head teachers; rehabilitating nine major hospitals; building wind-powered irrigation systems in the northern district of Karamoja; and systemic improvements to service delivery. Despite regional variations caused by insecurity – or favouritism – the NRM can plausibly lay claim to important achievements since 1986.

A decade after the end of hostilities in the north, the region is home to almost half Uganda’s poor

The HIV/AIDS crisis loomed large in the NRM’s early years in power. In 1992 an estimated 18.5% of Ugandans were infected with the virus, one of the highest rates on the continent. By 2005, the figure had been reduced to just 6.4%, showing other afflicted countries what was possible with a concerted effort that combined medical awareness campaigns with consistent availability of drugs. However, the drive to improve health care has faltered. Despite a burgeoning population, total health spending averaged 9.9% of the budget between 2006 and 2013, falling short of the commitment to spend 15% on health care that Uganda made as a signatory to the 2001 Abuja Declaration. The health budget remains dependent on international donors for up to 40% of funding.

The NRM’s initial ambition for education was impressive, but achievements have been mixed. Investment has been consistent as a percentage of GDP (2–3% a year since 2000). Adult literacy improved from 56.1% in 1991 to 78.3% in 2015, with adult female literacy rising by 26.5% to exceed 70%. The NRM introduced universal primary education in 1997 and universal secondary education in 2007. This greatly increased the number of children attending primary school, from 3 to 8 million. However, drop-out rates remain the highest in East Africa. Schools are ill-equipped and overcrowded; teachers’ unions are permanently restive about conditions and pay; and the pressure on the education sector is rising inexorably due to population growth.

In 1986 the ten-point programme aimed to restore and improve social service provision in war-ravaged areas. The Luwero Triangle, an area 75km north of the capital Kampala where the bush war was most fiercely fought, continues to receive a high level of support 30 years later. The legacy of more recent war, insecurity and underdevelopment in the north has yet to be properly addressed. In Karamoja, for example, in 2010 an estimated 82% of inhabitants were living in poverty, literacy rates were just 21% and maternal mortality was double the national average.7 A decade after the end of hostilities in the north, the region is home to almost half Uganda’s poor.

The Peace, Recovery and Development Plan, launched in 2008, appeared to be a statement of intent to tackle underdevelopment in the north. So too did the appointment of the president’s wife Janet Museveni as minister for Karamoja affairs. But the shortcomings in public spending on service delivery elsewhere in the country have been replicated – and exaggerated. Roads, health centres, schools and water points have been built, but not in sufficient quantity and not to a sufficiently high standard. The functionality and sustainability of assets has been overlooked: too frequently schools and health facilities are constructed but not adequately equipped, staffed or maintained. A lack of community involvement and awareness at the design stage, and erratic distribution of funds to local administrations, are typical. Widespread deprivation and longstanding grievances remain unaddressed.

“The chair is sweet”8

Corruption is “endemic at almost every level of society” despite 30 years of promises to eliminate it.9 Although trust in the president has reportedly increased since 2012, people increasingly distrust parliament, the judiciary, state institutions and public officials. Only 26% of Ugandans feel that the government’s response to corruption is “adequate”.10 Museveni himself acknowledges that embezzlement and abuse of office are problems.

Anti-corruption measures include the Anti-Corruption Act, Enforcement of Leadership Code of Conduct Act, and the Anti-Corruption Court (ACC). Nevertheless, the independence of the judiciary and the state’s willingness to investigate the influential or affluent are questionable. An ACC judge said that his “court is tired of trying tilapias when crocodiles are left swimming”.11

Between 40% and 45% of eligible voters have never known any other leader

Politics in Uganda is monetised. In 2011 inflation soared to 18.8% compared to 4.1% in 2010, fuelled to a large extent by excessive (pre-election) government spending. The Governor of the Bank of Uganda later admitted that the administration has misled him into printing money for indirect, unspecified expenditures. Despite legal requirements to do so, the NRM made no declaration of campaign spending and allowed no audit of its campaign finances.

In the lead-up to the 2016 elections, MPs have shared US$11.1m to “consult” their constituents. Constituency visits can be very expensive, and many MPs are in debt. Cash hand-outs do not buy votes in Uganda; but a failure to spend gives voters the impression that candidates are looking for their turn “to eat”, not to serve. Indebtedness partly explains the high turnover of MPs. Parliamentary research found that 55% of MPs were not returned in 2011 after serving a term in office.

More of the same?

The difference between Uganda in 1986 and 2016 is profound. The NRM’s 2016–21 manifesto focuses on economic development, tackling corruption, and peace and security. No one can accuse the party of inconsistency in its policy pronouncements. The document is coherent and considered, but the “vision” remains no more than that for most Ugandans. The NRM needs to rediscover its boldness if it is to stay remotely relevant to ordinary Ugandans; but time is not on its side – and its leader may not allow the movement to reinvent itself in his lifetime.

In 1997 Museveni claimed that “there are now people of presidential calibre and capacity who can take over when I retire, and I shall be among the first to back them”.12 In 2001 he promised that he would retire in 2006, but in 2016 he is seeking a fifth term. Between 40% and 45% of eligible voters have never known another leader. With rumours that the president may anoint his son Muhoozi Kainerugaba as his eventual successor, and with his inner circle increasingly acting like a shadow state, Museveni resembles the African president-for-life stereotype that he was so keen to distance himself from in his 1986 book, What is Africa’s Problem?

Demography is the biggest threat to the progress made under Museveni and the NRM since 1986 – and to Uganda’s very stability. The population is one of the youngest in Africa: 75% of its 35 million citizens are under the age of 30. The formal economy annually creates 9,000 positions, but 400,000 school leavers begin searching for jobs each year. The real unemployment rate is estimated at 64%.13 Meanwhile, the laudable performance in poverty reduction over two decades is threatened. The number of “insecure non-poor” has risen sharply in the same period, from 5.8 to 14.7 million – more than 40% of the population.14

Oil resources and closer regional integration of the East African Community provide Uganda with opportunities that, if shrewdly exploited, could spur structural transformation of the economy, fund more productive development expenditure, and provide more jobs. The winner of February’s presidential election will be male, over 55, from the west of the country, and a past or present NRM grandee. That much will be no different, but young Ugandans, in particular, urgently need something more than steady progress.