On December 4th 2014, Dr Michael Walls spoke about the successes and challenges facing Somaliland’s democratic transition. The event marked the launch of Africa Research Institute’s publication: “Statebuilding in the Somali Horn: Compromise, Competition and Representation”.

Michael emphasised that his perspective of Somaliland was that of an academic and outsider, striving to be objective and to place contemporary politics in its proper historical and cultural context. The importance of understanding Somali culture and the history of the Horn of Africa was thus quickly established as a central theme of the evening’s discussion.

Disagreeing with Somali scholar Said Samatar’s pronouncement that Somalis are “addicted to congenital egalitarian anarchy”, Michael instead described Somali society as deeply democratic, albeit in a form which may not be immediately familiar to outsiders. Somali governance has historically been grounded in consensus, with adult males eligible to participate in decision-making on all key issues. Over the past two decades, Somaliland has also taken steps towards representative democracy, establishing a House of Representatives and electing local councillors. The country’s transition is less one of democratisation than from a primarily discursive form of democracy to a more representative form. This shift might be perceived as representing a diminution of democracy, as adult males are called upon to cede power to a representative between elections. Once this erosion of influence is understood, it becomes clearer why elections have proved so contentious in the Somali Horn.

Somaliland is usually the subject of two conflicting narratives. One presents the Somali Horn as a region perpetually inhospitable to the development of nation states; the other romanticises Somaliland as a home-grown success story, exhibiting a unique degree of stability, with external support notably absent. Michael contests both of these accounts. Somaliland is by no means the first functional Somali state, nor should it be thought of as an isolated arrangement borne solely out of local efforts. Over the past thousand years, there have been a series of long-lived, very successful, relatively centralised Somali states – the Adal Sultanate for example. Michael also noted that Somaliland has not been entirely ignored by the international community. Instead, in a region with a history of city-states and tribal administrations, what makes Somaliland unique is the unprecedented progress it has made in establishing a bordered nation state.

Despite Somaliland’s achievements, significant challenges still remain. Tensions in the eastern districts, forthcoming elections, the Guurti and the absence of women in representative institutions all need to be addressed. The likelihood of oil and gas discoveries in the Nugaal Valley seems to be heightening tensions.

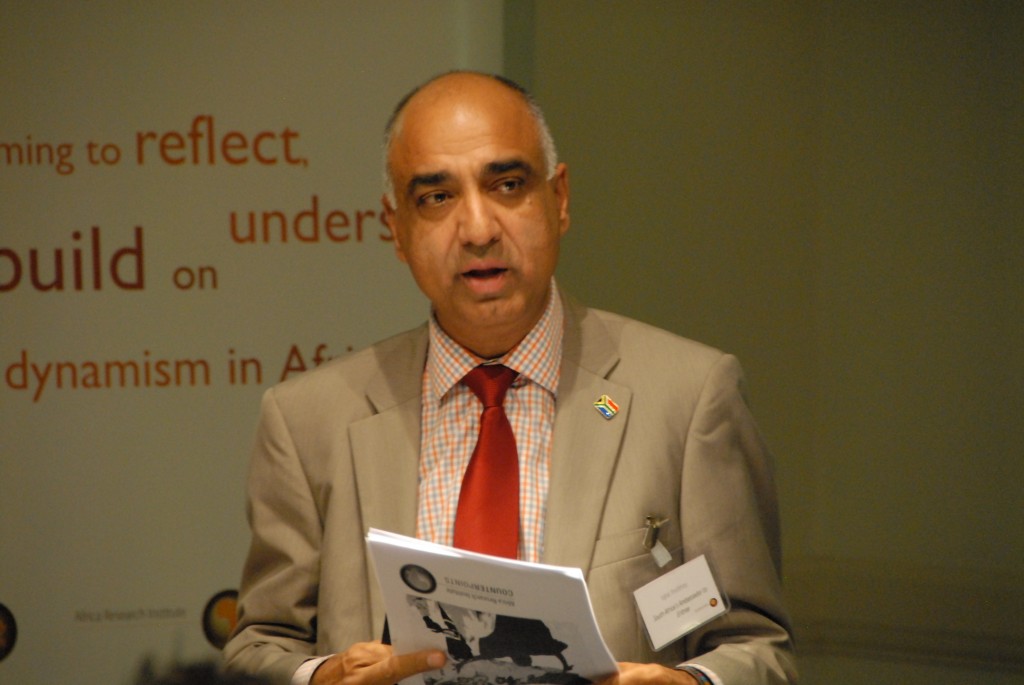

Iqbal Jhazbhay, South Africa’s Ambassador to Eritrea, responded to Michael’s presentation. With regards to the quest for international recognition, HE Jhazbhay highlighted its importance as a disciplining and galvanising force – but also pointed out that Somaliland has failed to capitalise on opportunities, despite an arguably strong case under public international law. For example, the African National Congress (ANC) responded positively to the case for recognition when Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma was South African foreign minister, but Somalilanders failed to capitalise on her support. Dlamini-Zuma is now Chair of the African Union Commission, which provides an opportunity for renewed dialogue. The importance of the formal acceptance of Somaliland by the international community should not be overstated. The ambassador was careful to stress that nation-building efforts will only be successful if they are locally-driven. Furthermore, a tacit recognition of the state of Somaliland is increasingly evident.

Questions

Q: Fred Amonya, Lyciar: Is the lesson from Somaliland that an inclusive and consultative approach to policymaking can demonstrate better results than the prescriptions of the international community?

MW is in favour of a more evolutionary approach to development in general. One of the problems with the field is that it has been “technicalised”, which explains why development professionals develop areas of expertise which are assumed to be universally applicable. Technical expertise typically overrides indigenous cultural knowledge. This relationship should be reversed, even where there is a genuine need for technical expertise, as is the case with building infrastructure.

Q: Mark Lister, Progressio: What will help Somalilander women become more active participants in a complicated and delicate political process?

MW began by stating that women play a huge role in every sector of Somali society – except for formal politics. The invisibility of women in politics is a big problem but one with a clearly identifiable cause. Uncertainty as to whether women will represent the clan of their husband or their father has continually posed a barrier to inclusion. There is no easy solution to this problem but quotas, as advocated for by women’s groups like the Nagaad Network, might help to establish formal roles for Somali women.

Q: Yacin Yusuf, Impact Minority Association: What role will clans play in the next elections?

MW responded that clan will play an important role throughout the election period and will help structure both pre- and post-results negotiations. Looking back at the 2012 elections, he thought the decision to use an open voting list was a big mistake. Having every candidate stand for themselves created an environment whereby candidates went first to their clans and second to their party for support. Resources were mobilised and voters organised along clan lines; candidates would even change party if their clan wanted them to. Closed lists, on the other hand, would have helped strengthen parties rather than further fuel clan tensions.

Amaani Hoddoon, DfE: How important is central planning to a successful Somaliland?

MW finds it difficult to see how a strong central planning government could exist in Somaliland, given past difficulties. Nation states in the Somali Horn, whatever shape they take, are likely to be darlings of free marketeers, through being home to highly deregulated markets orientated towards internal and external trade. Governments are likely to be relatively weak in this context and clans will probably continue to play a significant role in social structure, as a means of crisis management.

Audio podcast:

[audiomack src=”http://www.audiomack.com/song/africaresearch/somalilands-democratic-transition-building-a-representative-state”]Videos of speaker presentations and the Q&A session: