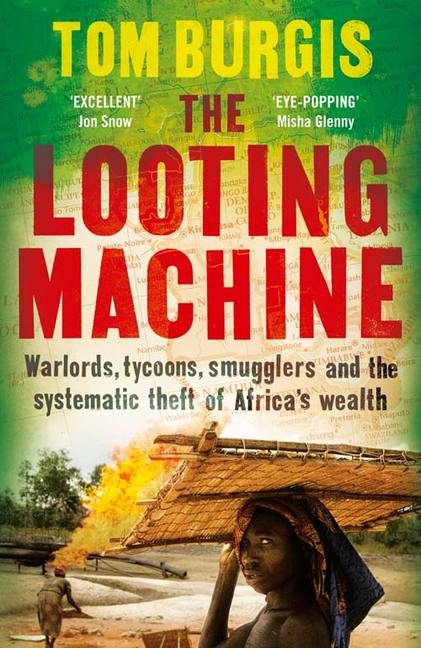

Tom Burgis is the Financial Times’ investigations correspondent, covering business, politics, corruption and conflict. He was previously the FT’s West Africa and southern Africa. His first book, The Looting Machine: Warlords, Tycoons, Smugglers and the Systematic Theft of Africa’s Wealth, uncovers the secretive networks that control Africa’s natural resources and fuel its conflicts.

Poverty in the midst of plenty: this paradox has endured in Africa from decolonisation to the era of ostensibly democratic states. At first it was explained by colonialism, then by the Cold War. Economists now call it “the resource curse”, the perverse effect of globalisation that inserts Africa’s minerals in our mobile phones and brings its oil to our petrol stations while inflicting misery and destruction on the people whose lands yield these riches.

There are plenty of suspects to blame: corrupt dictators, criminal arms dealers, cynical multinationals and unscrupulous middlemen. But is there a common thread to these iniquities? Is there a system that spans the oil banditry of Nigeria, the ravages of eastern Congo and the board rooms of South Africa’s sophisticated mining industry, enriching the few at the expense of so many?

A brilliant new book provides some answers: “The Looting Machine” by Tom Burgis, who has covered Africa for the Financial Times since 2009. In fascinating detail, the book reveals how rulers of some of Africa’s most impoverished countries channel vast natural resources through “shadow states” whose purpose is to enrich and preserve a tiny self-serving elite. The “Looting Machine” examines the secret deals between autocracies in Angola, Guinea, the DRC and Zimbabwe and their discreet business partners from Israel to China, moving prized assets to the world’s great oil and mining companies and principal financial centres at a fraction of their true value.

The book lives up to its colourful subtitle – “Warlords, tycoons, smugglers and the systematic theft of Africa’s wealth”. Showing the finesse and determination that has won him awards at the FT, and at considerable risk to his own well-being, Burgis tracks down and confronts the people at the centre of this plunder. He sees at first hand the privations, ethnic violence and state brutality suffered by the people who are governed by these predatory elites.

This is a tale not of institutions but of the people who have bypassed them in their improbable rise to power and riches. When the young Joseph Kabila was chosen to replace his assassinated father as president of the DRC, he trusted so few in power that he turned for help to a young Israeli sent abroad by his famous diamond-trading family to seek his fortune. Now Dan Gertler is the DRC’s mining kingpin, whose web of offshore companies is the link between a parallel bureaucracy and some of the world’s biggest resource companies who acquired its assets for a song. Beny Steinmetz, also an Israeli, took time off from supplying diamond-encrusted steering wheels to Formula One racing drivers to seize half of Guinea’s massive iron ore assets from mining giant Rio Tinto by offering a cut to the wife of the dying president Lansana Conté if he got the rights.

The most mysterious of these business networks was set up by Sam Pa, an obscure middleman with a few connections in Beijing who spotted the chance to forge a powerful link between official China and its largest oil supplier, Angola. Pa and officials in the Angolan state energy company created China Sonangol, a “corporate bunker within the already opaque walls of Sonangol,” as Burgis describes it.

“Through a network of obscure companies registered in Hong Kong, the Futungo (a nickname for the elite in Luanda) had plugged itself into an offshore mechanism that channelled the political power of Angola’s authoritarian rulers into the private corporate empire that Pa and his fellow founders of the Queensway Group had begun to assemble.”

Pa has never given an interview, and Burgis’s doorstep interrogation of bemused staff at Queensway’s Hong Kong head office provides one of the book’s comic moments. Elsewhere in Africa, Pa has done deals with two rulers shunned by western governments and in need of cash to suppress the opposition – Guinea’s former coup leader Captain Dadis Camara and Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. Pa’s joint venture with Zimbabwe’s secret police appears to have provided the cash for “Operation No Return”, which evicted workers from the alluvial diamond mine at Marange and turned it into the government’s big money-spinner just in time for an election campaign.

The continent’s two leading oil producers have institutionalised the looting through their state energy companies, Nigeria’s NNPC and its more efficient Angolan equivalent, Sonangol, while western companies co-operate. When Burgis revealed evidence in the FT that Sonangol had licenced a massive oil field to a local company owned by its top executive, Manuel Vicente, and two senior army officers, these officials in effect admitted that this is how business in Angola is done. Vicente, pictured smiling with arms outstretched in an interview with the author, is now the country’s vice president. The international operator of the oil block, the US-listed Cobalt International Energy, claimed it did not know who owned its local partner.

The “Looting Machine” also analyses the failure of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) in South Africa, the ANC’s key policy to redistribute the country’s wealth under majority rule. BEE has created multi-millionaires in the top ranks of the ANC who have swapped liberation credentials for a seat on the board of white-controlled companies, but left many of their black followers disillusioned. The resulting industrial unrest led to the massacre of workers by police at Lonmin’s platinum mine at Marikana.

The strength of the book is that it combines strong narrative with well-researched economic context, including the outflow of capital orchestrated by the multinationals through such practices as transfer pricing. It also cites a World Bank report on the lack of development brought by the Bretton Woods institutions’ policy of liberalising the Africa’s mining industry. This prompts a banker in Ghana to remark: “People are asking: how did the country earn nothing from a hundred years of mining?” There is also some historical perspective on contemporary plunder. As one source puts it, Sam Pa is the modern-day Cecil Rhodes.

In a world where all of us benefit from Africa’s natural wealth, the author concludes, all of us are complicit.

This review was written by ARI’s Paul Adams.

“The Looting Machine” is published by Harper Collins in the UK.